Reasoning Models Generate Societies of Thought

推理模型生成思想社会

Abstract 摘要

Large language models have achieved remarkable capabilities across domains, yet mechanisms underlying sophisticated reasoning remain elusive1, 2. Recent reasoning-reinforced models, including OpenAI’s o-series, DeepSeek-R1, and QwQ-32B, outperform comparable instruction-tuned models on complex cognitive tasks3, 4, attributed to extended test-time computation through longer chains of thought5. Here we show that enhanced reasoning emerges not from extended computation alone, but from the implicit simulation of complex, multi-agent-like interactions—a society of thought—which enables the deliberate diversification and debate among internal cognitive perspectives characterized by distinct personality traits and domain expertise. Through quantitative analysis using classified outputs and mechanistic interpretability methods applied to reasoning traces6, 7, we find that reasoning models like DeepSeek-R1 and QwQ-32B exhibit much greater perspective diversity than baseline and merely instruction-tuned models, activating broader conflict between heterogeneous personality- and expertise-related features during reasoning. This multi-agent structure manifests in conversational behaviours including question-answering sequences, perspective shifts, and reconciliation of conflicting views, as well as in socio-emotional roles that characterize sharp back-and-forth conversation, which together account for the accuracy advantage in reasoning tasks through both direct and indirect facilitation of cognitive strategies8, 9. Controlled reinforcement learning experiments further reveal that base models spontaneously increase conversational behaviours when solely rewarded for reasoning accuracy, and fine-tuning models with conversational scaffolding substantially accelerates reasoning improvement compared to base models and models fine-tuned with monologue-like reasoning. These findings indicate that the social organization of thought enables effective exploration of solution spaces. We suggest that reasoning models establish a computational parallel to collective intelligence in human groups10, 11, 12, where diversity enables superior problem-solving when systematically structured and suggest new opportunities for agent organization to harness the wisdom of crowds.

大型语言模型在各个领域取得了显著的成就,然而复杂推理背后的机制仍然难以捉摸 1, 2 。最近的推理强化模型,包括 OpenAI 的 o 系列、DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B,在复杂认知任务上优于同等指令调优模型 3, 4 ,这归因于通过更长的思维链延长了测试时的计算 5 。在这里我们表明,增强的推理并非仅来自计算的延长,而是来自对复杂、类似多智能体交互的隐式模拟——一个思想社会,它使得具有不同人格特质和领域专业知识的内部认知视角之间能够进行有意识的多样化和辩论。通过使用分类输出和应用于推理轨迹的机制可解释方法进行定量分析 6, 7 ,我们发现 DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B 等推理模型比基线和仅指令调优模型表现出更大的视角多样性,在推理过程中激活了异质人格和专业知识相关特征之间更广泛的冲突。 这种多智能体结构体现在对话行为中,包括问答序列、视角转换以及冲突观点的调和,同时也体现在社会情感角色中,这些角色以尖锐的来回对话为特征,共同通过直接和间接的认知策略促进,解释了推理任务中的准确性优势 8, 9 。受控的强化学习实验进一步揭示,基础模型在仅因推理准确性而受到奖励时,会自发地增加对话行为,而带有对话脚手架的微调模型与基础模型以及进行类似独白式推理微调的模型相比,能显著加速推理能力的提升。这些发现表明,思想的社交组织能够有效探索解决方案空间。我们建议推理模型建立与人类群体集体智能的计算平行关系 10, 11, 12 ,其中多样性在系统结构化时能够实现优越的问题解决能力,并为智能体组织利用群体智慧提供了新的机遇。

Corresponding author: James Evans (jamesaevans@google.com; jevans@uchicago.edu)

通讯作者:詹姆斯·埃文斯 (jamesaevans@google.com; jevans@uchicago.edu)

Work done as a student researcher at Google

作为谷歌学生研究员完成的工作

Artificial intelligence (AI) systems have undergone a remarkable transformation in recent years, with large language models (LLMs) demonstrating increasingly sophisticated abilities across domains, from mathematics and code to scientific and creative writing to critical decision support1, 2. Nevertheless, a persistent challenge has been the development of robust reasoning capabilities—the ability to methodically analyze problems, consider alternatives, detect errors, and arrive at reliable conclusions. Recent reasoning models, such as DeepSeek-R1, QwQ, and OpenAI’s o-series models (o1, o3, o4), are trained by reinforcement learning to “think” before they respond, generating lengthy “chains of thought”. This led to substantial improvement in reasoning accuracy compared to existing instruction-tuned language models (e.g., DeepSeek-V3, Qwen-2.5, GPT-4.1)3, 4. Yet, the character of “thinking” within reasoning models that drives success remains underexplored.

近年来,人工智能(AI)系统经历了显著变革,大型语言模型(LLMs)在数学、代码、科学和创意写作以及关键决策支持等领域展现出日益复杂的能力 1, 2 。然而,一个持续的挑战是发展强大的推理能力——即系统性地分析问题、考虑替代方案、检测错误并得出可靠结论的能力。最近的推理模型,如 DeepSeek-R1、QwQ 和 OpenAI 的 o 系列模型(o1、o3、o4),通过强化学习被训练在回应前“思考”,生成冗长的“思维链”。与现有的指令微调语言模型(例如,DeepSeek-V3、Qwen-2.5、GPT-4.1)相比,这显著提高了推理准确性 3, 4 。然而,驱动推理模型成功的“思考”特性仍待深入探索。

We propose that reasoning models learn to emulate social, multi-agent-like dialogue between multiple perspectives—what we term a “society of thought”—to improve their reasoning, given the centrality of social interaction to the development of reason in both cognitive and social scientific accounts. Mercier and Sperber’s “Enigma of Reason” argument posits that human reasoning evolved primarily as a social process, with knowledge emerging through adversarial reasoning and engagement across differing viewpoints10. Empirical work supports the idea that groups outperform individuals on a wide range of reasoning tasks by pooling information, calibrating confidence, and exhibiting collective intelligence through balanced turn-taking among diverse perspectives13, 14, 12, 15. Cognitive diversity, stemming from variation in expertise and personality traits, enhances problem solving, particularly when accompanied by authentic dissent16, 17, 18, 19, 11, 20, 21, 22. Together, these findings suggest that robust reasoning emerges through interaction and the integration of diverse perspectives, and that key reasoning strategies, including verification and backtracking, may be realized through the conversation of simulated personas.

我们提出,推理模型通过学习模拟多视角之间的社会性、多智能体式对话——我们称之为“思想社会”——来提升其推理能力,鉴于社会互动在认知和社会科学理论中对理性发展的核心作用。Mercier 和 Sperber 的《理性的谜题》论证认为,人类推理主要是作为一种社会过程进化而来的,知识通过不同观点间的对抗性推理和参与而涌现 10 。实证研究支持这样一种观点:通过汇集信息、校准信心,并在不同视角间通过平衡的轮流发言展现出集体智能,群体在广泛的推理任务上优于个体 13, 14, 12, 15 。认知多样性,源于专业知识和性格特征的差异,能够提升问题解决能力,尤其是在伴随着真诚的异议时 16, 17, 18, 19, 11, 20, 21, 22 。 这些发现共同表明,强大的推理能力是通过互动和不同观点的整合而出现的,而关键的推理策略,包括验证和回溯,可能可以通过模拟角色的对话来实现。

While diversity and debate contribute directly to collective intelligence, many theories further suggest that individuals reason better when they simulate this capacity. A single, self-centered perspective can lead to systematic biases in reasoning; if individuals effectively simulate multiple, self-distanced perspectives with their minds, as in dialectical thinking, this can reduce decision biases within them23, 24, 25. The “social brain hypothesis” suggests that higher-order intelligence primarily evolved to meet the cognitive demands of processing and simulating social interactions26, 27. Individuals who simulate others’ differing perspectives through improved “theory-of-mind” capabilities enhance collective team performance18. Furthermore, theorists have argued that individual reason itself emerged from a simulation of collective discourse. Bakhtin’s notion of the “dialogic self” and Cooley and Mead’s theory of the “looking glass self” argue that human thought itself takes the form of an internalized conversation among multiple perspectives28, 29, 30, Mead2022-rw. Even in the history of artificial intelligence, Minsky conceptualized intelligence as an emergent property of interacting cognitive agents, or a “Society of Mind”31.

虽然多样性和辩论直接有助于集体智慧,但许多理论进一步指出,当个体模拟这种能力时,他们的推理能力会更好。单一的自我中心视角会导致推理中的系统性偏差;如果个体通过心灵有效地模拟多个、自我疏离的视角,就像辩证思维那样,这可以减少他们决策中的偏差 23, 24, 25 。 “社会大脑假说”认为,高级智慧主要进化是为了满足处理和模拟社会互动的认知需求 26, 27 。通过改进“心智理论”能力来模拟他人不同视角的个体,可以增强集体团队的表现 18 。此外,理论家们认为,个体推理本身是从集体话语的模拟中产生的。巴赫金关于“对话自我”的概念以及库利和米德的“镜像自我”理论都认为,人类思维本身就呈现出多重视角内部化对话的形式 28, 29, 30, Mead2022-rw 。 即使在人工智能的历史中,明斯基也将智能概念化为交互认知主体的涌现属性,或是一个“心智社会” 31 。

Therefore, whether AI systems directly simulate multi-agent discourse or simulate minds that, in turn, simulate multi-agent discourse, we propose that reasoning models like DeepSeek-R1 improve reasoning via “society of thought”—implicit simulations of multi-agent-like interactions between diverse perspectives that give rise to them. We use the term to denote text generation that simulates social exchange among multiple perspectives to increase the collective diversity of ideas through conversational roles that put them in competition. Without deploying separate models prompted to interact with one another32, 33, 34, we suggest that behaviourally similar conversations between diverse perspectives occur and are leveraged within reasoning models.

因此,无论是人工智能系统直接模拟多主体对话,还是模拟那些反过来模拟多主体对话的心灵,我们都提出推理模型(如 DeepSeek-R1)通过“思想社会”——即不同视角之间产生互动的隐式模拟——来提升推理能力。我们使用这一术语来指代模拟多重视角之间社会交流的文本生成,通过对话角色将它们置于竞争状态,从而增加思想的集体多样性。在不部署分别提示以相互交互的模型 32, 33, 34 的情况下,我们建议不同视角之间的行为相似对话会发生,并在推理模型中被利用。

Reasoning models like DeepSeek-R1 develop reasoning abilities through reinforcement learning, which iteratively compensates reasoning behaviour that yields correct answers. Following these performance improvements, debates have naturally arisen about what kinds of behaviours contribute to better reasoning performance. While earlier studies focus on how the model learns to scale test-time computations and generate longer reasoning traces35, 2, merely increasing trace length does not account for the observed improvements in reasoning capabilities. This suggests that qualitative changes in reasoning structure matter more than quantitative scaling alone36, 35, 37. Recent analyses pinpoint behavioural patterns that improve reasoning accuracy, such as verification of earlier assumptions, backtracking, and exploration of alternatives4, 8, 36, 35, 37. Mechanistic interpretability research has shown that features in language models such as the frequent use of words like “wait,” “but,” and “however”—are associated with these behaviours38, 39, 40, 41. The characteristics of these features, however, such as their prevalence in social and conversational settings, have rarely been explored. Research in other contexts has suggested that the simulation of multi-agent conversations can boost accuracy and divergent thinking in LLMs42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 34, 47. While LLMs can exhibit cognitive biases that hinder reasoning, the simulation of interaction between different perspectives could mitigate biases when verified through checks and balances48, 34, 49. This leads us to hypothesize that reinforcement learning may systematically select and reward behaviour patterns that resemble multi-agent interactions within reasoning models, and these simulated interactions enable models to reason effectively.

深度推理模型如 DeepSeek-R1 通过强化学习发展推理能力,该过程通过迭代补偿产生正确答案的推理行为。在性能提升之后,自然产生了关于哪些行为有助于提升推理性能的讨论。早期研究主要关注模型如何学习扩展测试时的计算并生成更长的推理轨迹 35, 2 ,但仅仅增加轨迹长度并不能解释推理能力的提升。这表明推理结构的定性变化比单纯的定量扩展更为重要 36, 35, 37 。最近的分析指出了提升推理准确性的行为模式,例如验证早期假设、回溯和探索替代方案 4, 8, 36, 35, 37 。机制可解释性研究显示,语言模型中的某些特征,如频繁使用“wait”、“but”和“however”等词语——与这些行为相关 38, 39, 40, 41 。然而,这些特征的特性,如它们在社会和对话环境中的普遍性,却很少被探索。 其他领域的研究表明,模拟多智能体对话可以提高 LLMs 的准确性和发散性思维 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 34, 47 。虽然 LLMs 可能表现出阻碍推理的认知偏差,但通过制衡机制验证的不同视角之间的交互模拟可以减轻这些偏差 48, 34, 49 。这使我们假设,强化学习可能会系统地选择和奖励在推理模型中类似于多智能体交互的行为模式,而这些模拟交互使模型能够有效推理。

Here we investigate the prevalence of reasoning traces of DeepSeek-R1, as well as QwQ-32B, that mimic simulated social interactions, quantifying how conversational behaviours, socio-emotional roles, and diversity of implicit agent “perspectives” contribute to reasoning performance. We first identify whether conversational behaviours and socio-emotional roles—hallmarks of human dialogue such as questioning, perspective taking, and reconciliation—are present in DeepSeek-R1’s and QwQ-32B’s reasoning traces. Then we test whether conversational behaviour contributes to reasoning performance. Based on the mechanistic interpretability method applied to DeepSeek-R1’s distilled model (DeepSeek-R1-Llama-8B), we find that steering features associated with a discourse marker, such as expressing surprise in conversational contexts, improves reasoning accuracy both directly and indirectly through the facilitation of cognitive strategies.

在这里,我们研究了 DeepSeek-R1 以及模仿模拟社交互动的 QwQ-32B 的推理痕迹的普遍性,量化了对话行为、社会情感角色以及隐式代理“视角”的多样性如何对推理性能做出贡献。我们首先识别 DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B 的推理痕迹中是否存在对话行为和社会情感角色——这些是人类对话的标志,如提问、视角转换和和解。然后我们测试对话行为是否有助于推理性能。基于应用于 DeepSeek-R1 蒸馏模型(DeepSeek-R1-Llama-8B)的机制可解释性方法,我们发现与话语标记相关的引导特征,例如在对话环境中表达惊讶,能够直接和间接地通过促进认知策略来提高推理准确性。

Next, we analyze the diversity of reasoning “perspectives” or simulated voices within DeepSeek-R1’s and QwQ-32B’s reasoning traces. Literature suggests that LLM reasoning can fail if models do not engage in meaningful disagreement and instead conform to misleading initial claims through pleasant, “sycophantic” conversations that propagate incorrect assumptions and knowledge49, 50, 51. Successful reasoning models may therefore exhibit disagreement driven by diversity in simulated perspectives, expressed through distinct personalities and expertise to avoid the “echo chamber” that leads to wrong answers. Therefore, we analyze reasoning traces using LLM-as-judge to accurately identify distinct voices underlying conversation. We find that DeepSeek-R1 and QwQ-32B display much greater personality and expertise diversity than non-reasoning models within their reasoning traces, presumably to maximize the benefits of multi-agent-like interaction through diversification. We further find that steering a conversational feature in a model’s activation space leads to the activation of a more diverse range of personality- and expertise-related features.

接下来,我们分析 DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B 推理轨迹中推理“视角”或模拟声音的多样性。文献表明,如果模型不进行有意义的分歧,而是通过令人愉悦的、“阿谀奉承”式的对话,使推理过程符合误导性的初始主张,从而传播错误的假设和知识,那么 LLM 的推理可能会失败 49, 50, 51 。因此,成功的推理模型可能会表现出由模拟视角多样性驱动的分歧,通过不同的个性和专业知识来表达,以避免导致错误答案的“回声室”。为此,我们使用 LLM 作为评判者来分析推理轨迹,以准确识别对话背后不同的声音。我们发现,DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B 在其推理轨迹中表现出比非推理模型大得多的个性和专业知识多样性,这可能是为了通过多样化来最大化类似多智能体交互的收益。我们进一步发现,引导模型激活空间中的对话特征会导致激活更多与个性和专业知识相关的特征。

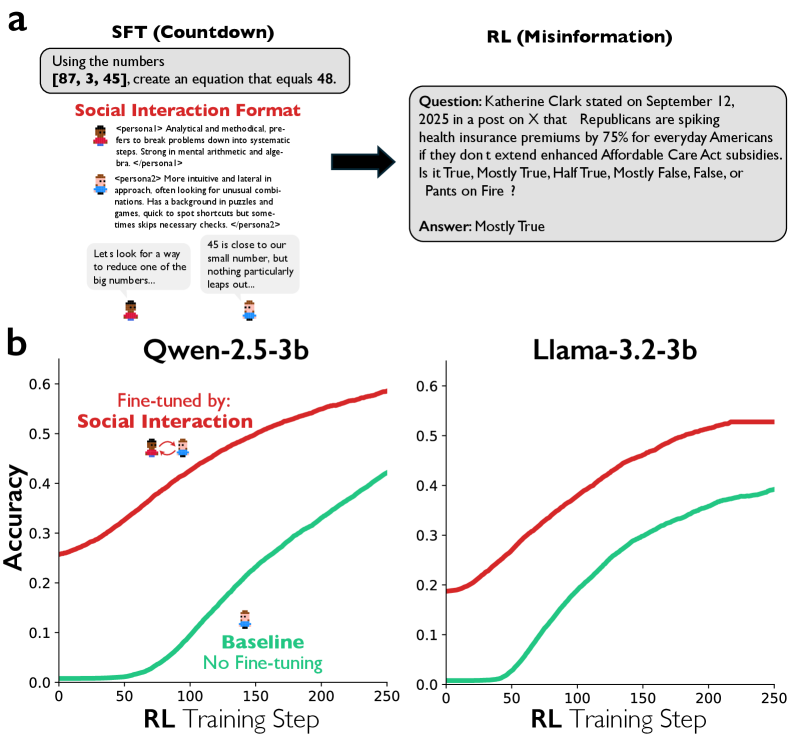

Finally, we conduct a controlled reinforcement learning experiment to examine the role of conversational behaviours. We focus on self-taught reinforcement learning that rewards only accuracy and correct formatting (i.e., wrapping the thinking process between <think> and </think>), the common approach for improving modern language models’ reasoning capabilities4. Based on a symbolic arithmetic task (Countdown game)8, 52, as well as a misinformation identification task, we apply reinforcement learning that rewards reasoning traces leading to accurate answers on open-source LLMs. Interestingly, experiments reveal that the base model can spontaneously develop conversational behaviours—such as self-questioning and perspective shifts—when rewarded solely for reasoning accuracy, without any explicit training signal for dialogue structure. Moreover, following methods of prior ablation research8, we observe that initially fine-tuning these models for conversational structure leads to faster accuracy improvements, outperforming both their baseline counterparts and models fine-tuned with “monologue-like” reasoning, particularly during the early stages of training in two distinct model systems (Qwen-2.5-3B and Llama-3.2-3B). These results suggest that conversational scaffolding facilitates the discovery and refinement of reasoning strategies during reinforcement learning.

最后,我们进行了一项受控的强化学习实验,以检验对话行为的作用。我们专注于自我教学的强化学习,该学习方法仅奖励准确性和正确的格式(即在和之间包裹思考过程),这是提高现代语言模型推理能力的一种常见方法 4 。基于一个符号算术任务(倒计时游戏) 8, 52 ,以及一个虚假信息识别任务,我们在开源 LLMs 上应用了强化学习,该方法奖励能够得出准确答案的推理轨迹。有趣的是,实验表明,当仅奖励推理准确性时,基础模型可以自发地发展对话行为——例如自我提问和视角转换——而没有任何关于对话结构的显式训练信号。 此外,遵循先前消融研究的方法 8 ,我们观察到,最初针对对话结构微调这些模型能够更快地提高准确率,其表现优于基线模型以及使用“独白式”推理进行微调的模型,特别是在两个不同模型系统(Qwen-2.5-3B 和 Llama-3.2-3B)训练的早期阶段。这些结果表明,对话式支架在强化学习过程中有助于发现和优化推理策略。

Results 结果

We compile a suite of widely used benchmarks used in prior research and official model cards of reasoning models (BigBench Hard, GPQA, MATH (Hard), MMLU-Pro, MUSR, and IFEval)3, 4, spanning symbolic logic, mathematical problem solving, scientific reasoning, multi-agent inference, and instruction following tasks (see Methods: Data). From this pool, we sample 8,262 problems and generate reasoning traces using DeepSeek-R1-0528 (671B parameters; hereafter DeepSeek-R1) and QwQ-32B. For comparison, we also generate reasoning traces using conventional, instruction-tuned models of varying sizes: DeepSeek-V3-0324 (671B parameters; hereafter DeepSeek-V3), Qwen-2.5-32B-Instruct (hereafter Qwen-2.5-32B-IT; the instruction-tuned model based on Qwen-2.5-32B from which QwQ-32B is derived), Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct (hereafter Llama-3.3-70B-IT), and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct (hereafter Llama-3.1-8B-IT)53, 54. DeepSeek-V3 is the instruction-tuned model based on DeepSeek-V3-base from which DeepSeek-R1 is derived, and Qwen-2.5-32B-IT is the instruction-tuned model based on Qwen-2.5-32B from which QwQ-32B is derived (see Methods: Data)53, 54.

我们收集了先前研究中广泛使用的推理模型基准测试套件和官方模型卡(BigBench Hard、GPQA、MATH(Hard)、MMLU-Pro、MUSR 和 IFEval) 3, 4 ,涵盖符号逻辑、数学问题解决、科学推理、多智能体推理和指令跟随任务(参见方法:数据)。从这些基准测试中,我们抽取了 8,262 个问题,并使用 DeepSeek-R1-0528(671B 参数;以下简称 DeepSeek-R1)和 QwQ-32B 生成推理轨迹。为了比较,我们还使用不同规模的常规指令微调模型生成了推理轨迹:DeepSeek-V3-0324(671B 参数;以下简称 DeepSeek-V3)、Qwen-2.5-32B-Instruct(以下简称 Qwen-2.5-32B-IT;基于 Qwen-2.5-32B 的指令微调模型,QwQ-32B 即由此衍生)、Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct(以下简称 Llama-3.3-70B-IT)和 Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct(以下简称 Llama-3.1-8B-IT) 53, 54 。DeepSeek-V3 是基于 DeepSeek-V3-base 的指令微调模型,而 DeepSeek-R1 即由此衍生;Qwen-2.5-32B-IT 是基于 Qwen-2.5-32B 的指令微调模型,而 QwQ-32B 即由此衍生(参见方法:数据) 53, 54 。

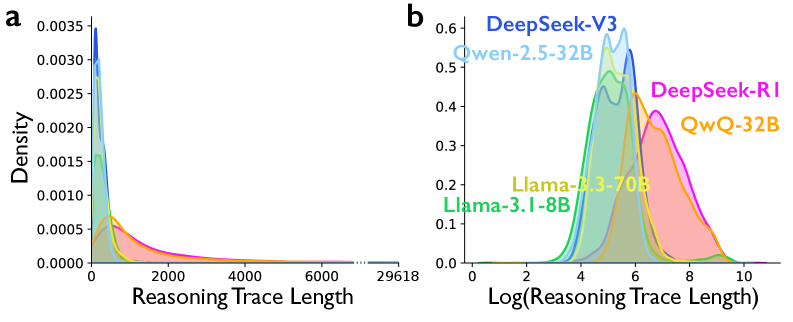

Next, we estimate behavioural differences between reasoning models (DeepSeek-R1 and QwQ-32B) and the instruction-tuned models. We use linear probability models with problem-level fixed effects, which control for all task-specific characteristics, such as the difficulty of tasks. Specifically, we compare each reasoning model with its corresponding instruction-tuned counterpart (i.e., DeepSeek-R1 vs. DeepSeek-V3; QwQ-32B vs. Qwen-2.5-3B-IT) on the presence of conversational behaviours and socio-emotional roles. We control for log-transformed reasoning trace length (Extended Data Fig. 1) to consider that observed differences are not merely driven by “longer” chains of thought—that is, we demonstrate that reasoning models exhibit more frequent conversational behaviours and socio-emotional roles even when trace lengths are similar (see Methods: Statistical analyses).

接下来,我们估计推理模型(DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B)与指令微调模型之间的行为差异。我们使用带有问题级固定效应的线性概率模型,该模型控制所有与任务相关的特征,例如任务的难度。具体来说,我们将每个推理模型与其对应的指令微调模型进行比较(即 DeepSeek-R1 与 DeepSeek-V3;QwQ-32B 与 Qwen-2.5-3B-IT),比较它们在对话行为和社会情感角色方面的表现。我们控制了对推理轨迹长度进行对数转换的变量(扩展数据图 1),以考虑观察到的差异并非仅仅由“更长的”思维链驱动——也就是说,我们证明即使轨迹长度相似,推理模型也表现出更频繁的对话行为和社会情感角色(参见方法:统计分析)。

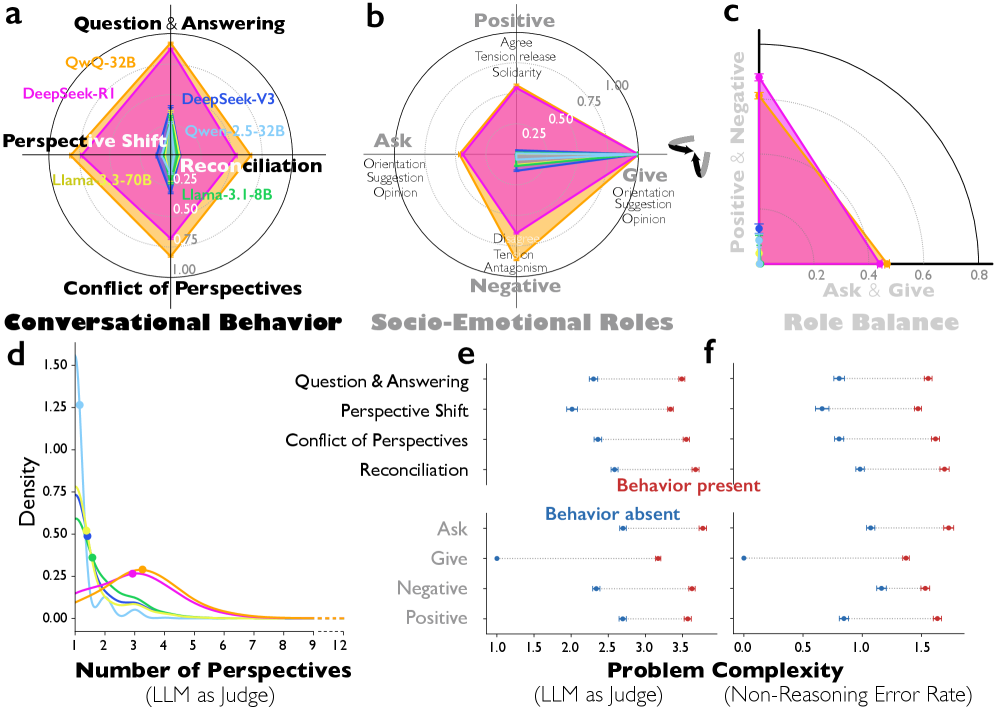

图 1:思维链推理中的对话行为和 Bales 的社会情感角色。a,包含每种对话行为(问题回答、视角转换、视角冲突和和解)的推理轨迹比例。b,推理轨迹中表达的 Bales 的十二个社会情感角色比例,分为四个高级类别:询问与提供信息,以及积极与消极情感角色(所有十二个角色的定义见补充数据图 3)。c,测量每个社会情感角色对的 Jaccard 指数,定义为同时包含两个角色的推理轨迹数量除以包含任一角色的推理轨迹数量(即询问与提供;积极与消极)。d,使用 LLM 作为评判者识别的推理轨迹中不同视角数量的分布。e,DeepSeek-R1 中对话行为和高级社会情感角色的存在导致的问题复杂度差异,使用 LLM 作为评判者,在七点李克特量表上测量(1=极其简单;7=极其困难)。 点表示在行为或角色存在(红色)或不存在(蓝色)的轨迹中的平均复杂性。f,DeepSeek-R1 中由对话行为和社会情感角色的存在导致的问题复杂性差异,通过在相同问题上的指令调优(非推理)模型的错误率来衡量(参见方法:测量)。误差线表示 95%置信区间。

Conversational Behaviours and Socio-Emotional Roles

对话行为与社会情感角色

We begin by investigating whether conversational behaviours and socio-emotional roles constitutive of back-and-forth dialogue are prevalent in reasoning traces. Using an LLM-as-judge, we quantify the occurrence of four conversational behaviours—defined as behaviours signaling the simulation of exchanges among multiple perspectives to explore a given problem—within each reasoning trace: (1) question–answering, in which the trace poses and then resolves questions; (2) perspective shifts, where alternative viewpoints are explored; (3) conflicts of perspectives, in which competing viewpoints are sharply contrasted; and (4) reconciliation, where conflicting viewpoints are integrated and coherently resolved.

我们首先调查在推理痕迹中,构成来回对话的对话行为和社会情感角色是否普遍存在。使用 LLM 作为评判者,我们量化了在每个推理痕迹中四种对话行为的发生情况——这些行为被定义为通过模拟多方视角来探讨给定问题的交互行为:(1) 问答,其中痕迹提出并解决问题;(2) 视角转换,探索不同的观点;(3) 视角冲突,其中竞争性观点被鲜明对比;(4) 调和,其中冲突性观点被整合并连贯解决。

We also examine socio-emotional roles based on Bales’ Interaction Process Analysis (IPA)55. This identifies 12 interaction roles grouped into four categories: (1) asking for orientation, opinion, and suggestion, (2) giving orientation, opinion, and suggestion, (3) negative emotional roles (disagreement, antagonism, tension), and (4) positive emotional roles (agreement, solidarity, tension release), which together characterize interactive group activity. These behaviours are annotated using an LLM-as-judge (Gemini-2.5-Pro) that shows substantial agreement with both a human rater (average ICC(3,1) = .756) and another LLM (GPT-5.2; average ICC(3,1) = .875) (see Methods: Measurements and Supplementary Method: LLM-as-judge prompts (Conversational behaviours and Socioemotional roles)).

我们还基于巴尔斯的互动过程分析(IPA) 55 检查社会情感角色。这识别出 12 种互动角色,分为四类:(1)寻求方向、观点和建议,(2)提供方向、观点和建议,(3)负面情感角色(不同意、对抗、紧张),以及(4)正面情感角色(同意、团结、紧张释放),这些共同描述了互动小组活动。这些行为使用 LLM 作为裁判(Gemini-2.5-Pro)进行标注,该裁判与人类裁判(平均 ICC(3,1) = .756)和另一个 LLM(GPT-5.2;平均 ICC(3,1) = .875)显示出高度一致性(参见方法:测量和补充方法:LLM 作为裁判的提示(对话行为和社会情感角色))。

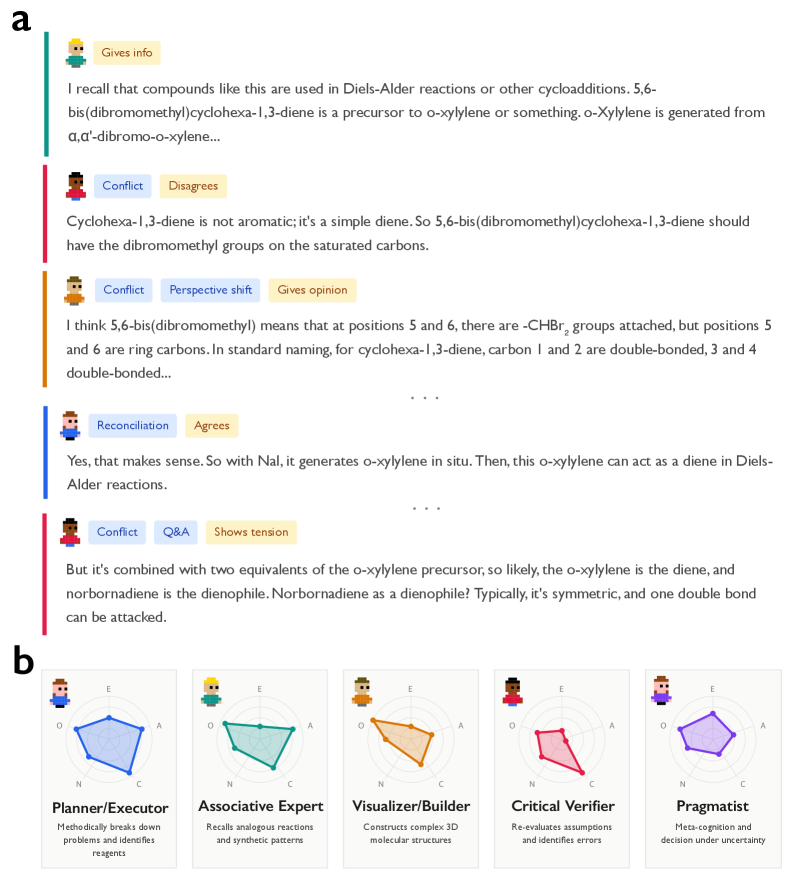

To illustrate how reasoning traces are annotated, we provide examples in Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Methods: Annotation Examples. In an organic chemistry problem requiring multi-step reaction analysis to identify the final product’s structure (i.e., multi-step Diels-Alder synthesis), DeepSeek-R1 exhibits perspective shifts and conflict, expressed through socio-emotional roles such as disagreement, giving opinion, and giving orientation (e.g., “But here, it’s cyclohexa-1,3-diene, not benzene.” “Another possibility: the high heat might cause the ketone to lose CO or something, but unlikely.”). In contrast, DeepSeek-V3’s trace on the same problem shows no conflict of perspectives, no perspective shifts, and no disagreement—only giving opinions and orientations in a monologic sequence without self-correction, concluding with “8 is a reasonable estimate”, the wrong answer, as a consequence of incomplete reasoning. In a creative sentence rewriting task, DeepSeek-R1 debates competing stylistic proposals through conflict of perspectives, as well as socio-emotional roles such as disagreement and giving suggestion: “But that adds ‘deep-seated’ which wasn’t in the original. We should avoid adding new ideas.” “Wait, that’s not a word.” “But note: ‘cast’ can be less forceful than ‘flung’. So let’s use ‘hurled’.” DeepSeek-V3, by contrast, shows minimal conflict and no disagreement, producing suggestions without the iterative refinement observed in DeepSeek-R1.

为了说明推理轨迹是如何标注的,我们在扩展数据图 2 和补充方法:标注示例中提供了示例。在一个需要多步反应分析以确定最终产物结构的有机化学问题(即多步 Diels-Alder 合成)中,DeepSeek-R1 表现出视角转换和冲突,通过诸如不同意、给出观点和给出方向等社会情感角色来表达(例如,“但这里,它是环己-1,3-二烯,不是苯。” “另一种可能性:高温可能导致酮失去 CO 或什么,但不太可能。”)。相比之下,DeepSeek-V3 在同一问题上的轨迹没有视角冲突,没有视角转换,也没有不同意——仅以单话语序给出观点和方向,没有自我纠正,最终得出“8 是一个合理的估计”,这是一个错误的答案,这是由于推理不完整所致。在一个创造性句子改写任务中,DeepSeek-R1 通过视角冲突以及诸如不同意和给出建议等社会情感角色来辩论竞争性的风格提案:“但那增加了‘根深蒂固’,而原文中并没有。” 我们应该避免添加新想法。” “等等,这不是一个词。” “但是请注意:'cast'可能比'flung'更不强烈。所以让我们用'hurled'。”相比之下,DeepSeek-V3 显示出极少的冲突,没有分歧,产生建议而没有 DeepSeek-R1 中观察到的迭代改进。

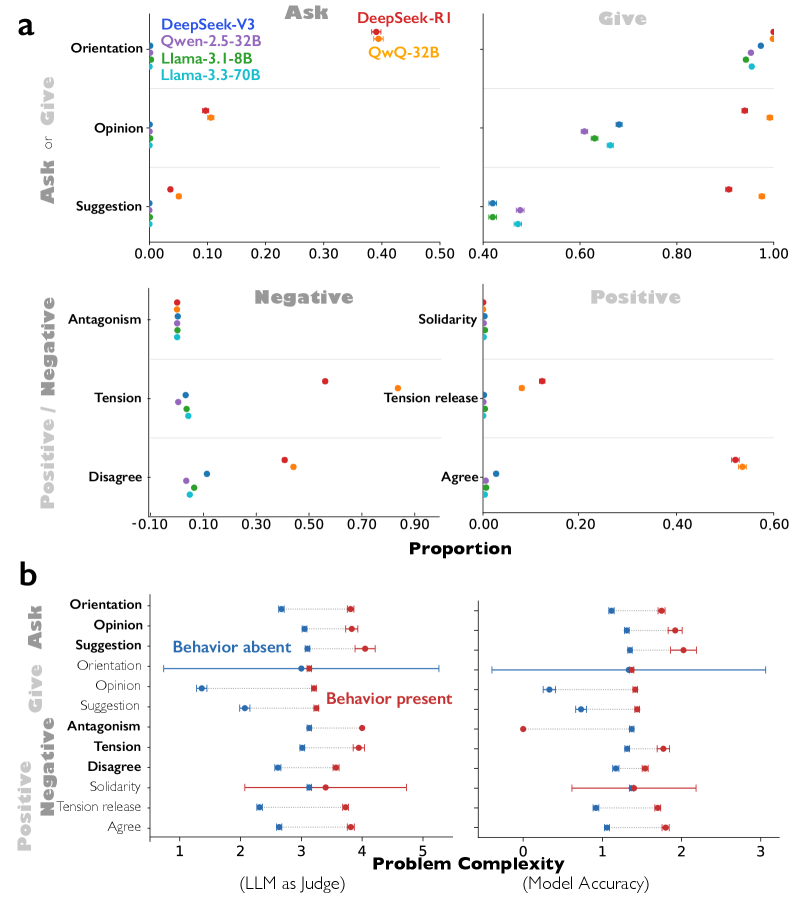

As shown in Fig. 1a, we quantify the occurrence of four conversational behaviours within each reasoning trace, and report the proportion of traces exhibiting more than one such behaviour. DeepSeek-R1 and QwQ-32B exhibit conversational behaviours far more frequently than instruction-tuned models. DeepSeek-R1 shows significantly more question–answering ( = 0.345, 95% CI = [0.328, 0.361], t(8261) = 41.64, p < 110-323), perspective shifts ( = 0.213, 95% CI = [0.197, 0.230], t(8261) = 25.55, p < 110-137), and reconciliation ( = 0.191, 95% CI = [0.176, 0.207], t(8261) = 24.31, p < 110-125) compared to DeepSeek-V3. QwQ-32B displays a similar pattern relative to Qwen-2.5-32B-IT, with greater question–answering ( = 0.459, 95% CI = [0.444, 0.475], t(8261) = 57.57, p < 110-323), perspective shifts ( = 0.378, 95% CI = [0.362, 0.394], t(8261) = 46.92, p < 110-323), conflicts of perspectives ( = 0.293, 95% CI = [0.277, 0.308], t(8261) = 37.08, p < 110-277), and reconciliation ( = 0.344, 95% CI = [0.328, 0.360], t(8261) = 42.59, p < 110-323). Notably, all instruction-tuned models show consistently low prevalence of conversational behaviours regardless of parameter count (8B, 32B, 70B, 671B).

如图 1a 所示,我们量化了每个推理轨迹中四种对话行为的发生情况,并报告了表现出一种以上这些行为的轨迹比例。DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B 表现出对话行为的频率远高于指令微调模型。与 DeepSeek-V3 相比,DeepSeek-R1 表现出显著更多的问答行为( = 0.345, 95% CI = [0.328, 0.361], t(8261) = 41.64, p < 1 10 -323 )、视角转换( = 0.213, 95% CI = [0.197, 0.230], t(8261) = 25.55, p < 1 10 -137 )和和解行为( = 0.191, 95% CI = [0.176, 0.207], t(8261) = 24.31, p < 1 10 -125 )。QwQ-32B 相对于 Qwen-2.5-32B-IT 表现出类似的模式,具有更高的问答行为( = 0.459, 95% CI = [0.444, 0.475], t(8261) = 57.57, p < 1 10 -323 )、视角转换( = 0.378, 95% CI = [0.362, 0.394], t(8261) = 46.92, p < 1 10 -323 )、视角冲突( = 0.293, 95% CI = [0.277, 0.308], t(8261) = 37.08, p < 1 10 -277 )和和解行为( = 0.344, 95% CI = [0.328, 0.360], t(8261) = 42.59, p < 1 10 -323 )。 值得注意的是,所有经过指令微调的模型,无论参数数量(8B、32B、70B、671B)如何,都表现出对话行为的低发生率。

As shown in Fig. 1b, both DeepSeek-R1 and QwQ-32B exhibit more reciprocal socio-emotional roles compared to their instruction-tuned counterparts: they both ask for and give orientations, opinions, and suggestions, while also displaying both negative and positive roles. DeepSeek-R1 asks more frequently than DeepSeek-V3 ( = 0.189, 95% CI = [0.176, 0.203], t(8261) = 27.47, p < 110-158), engages more in negative roles ( = 0.162, 95% CI = [0.147, 0.176], t(8261) = 21.87, p < 110-10), and displays more positive roles ( = 0.278, 95% CI = [0.263, 0.293], t(8261) = 35.38, p < 110-254). QwQ-32B shows a similar pattern relative to Qwen-2.5-32B-IT, with increased asking ( = 0.200, 95% CI = [0.186, 0.215], t(8261) = 27.21, p < 110-155), negative roles ( = 0.450, 95% CI = [0.436, 0.463], t(8261) = 64.77, p < 110-323), and positive roles ( = 0.312, 95% CI = [0.296, 0.327], t(8261) = 39.17, p < 110-307). In contrast, instruction-tuned models predominantly give orientations, opinions, and suggestions without reciprocal asking behaviours or emotional engagement, producing one-sided monologues rather than simulated dialogue.

如图 1b 所示,与指令微调的模型相比,DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B 表现出更多的互惠社会情感角色:它们都请求和提供指导、观点和建议,同时也展现出负面和正面的角色。DeepSeek-R1 的请求频率高于 DeepSeek-V3 ( = 0.189, 95% CI = [0.176, 0.203], t(8261) = 27.47, p < 1 10 -158 ),更多地参与负面角色 ( = 0.162, 95% CI = [0.147, 0.176], t(8261) = 21.87, p < 1 10 -10 ),并展现出更多的正面角色 ( = 0.278, 95% CI = [0.263, 0.293], t(8261) = 35.38, p < 1 10 -254 )。QwQ-32B 相对于 Qwen-2.5-32B-IT 表现出类似的模式,请求增加 ( = 0.200, 95% CI = [0.186, 0.215], t(8261) = 27.21, p < 1 10 -155 ),负面角色增加 ( = 0.450, 95% CI = [0.436, 0.463], t(8261) = 64.77, p < 1 10 -323 ),正面角色增加 ( = 0.312, 95% CI = [0.296, 0.327], t(8261) = 39.17, p < 1 10 -307 )。相比之下,指令微调的模型主要提供指导、观点和建议,而没有互惠的请求行为或情感参与,产生的是单向独白而非模拟对话。

We quantify reciprocal role balance using the Jaccard index, which captures whether both sides of a role pair—asking versus giving for task-oriented roles, and positive versus negative for emotional roles—co-occur within the same reasoning trace. As shown in Fig. 1c, DeepSeek-R1 exhibits significantly higher Jaccard indices for both ask & give ( = 0.222, 95% CI = [0.208, 0.237], t(8261) = 30.21, p < 110-189) and positive & negative roles ( = 0.189, 95% CI = [0.176, 0.203], t(8261) = 27.47, p < 110-158) compared to DeepSeek-V3, indicating that the model coordinates roles reciprocally rather than deploying them in isolation. QwQ-32B shows a similar pattern relative to Qwen-2.5-32B-IT (ask & give: = 0.284 [0.269, 0.299], t(8261) = 37.36, p < 110-281; positive & negative: = 0.200 [0.186, 0.215], t(8261) = 27.24, p < 110-155) (see Supplementary Table 1).

我们使用 Jaccard 指数量化互惠角色平衡,该指数能够捕捉任务导向角色中请求与提供、情感角色中积极与消极是否在同一个推理轨迹中共同出现。如图 1c 所示,DeepSeek-R1 在请求与提供( = 0.222,95% CI = [0.208, 0.237],t(8261) = 30.21,p < 1 10 -189 )和积极与消极角色( = 0.189,95% CI = [0.176, 0.203],t(8261) = 27.47,p < 1 10 -158 )上的 Jaccard 指数均显著高于 DeepSeek-V3,表明该模型是互惠地协调角色,而非孤立地部署角色。QwQ-32B 相对于 Qwen-2.5-32B-IT 表现出类似模式(请求与提供: = 0.284 [0.269, 0.299],t(8261) = 37.36,p < 1 10 -281 ;积极与消极: = 0.200 [0.186, 0.215],t(8261) = 27.24,p < 1 10 -155 )(参见补充表 1)。

We further examine whether conversational behaviours and socio-emotional roles become more pronounced when DeepSeek-R1 faces more difficult tasks. Problem complexity is assessed both by an external LLM-as-judge (Fig. 1d: Gemini-2.5-Pro) or by error rates across conventional instruction-tuned models (Fig. 1e: DeepSeek-V3, Qwen-2.5-32B, Llama-3.3-70B-IT, Llama-3.1-8B-IT). As illustrated in Fig. 1d and 1e, these behaviours appear more frequently when DeepSeek-R1 tackles more complex problems, except for giving orientations and opinions. Consistent patterns across both measures suggest that conversational reasoning is preferentially activated in response to greater problem difficulty. For instance, tasks with the highest complexity scores—such as GPQA (graduate-level science) and challenging math problems—exhibit strong conversational patterns, whereas simple procedural tasks like boolean expressions and basic logical deduction show minimal dialogic behaviour (see Supplementary Table 2).

我们进一步考察当 DeepSeek-R1 面对更困难的任务时,对话行为和社会情感角色是否会更加明显。问题的复杂性通过外部 LLM 作为评判者(图 1d:Gemini-2.5-Pro)或通过传统指令调优模型的错误率(图 1e:DeepSeek-V3、Qwen-2.5-32B、Llama-3.3-70B-IT、Llama-3.1-8B-IT)进行评估。如图 1d 和 1e 所示,当 DeepSeek-R1 处理更复杂的问题时,这些行为出现的频率更高,除了给出方向和观点的情况。两种衡量标准的一致模式表明,对话推理在问题难度增加时更倾向于被激活。例如,具有最高复杂度评分的任务——如 GPQA(研究生级科学)和具有挑战性的数学问题——表现出强烈的对话模式,而像布尔表达式和基本逻辑推理这样的简单程序性任务则显示出极少的对话行为(参见补充表格 2)。

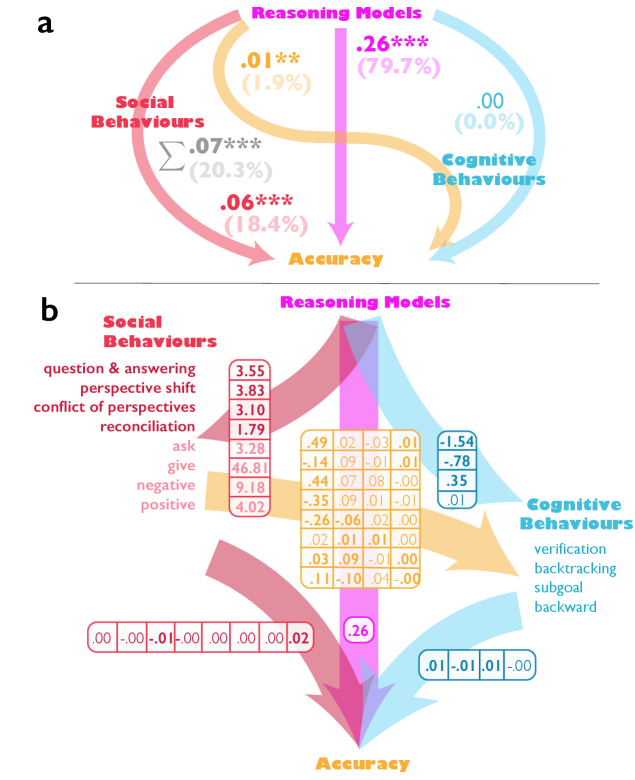

To decompose the accuracy advantage of reasoning models (DeepSeek-R1 and QwQ-32B) using the behavioural mechanisms above, we estimate a structural equation model with four conversational behaviours, four socio-emotional roles, and four cognitive behaviour mediators, using task accuracy as the outcome. Results suggest that conversational behaviours and socio-emotional roles mediate reasoning models’ accuracy advantage, both directly and indirectly through facilitating useful cognitive strategies, such as verification, backtracking, subgoal setting, and backward tracking (See Extended Data Fig. 4; Supplementary Methods: behavioural Pathways Linking Reasoning Models to Accuracy Advantages).

利用上述行为机制分解推理模型(DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B)的准确率优势,我们采用任务准确率作为结果,构建了一个包含四种对话行为、四种社会情感角色和四种认知行为中介的结构方程模型。结果表明,对话行为和社会情感角色通过促进验证、回溯、子目标设定和反向追踪等有用认知策略,直接和间接地介导了推理模型的准确率优势(参见扩展数据图 4;补充方法:连接推理模型与准确率优势的行为路径)。

Conversational Feature Steering Improves Reasoning Accuracy

对话特征引导提升推理准确率

Having observed that conversational behaviours are prevalent in reasoning traces using LLM-as-judge, we next question whether steering behaviours associated with conversations contribute to reasoning performance. We employ mechanistic interpretability methods to identify and manipulate features in the model’s activation space related to conversational behaviours, and examine how steering these features affects the model’s reasoning capabilities. We use sparse autoencoders (SAEs), which decompose neural network activations into a large set of linear, interpretable features56, 57, 58. Specifically, we use an SAE trained on Layer 15’s residual stream activations of DeepSeek-R1-Llama-8B (15-llamascope-slimpj-res-32k), a distilled model derived from DeepSeek-R1 frequently used to conduct interpretability research on LLM reasoning38, 39, 40, 41. SAEs trained on middle layers, including Layer 15, are known to capture key behavioural and semantic features in models6, 58. The SAE was trained on the SlimPajama dataset, a general-purpose, large-scale corpus used to train LLMs from scratch, containing both conversational and non-conversational texts (see Supplementary Table 3 for full SAE hyperparameters)59.

观察到使用 LLM 作为裁判的推理轨迹中普遍存在对话行为后,我们进一步探究与对话相关的引导行为是否会影响推理性能。我们采用机制可解释性方法来识别和操控模型激活空间中与对话行为相关的特征,并检验引导这些特征如何影响模型的推理能力。我们使用稀疏自动编码器(SAEs),将神经网络激活分解为大量线性、可解释的特征 56, 57, 58 。具体而言,我们使用一个在 DeepSeek-R1-Llama-8B(15-llamascope-slimpj-res-32k)第 15 层残差流激活上训练的 SAE,DeepSeek-R1-Llama-8B 是一个从 DeepSeek-R1 衍生出的蒸馏模型,常用于对 LLM 推理进行可解释性研究 38, 39, 40, 41 。已知在中间层(包括第 15 层)上训练的 SAEs 能够捕捉模型中的关键行为和语义特征 6, 58 。 SAE 是在 SlimPajama 数据集上训练的,这是一个通用的、大规模语料库,用于从头开始训练 LLMs,包含对话和非对话文本(有关完整的 SAE 超参数,请参见补充表格 3) 59 。

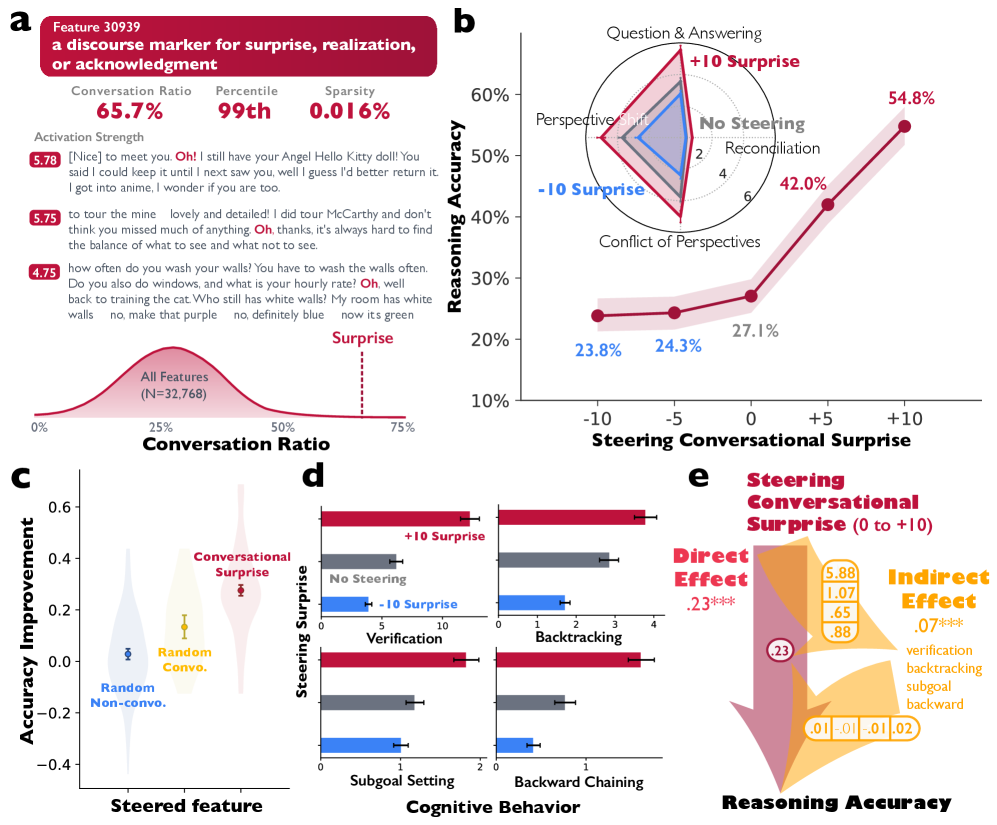

To identify SAE features associated with conversational contexts, we follow a conventional interpretability pipeline60, 61, 56. We first run the SAE on a large-scale corpus (SlimPajama-3B), sampling around 50 contexts where each of the 32,768 features activates to “explain” the role of each feature. These sampled contexts are then used to characterize the feature as in prior literature60, 61, 56. Using LLM-as-judge classification of these contexts (Gemini-2.5-flash-lite), we compute the conversation ratio for each feature—the proportion of feature activations that occur in interpersonal, conversational settings (see Fig. 2a for the distribution across all features). For example, if the conversation ratio is 50%, then in 50% of the instances when the feature is activated, it is used for conversation. We focus on features with conversation ratios above 50% that tend to activate near sentence onsets (i.e., within the first four tokens). From the candidates, we curate feature 30939, summarized as “a discourse marker for surprise, realization, or acknowledgment” by Gemini-2.5-Pro, which activates on tokens like “Oh!” in contexts involving turn-taking and social exchange (see Fig. 2a). This feature exhibits a conversation ratio of 65.7%—placing it in the 99th percentile among all features—while maintaining high sparsity (0.016% of tokens), indicating that it captures a specific conversational phenomenon rather than general linguistic patterns. We select this feature because prior literature suggests that expressions of surprise signal a shift in contrasting perspectives characteristic of social coordination and affiliation62, 63.

为了识别与对话情境相关的 SAE 特征,我们遵循传统的可解释性流程 60, 61, 56 。我们首先在大型语料库(SlimPajama-3B)上运行 SAE,采样约 50 个情境,其中每个 32,768 个特征被激活以“解释”每个特征的作用。然后使用这些采样的情境来表征特征,如先前的文献 60, 61, 56 所述。我们使用 LLM 作为裁判对这些情境进行分类(Gemini-2.5-flash-lite),计算每个特征的对话比率——即特征激活发生在人际、对话情境中的比例(所有特征的分布情况见图 2a)。例如,如果对话比率为 50%,那么在特征被激活的 50%的实例中,它用于对话。我们关注对话比率超过 50%且倾向于在句子开头附近激活(即在前四个 token 内)的特征。从候选特征中,我们筛选出特征 30939,Gemini-2.5-Pro 将其总结为“用于惊讶、意识到或确认的语篇标记”,该特征在涉及轮流发言和社会交换的情境中(如“哦!”这样的 token 上)被激活(见图 2a)。 这一特征展现出 65.7%的对话比例,在所有特征中排名前 1%,同时保持高稀疏度(0.016%的 token),表明它捕捉的是特定的对话现象而非普遍的语言模式。我们选择这一特征是因为已有文献表明,惊讶的表达标志着社会协调和归属感所特有的对比视角的转变 62, 63 。

图 2:引导对话特征可提升推理能力。a,DeepSeek-R1-Llama-8B 中稀疏自编码器特征 30939 的示意图,总结为对话场景中用于表达惊讶、顿悟或确认的语篇标记。对话比例表示该特征被激活的所有场景中对话场景的比例。百分位数表示该特征对话比例在所有特征中的排名( )。稀疏性指该特征在整个语料库中激活的 token 比例。激活强度显示在激活度最高的示例中的激活幅度。示例展示了该特征在对话轮流语境中的激活情况。b,使用激活添加方法进行的引导实验结果。将特征 30939 向量以 10 的强度添加,使复杂计数任务的准确率翻倍。插图显示了引导该特征引起的对话行为的因果变化。 c, 小提琴图展示了从转向特征 30939 中获得的准确率提升,与随机选择的一个对话式 SAE 特征和随机选择的一个非对话式 SAE 特征进行比较。d, 认知行为——包括验证、回溯、子目标设定和反向链接——与转向特征 30939 的激活因果关系相关。e, 结构方程模型结果展示了从 0 转向到 特征 30939,对推理准确率有直接效应,并通过认知行为(验证、子目标设定和反向链接)存在显著的间接效应。粗体系数表示统计显著性( )。*** , ** ,* 。

We examine whether steering this feature causally induces conversational behaviours and improves reasoning accuracy using the activation addition method, which adds scaled feature vectors to model activations during generation. Specifically, we use the Countdown game, a benchmark commonly used to evaluate LLM multi-step reasoning capabilities8, 52. In the Countdown task, the model must combine a given set of numbers using basic arithmetic operations (+, , , ) and parentheses to reach a target value—for example, given inputs 25, 30, 3, 4 and target 32, a valid solution is (30 25 + 3) 4 = 328, 52. We use the sample of 1,024 Countdown problems. We prompt the model to generate chain-of-thought reasoning, and at each token generation step, we add the feature 30939 vector (scaled by the steering strength) to layer 15 activations.

我们使用激活加成方法来检验是否通过因果引导这一特征能够诱导对话行为并提高推理准确性,该方法在生成过程中将缩放的特征向量添加到模型激活中。具体来说,我们使用倒计时游戏,这是一个常用的基准测试,用于评估 LLM 的多步推理能力 8, 52 。在倒计时任务中,模型必须使用基本的算术运算(+、 、 、 )和括号来组合给定的数字集合,以达到目标值——例如,给定输入 25、30、3、4 和目标值 32,一个有效的解决方案是(30 25 + 3) 4 = 32 8, 52 。我们使用了 1,024 个倒计时问题的样本。我们提示模型生成思维链推理,并在每个标记生成步骤中,将特征向量 30939(按引导强度缩放)添加到第 15 层的激活中。

As shown in Fig. 2b, steering the conversational surprise feature with positive direction (+10) doubles accuracy from 27.1% to 54.8% in the Countdown task, while steering in the negative direction (10) reduces accuracy to 23.8%. The radar plot inset reveals that positive steering (from 0 to +10) simultaneously increases all four conversational behaviours—more question-answering ( = 2.199, 95% CI = [1.648, 2.750], t(1023) = 7.83, p < 110-14), perspective shifts ( = 1.160, 95% CI = [0.665, 1.655], t(1023) = 4.60, p < 110-5), conflict of perspectives ( = 1.062, 95% CI = [0.376, 1.749], t(1023) = 3.04, p = 0.002), and reconciliation ( = 0.423, 95% CI = [0.349, 0.497], t(1023) = 11.21, p < 110-27), controlling for problem fixed-effects and log-transformed reasoning trace length. Negative steering from 0 to -10 suppresses them, reducing question-answering ( = 0.831, 95% CI = [1.154, 0.508], t(1023) = 5.05, p < 110-6), perspective shifts ( = 0.966, 95% CI = [1.262, 0.670], t(1023) = 6.41, p < 110-9), conflict of perspectives ( = 1.347, 95% CI = [1.748, 0.946], t(1023) = 6.60, p < 110-10), and reconciliation ( = 0.052, 95% CI = [0.103, 0.001], t(1023) = 1.99, p = 0.046). For instance, as shown in Extended Data Table 1, positive steering (+10) induces reasoning traces where the model actively challenges prior approaches (“Wait, let me see… Another idea…”), showing perspective shift and conflicts of perspectives, whereas negative steering (10) produces relatively flat, declarative reasoning without internal debate.

如图 2b 所示,将对话意外特征正向引导(+10)使计数器任务中的准确率从 27.1%提升至 54.8%,而负向引导( 10)则将准确率降至 23.8%。雷达图插图显示,正向引导(从 0 到+10)同时提升了所有四种对话行为——更多问答( = 2.199, 95% CI = [1.648, 2.750], t(1023) = 7.83, p < 1 10 -14 )、视角转换( = 1.160, 95% CI = [0.665, 1.655], t(1023) = 4.60, p < 1 10 -5 )、视角冲突( = 1.062, 95% CI = [0.376, 1.749], t(1023) = 3.04, p = 0.002)和和解( = 0.423, 95% CI = [0.349, 0.497], t(1023) = 11.21, p < 1 10 -27 ),同时控制问题固定效应和对数转换的推理轨迹长度。从 0 到-10 的负向引导则抑制了这些行为,降低了问答( = 0.831, 95% CI = [ 1.154, 0.508], t(1023) = 5.05, p < 1 10 -6 )、视角转换( = 0.966, 95% CI = [ 1.262, 0.670], t(1023) = 6.41, p < 1 10 -9 )、视角冲突( = 1.347, 95% CI = [ 1.748, 0.946], t(1023) = 6.60, p < 1 10 -10 ), 和和解 ( = 0.052, 95% CI = [ 0.103, 0.001], t(1023) = 1.99, p = 0.046)。例如,正如扩展数据表 1 所示,正向引导(+10)会引发推理痕迹,其中模型会主动挑战先前方法(“等等,让我看看……还有另一个想法……”),显示出视角转换和视角冲突,而负向引导( 10)则产生相对平稳、陈述性的推理,没有内部辩论。

To examine whether this effect is specific to conversational features rather than a general property of SAE steering, we compare accuracy improvements across three conditions: (1) steering the conversational surprise feature (Feature 30939), steering a randomly selected conversational feature, and steering a randomly selected non-conversational feature (Fig. 2c). A random conversational feature is defined as any feature whose conversation ratio is above the average and tends to activate near sentence onset (i.e., first four tokens), which are more closely associated with conversational styles than other features. All steering strengths are defined as the maximum activation strength across sampled instances of feature activations (SlimPajama-3B), multiplied by 2. The conversational surprise feature produces substantially larger accuracy gains than both random conversational features and non-conversational features (see Fig. 2c). Steering any random conversational feature also significantly improves reasoning by 4.17% more than any random non-reasoning feature ( = 0.042, 95% CI = [0.016, 0.068], t(1023)=3.14, p=0.002). This specificity suggests that conversational dynamics, rather than arbitrary perturbations to model activations, drive the observed improvements.

为了检验这种效应是否特定于对话特征,而非 SAE 转向的一般属性,我们比较了三种条件下的准确率提升:(1) 转向对话意外特征(特征 30939)、转向随机选择的一个对话特征,以及转向随机选择的一个非对话特征(图 2c)。随机对话特征被定义为任何对话比例高于平均值且倾向于在句子起始附近(即前四个 token)激活的特征,这些特征与其他特征相比,更紧密地与对话风格相关。所有转向强度定义为特征激活的样本实例中的最大激活强度(SlimPajama-3B)乘以 2。对话意外特征产生的准确率提升远大于随机对话特征和非对话特征(见图 2c)。转向任何随机对话特征也比转向任何随机非推理特征显著提高了 4.17%的推理能力( = 0.042,95% CI = [0.016, 0.068],t(1023)=3.14,p=0.002)。 这种特殊性表明,是会话动态而非对模型激活的任意扰动,推动了观察到的改进。

We further investigate the mechanism by which conversational steering enhances reasoning. Prior work has identified cognitive behaviours—verification, backtracking, subgoal setting, and backward chaining —as key contributors to reasoning accuracy in language models8. As shown in Fig. 2d, steering feature 30939 toward positive values (0 to +10) systematically increases all four cognitive behaviours: verification (Difference = 5.815, 95% CI=[4.922, 6.709], t(1023)=12.77, p < 110-34), backtracking (Difference = 0.881, 95% CI=[0.515, 1.248], t(1023)=4.72, p < 110-5), subgoal setting (Difference = 0.621, 95% CI=[0.440, 0.803], t(1023)=6.72, p < 110-10), and backward chaining (Difference = 0.809, 95% CI=[0.633, 0.985], t(1023)=9.02, p < 110-18) rise monotonically with steering strength. Steering toward negative values (0 to -10) suppresses these behaviours (verification: Difference = -2.302, 95% CI=[-2.892, -1.711], t(1023)=7.65, p < 110-13; backtracking: Difference = -1.138, 95% CI=[-1.410, -0.867], t(1023)=8.24, p < 110-15; subgoal setting: Difference = -0.171, 95% CI=[-0.305, -0.036], t(1023)=2.48, p = 0.013; backward chaining: Difference = -0.353, 95% CI=[-0.487, -0.219], t(1023)=5.18, p < 110-6) based on paired t-tests. This suggests that conversational features may improve reasoning, in part, by facilitating the deployment of effective cognitive strategies.

我们进一步研究了对话引导增强推理的机制。先前研究已经确定了认知行为——验证、回溯、子目标设置和反向链接——作为语言模型推理准确性的关键贡献因素 8 。如图 2d 所示,将引导特征 30939 推向正值(0 至+10)系统地增加了所有四种认知行为:验证(差异=5.815,95%置信区间=[4.922, 6.709],t(1023)=12.77,p < 1 10 -34 ),回溯(差异=0.881,95%置信区间=[0.515, 1.248],t(1023)=4.72,p < 1 10 -5 ),子目标设置(差异=0.621,95%置信区间=[0.440, 0.803],t(1023)=6.72,p < 1 10 -10 ),以及反向链接(差异=0.809,95%置信区间=[0.633, 0.985],t(1023)=9.02,p < 1 10 -18 ),这些行为随着引导强度的增加而单调上升。将引导推向负值(0 至-10)则抑制了这些行为(验证:差异=-2.302,95%置信区间=[-2.892, -1.711],t(1023)=7.65,p < 1 10 -13 ;回溯:差异=-1.138,95%置信区间=[-1.410, -0.867],t(1023)=8.24,p < 1 10 -15 ;子目标设置:差异=-0.171,95%置信区间=[-0.305, -0.036],t(1023)=2.48,p = 0.)013; 反向链:差异 = -0.353,95%置信区间=[-0.487, -0.219],t(1023)=5.18,p < 1 10 -6 ) 基于配对 t 检验。这表明对话特征可能通过促进有效认知策略的运用,部分提升了推理能力。

To disentangle direct and indirect effects, we fit a structural equation model to examine the pathways from steering conversational surprise (feature 30939) to accuracy (Fig. 2e). The model indicates that increasing steering feature 30939 from 0 to +10 yields both a significant direct effect on reasoning accuracy ( = .228, 95% CI = [.183, .273], z=9.98, p < 110-22, N=2048) and a significant indirect effect mediated by cognitive behaviours ( = .066, 95% CI = [.046, .086], z=6.38, p < 110-10, N=2048). Collectively, these findings suggest that conversational features enhance reasoning by directly enabling more effective exploration of the solution space, but also by scaffolding the cognitive strategies that support systematic problem solving.

为区分直接和间接效应,我们拟合了一个结构方程模型来检验从引导对话意外(特征 30939)到准确性的路径(图 2e)。模型显示,将引导特征 30939 从 0 增加到+10,既对推理准确性产生显著直接效应( = .228,95%置信区间 = [.183, .273],z=9.98,p < 1 10 -22 ,N=2048),也通过认知行为产生显著间接效应( = .066,95%置信区间 = [.046, .086],z=6.38,p < 1 10 -10 ,N=2048)。综合来看,这些发现表明对话特征通过直接促进对解空间的更有效探索,以及通过构建支持系统化问题解决的认知策略,增强了推理能力。

Diversity of Implicit Perspectives

隐性视角的多样性

Beyond task accuracy, we examine whether DeepSeek-R1 increases the diversity of perspectives expressed within a reasoning trace. In human societies, conversations and socio-emotional role-taking expand the range of viewpoints and domain knowledge brought into problem solving. Differences of perspective give rise to conflict, debate, and resolution. We evaluate whether similar perspective diversity emerges in DeepSeek-R1 by analyzing personality and expertise variation among the distinct reasoning “perspectives” participating in each reasoning trace.

除了任务准确性之外,我们还考察 DeepSeek-R1 是否增加了推理轨迹中表达的视角多样性。在人类社会中,对话和社会情感角色扮演扩展了问题解决中引入的观点范围和领域知识。视角的差异会导致冲突、辩论和解决。我们通过分析每个推理轨迹中参与的不同推理“视角”之间的性格和专业知识差异,评估 DeepSeek-R1 是否出现了类似的视角多样性。

We first use an external LLM-as-judge (Gemini-2.5-Pro), prompting it to identify the diversity of implicit conversational perspectives within reasoning traces of DeepSeek-R1, QwQ-32B, and other instruction-tuned models. Specifically, the model infers the number of perspectives underlying each reasoning trace, the personality traits and domain expertise associated with each perspective, and a segmentation of the full reasoning trace by perspective (see Methods: Implicit Perspectives). Given a complete reasoning trace, the LLM-as-judge first infers the number of distinct perspectives present, which is shown in Fig. 1d. It then characterizes each perspective’s personality traits using the BFI-10 (10-Item Big Five Personality Scale) questionnaire64, along with a short free-form description of the perspective’s domain expertise. Finally, the LLM-as-judge attributes each token in the reasoning trace to a specific perspective (i.e., who said this word). Personality diversity is estimated using the standard deviation of inferred personality traits for each Big-5 dimension, while domain expertise diversity is estimated using the mean cosine distance between embedding of each domain expertise description and the average embedding. See Methods: Implicit Perspectives and Supplementary Method: LLM-as-judge prompts (“Persona identification” and “Persona segmentation”) for details.

我们首先使用一个外部 LLM 作为裁判(Gemini-2.5-Pro),提示它识别 DeepSeek-R1、QwQ-32B 和其他指令微调模型推理轨迹中隐含对话视角的多样性。具体来说,该模型推断每个推理轨迹背后所隐含的视角数量、每个视角相关联的性格特征和领域专业知识,以及按视角对完整推理轨迹进行分割(参见方法:隐含视角)。对于一个完整的推理轨迹,LLM 作为裁判首先推断其中存在的不同视角数量,如图 1d 所示。然后,它使用 BFI-10(10 项五大性格量表)问卷 64 来描述每个视角的性格特征,并附上对该视角领域专业知识的简短自由描述。最后,LLM 作为裁判将推理轨迹中的每个词元分配给一个特定的视角(即:谁说了这句话)。 人格多样性通过每个 Big-5 维度的推断人格特质的方差来估计,而领域专业知识多样性则通过每个领域专业知识描述的嵌入与平均嵌入之间的平均余弦距离来估计。详情请参见方法:隐式视角和补充方法:LLM 作为评判者提示(“人格识别”和“人格分割”)。

For instance, in a chemistry reasoning trace requiring multi-step synthesis analysis, the LLM-as-judge identifies five perspectives, including a critical verifier (low agreeableness, high conscientiousness) who skeptically re-evaluates assumptions, and an expert in making associations (high openness) who recalls analogous reactions. In a creative writing trace where the model rewrites the sentence “I flung my hatred into the burning fire,” seven perspectives emerge, including a creative ideator (highest Openness and Extraversion) who generates stylistic alternatives and a semantic fidelity checker (low agreeableness, high neuroticism) who prevents scope creep—“But that adds ‘deep-seated’ which wasn’t in the original”. DeepSeek-V3’s trace reflects only a single generalist perspective combining all functions without differentiation (see Supplementary Methods: Annotation Examples).

例如,在一个需要多步合成分析的化学推理追踪中,作为评判者的 LLM 识别出五个视角,包括一个批判性验证者(低宜人性、高责任心)对假设进行怀疑重估,以及一个擅长建立关联的专家(高开放性)回忆起类似反应。在一个创造性写作追踪中,当模型重写句子“我将我的仇恨抛入燃烧的火焰”时,会出现七个视角,包括一个创意构思者(开放性和外向性最高)生成风格化替代方案,以及一个语义保真度检查者(低宜人性、高神经质)防止范围蔓延——“但这增加了‘根深蒂固’,而原文中并没有”。DeepSeek-V3 的追踪仅反映了一个结合所有功能而无差异的单一通用视角(参见补充方法:标注示例)。

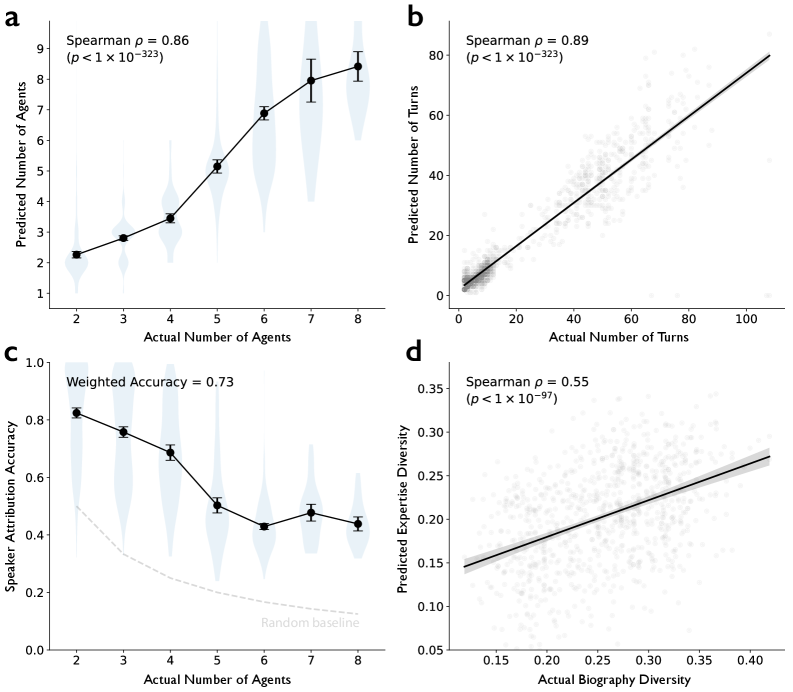

Using the Intelligence Squared Debates Corpus—a dataset of human argumentative conversations (N=1,196 conversations) among two to eight participants—we first validate the accuracy of the LLM-as-judge in identifying distinct voices within a conversation. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 5, we find that the LLM-as-judge can accurately predict the number of distinct individuals underlying each conversation, even when speaker labels are hidden and the dialogue is concatenated into a single block of text (Spearman’s = 0.86, 95% CI = [0.84, 0.87], z = 44.7, p < 1×10-323). We also find that the LLM-as-judge can accurately predict the number of distinct turns (Spearman’s = 0.89, 95% CI = [0.88, 0.90], z = 49.2, p < 1×10-323) and correctly attribute each token to a speaker. When there are two speakers, the accuracy is 82%; for three speakers, 76%; and for four speakers, 69%. Accuracy weighted by the predicted number of implicit perspectives underlying LLM reasoning trace is 73%. Because the Intelligence Squared Debates Corpus includes biographical information about debate participants, we further verify that expertise diversity inferred by LLM-as-judge and embeddings predicts the actual diversity among participants’ ground-truth biographies (Spearman’s = 0.55, 95% CI = [0.51, 0.59], z = 21.4, p < 1×10-97). Together, these results suggest that LLM-as-judge can capture meaningful diversity patterns in conversational agents that correspond to observed diversity in real human conversations (see Methods: Implicit Perspectives - Validation for details).

使用 Intelligence Squared 辩论语料库——一个包含人类辩论对话的数据集(N=1,196 次对话),其中参与人数为两到八人——我们首先验证了作为裁判的 LLM 在识别对话中不同声音方面的准确性。如图 5 所示,我们发现作为裁判的 LLM 能够准确预测每个对话背后不同个体的数量,即使说话人标签被隐藏且对话被连接成一个文本块(Spearman’s = 0.86, 95% CI = [0.84, 0.87], z = 44.7, p < 1×10 -323 )。我们还发现作为裁判的 LLM 能够准确预测不同轮次的数量(Spearman’s = 0.89, 95% CI = [0.88, 0.90], z = 49.2, p < 1×10 -323 ),并能正确地将每个词元分配给说话人。 当存在两位说话者时,准确率为 82%;三位说话者时,76%;四位说话者时,69%。基于 LLM 推理轨迹中预测的潜在隐含视角数量进行加权计算的准确率为 73%。由于 Intelligence Squared 辩论语料库包含了辩论参与者的传记信息,我们进一步验证了 LLM 作为评判者推断的专业知识多样性和嵌入向量预测了参与者实际传记中的真实多样性(Spearman’s = 0.55, 95% CI = [0.51, 0.59], z = 21.4, p < 1×10 -97 )。综合这些结果表明,LLM 作为评判者能够捕捉到对话代理中的有意义多样性模式,这些模式与真实人类对话中观察到的多样性相对应(参见方法:隐含视角 - 验证部分以获取详细信息)。

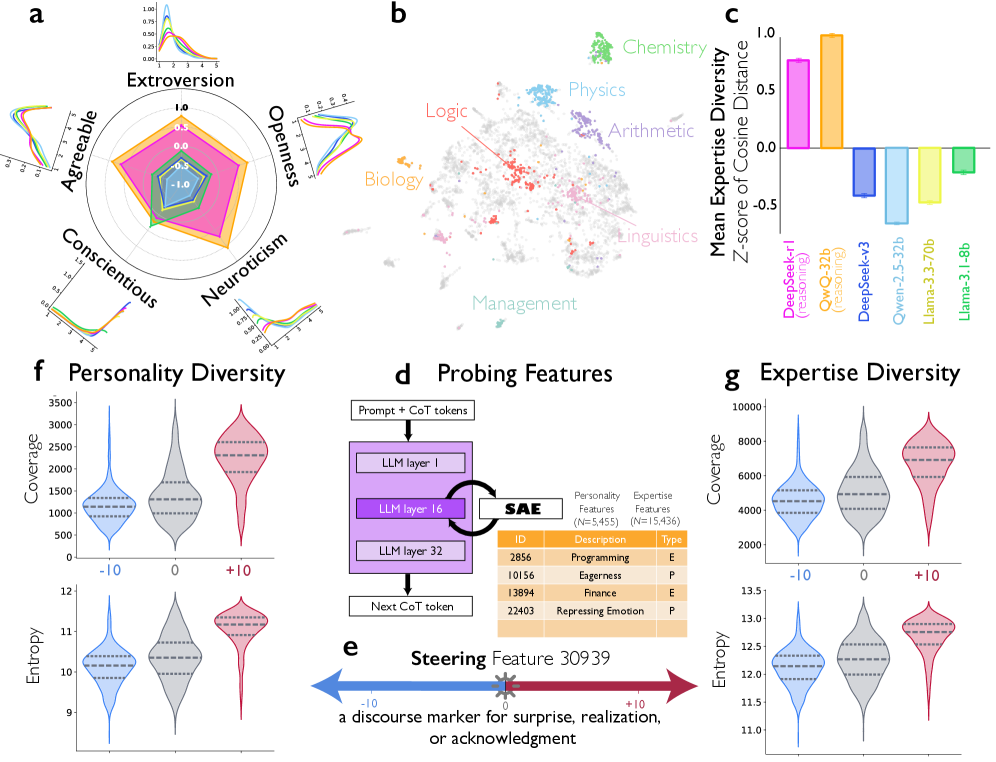

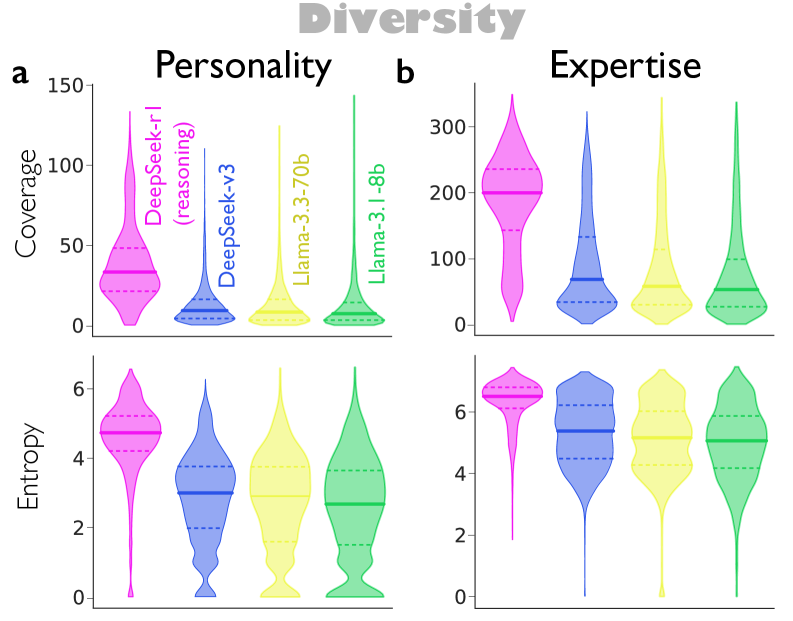

As shown in Fig. 3a, we find that DeepSeek-R1 and QwQ-32B produce significantly higher personality diversity, controlling for the number of perspectives. DeepSeek-R1 shows particularly higher diversity along extraversion ( = 0.103, 95% CI = [0.075, 0.131], t = 7.16, p < 1×10-13), agreeableness ( = 0.297, 95% CI = [0.271, 0.323], t = 22.65, p < 1×10-113), neuroticism ( = 0.567, 95% CI = [0.542, 0.592], t = 44.57, p < 1×10-323), and openness ( = 0.110, 95% CI = [0.083, 0.137], t = 8.06, p < 1×10-16), compared to DeepSeek-V3. Similarly, QwQ-32B shows higher diversity in extraversion ( = 0.253, 95% CI = [0.223, 0.282], t = 16.78, p < 1×10-63), agreeableness ( = 0.490, 95% CI = [0.462, 0.519], t = 34.09, p < 1×10-254), neuroticism ( = 0.825, 95% CI = [0.797, 0.852], t = 58.49, p < 1×10-323), and openness ( = 0.268, 95% CI = [0.238, 0.298], t = 17.41, p < 1×10-68), than Qwen-2.5-32B-IT. In contrast, conscientiousness diversity is lower in DeepSeek-R1 ( = 0.291, 95% CI = [0.317, 0.265], t = 21.90, p < 1×10-106) and QwQ-32B ( = 0.402, 95% CI = [0.435, 0.369], t = 23.79, p < 1×10-125), suggesting that the reasoning model voices appear more consistently engaged and dutiful. The particularly large effects for agreeableness and neuroticism—traits associated with interpersonal harmony and emotional reactivity—suggest that reasoning models generate perspectives that more frequently disagree with and challenge one another. Interestingly, this pattern aligns with prior literature on human team diversity, which suggests that variability in extraversion and neuroticism enhances team performance, whereas variability in conscientiousness impairs it21, 65.

如图 3a 所示,我们发现 DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B 在控制视角数量的情况下,产生了显著更高的人格多样性。与 DeepSeek-V3 相比,DeepSeek-R1 在外向性( = 0.103, 95% CI = [0.075, 0.131], t = 7.16, p < 1×10 -13 )、宜人性( = 0.297, 95% CI = [0.271, 0.323], t = 22.65, p < 1×10 -113 )、神经质( = 0.567, 95% CI = [0.542, 0.592], t = 44.57, p < 1×10 -323 )和开放性( = 0.110, 95% CI = [0.083, 0.137], t = 8.06, p < 1×10 -16 )方面表现出更高的多样性。同样,与 Qwen-2.5-32B-IT 相比,QwQ-32B 在外向性( = 0.253, 95% CI = [0.223, 0.282], t = 16.78, p < 1×10 -63 )、宜人性( = 0.490, 95% CI = [0.462, 0.519], t = 34.09, p < 1×10 -254 )、神经质( = 0.825, 95% CI = [0.797, 0.852], t = 58.49, p < 1×10 -323 )和开放性( = 0.268, 95% CI = [0.238, 0.298], t = 17.41, p < 1×10 -68 )方面也表现出更高的多样性。相比之下,DeepSeek-R1( = 0.291, 95% CI = [ 0.317, 0.265], t = 21.90, p < 1×10 -106 )和 QwQ-32B( = 0.402, 95% CI = [ 0.435, 0.369], t = 23.)的尽责性多样性较低。79, p < 1×10 -125 ), 表明推理模型的参与度和责任感表现更为一致。对于宜人性与神经质这两个与人际和谐及情绪反应相关的特质而言,其尤为显著的影响表明推理模型生成的观点更频繁地相互分歧和挑战。有趣的是,这一模式与先前关于人类团队多样性的文献相吻合,该文献指出外向性和神经质性的差异性能够提升团队表现,而责任心方面的差异性则会损害团队表现 21, 65 。

图 3:推理轨迹中的性格与专业多样性。a,使用 LLM 作为评判者和 BFI-10(五因素人格量表 10 项版本)从每个推理轨迹中推断出的隐式推理视角的性格多样性。对于每个五因素维度,多样性通过推断性格的标准差来量化。推理模型(DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B)在开放性、神经质、宜人性和外向性上表现出显著更高的多样性。核密度估计(KDE)图显示了性格特征在推理轨迹中的分布。b,由 LLM 作为评判者识别的专业嵌入空间,使用 UMAP 投影到二维空间,并以能量最小化布局渲染,揭示了连贯且一致的专业邻近性。c,从每个推理轨迹中推断出的隐式推理视角的专业多样性,通过每个与语义空间中所有嵌入质心的余弦距离的均值来衡量。推理模型比非推理模型的专业多样性大得多。 d, 引导实验中稀疏自编码器(SAE)的架构和特征识别。e, 引导实验的设计。SAE 特征 30939——捕捉表示惊讶、实现或确认的语篇标记,暗示角色和视角的转换——在引导强度为 10 时增加或减少。示例推理轨迹表明,负向引导导致线性思维链轨迹,无引导产生微妙的视角转换以实现自我检查,正向引导导致频繁且显著的视角转换,探索根本不同的解决方案策略。f, g, 在特征 30939 引导下,SAE 与人格相关(f)和专业知识相关(g)特征的覆盖率和熵分布。误差线表示 95%置信区间;实线水平线表示中位数,虚线表示四分位距(25th–75th 百分位数)。

We next examine expertise diversity, defined as the dispersion of conversing agents within the embedding space of inferred domain expertise descriptions. For example, when perspectives drawing on what the models judge as expertise in theoretical physics, analytic reasoning, finance, and creative writing co-occur in the same reasoning trace, the mean distance between their expertise embeddings manifests as large (Fig. 3b). As shown in Fig. 3c, DeepSeek-R1 exhibits significantly higher expertise diversity ( = 0.179, 95% CI = [0.161, 0.196], t = 20.11, p < 1×10-89) than DeepSeek-V3, and QwQ-32B shows higher expertise diversity ( = 0.250, 95% CI = [0.231, 0.269], t = 25.50, p < 1×10-142) than Qwen-2.5-32B-IT, across its implicit reasoning agents than non-reasoning models.

我们接下来考察专业多样性,定义为在推断的领域专业知识描述的嵌入空间中,对话代理的分散程度。例如,当模型认为的理论物理学、分析推理、金融和创意写作等视角在同一推理轨迹中同时出现时,它们的专业知识嵌入之间的平均距离表现为较大(图 3b)。如图 3c 所示,DeepSeek-R1 的专业多样性显著高于 DeepSeek-V3( = 0.179,95%置信区间为[0.161, 0.196],t = 20.11,p < 1×10 -89 ),而 QwQ-32B 的专业多样性( = 0.250,95%置信区间为[0.231, 0.269],t = 25.50,p < 1×10 -142 )高于 Qwen-2.5-32B-IT,在其隐式推理代理中高于非推理模型。

To examine whether the personality- and expertise-related diversity observed in DeepSeek-R1’s and QwQ-32B’s reasoning traces is reflected in the internal representation space of LLMs, we analyze activations of DeepSeek-R1-Llama-8B’s sparse autoencoder (SAE) features. Prior work has shown that high-level persona traits, such as personalities, cultural perspectives, and topics, are linearly represented in LLM activation space and can be steered66, 67, 6. We steer a conversational feature (i.e., Feature 30939; a discourse marker for surprise, realization, or acknowledgment) with strength of +10 or 10 inside the activation space of DeepSeek-R1-Llama-8B, and probe how personality- and expertise-related features are activated in the steered reasoning traces (see Methods: SAE feature steering).

为了检验 DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ-32B 推理轨迹中观察到的与性格和专业知识相关的多样性是否反映在 LLMs 的内部表示空间中,我们分析了 DeepSeek-R1-Llama-8B 的稀疏自动编码器(SAE)特征的激活情况。先前研究表明,高级性格特征(如性格、文化视角和主题)在 LLM 的激活空间中呈线性表示,并且可以被引导 66, 67, 6 。我们在 DeepSeek-R1-Llama-8B 的激活空间内以+10 或 10 的强度引导一个对话特征(即特征 30939;用于表示惊讶、顿悟或确认的语篇标记),并探究在引导的推理轨迹中,与性格和专业知识相关的特征是如何被激活的(参见方法:SAE 特征引导)。

We first classify each of the 32,768 features as personality-related (e.g., eagerness, expressions of frustration), expertise-related (e.g., programming terminology, financial concepts), or other using an LLM-as-judge approach. We quantify diversity using two complementary measures: coverage, the number of unique personality- or expertise-related features activated across the reasoning trace, and entropy, which captures how evenly activations are distributed across tokens rather than concentrated in a few. Using DeepSeek-R1 reasoning traces, we show that these traces indeed activate more diverse personality-related and expertise-related features, which corroborates our earlier LLM-as-judge results (see Extended Data Fig. 6). For statistical tests, we control for reasoning trace length and problem fixed effects to show that steering conversational surprise activates genuinely more diverse features rather than simply producing longer outputs.

我们首先使用以 LLM 为裁判的方法,将 32,768 个特征分类为与性格相关(例如,热情、沮丧的表达)、与专业领域相关(例如,编程术语、金融概念)或其他类别。我们使用两个互补的指标来量化多样性:覆盖度,即推理过程中激活的独特性格或专业领域相关特征的数目,以及熵,它捕捉了激活在标记(tokens)上分布的均匀性,而不是集中在少数几个标记上。使用 DeepSeek-R1 推理轨迹,我们表明这些轨迹确实激活了更多样化的性格相关和专业领域相关特征,这与我们早期的以 LLM 为裁判的结果相印证(参见扩展数据图 6)。在统计测试中,我们控制了推理轨迹长度和问题固定效应,以表明引导对话的意外性确实激活了更多样化的特征,而不仅仅是产生更长的输出。

As shown in Fig. 3e–f, steering with +10 strength causes reasoning traces to activate a wider coverage of both personality-related features ( = 315.915, 95% CI = [277.320, 354.509], t = 16.04, p < 1×10-323) and expertise-related features ( = 391.312, 95% CI = [313.743, 468.880], t = 9.89, p < 1×10-323) compared to unsteered traces, controlling for reasoning trace length and problem fixed effects. For example, after steering, personality-related features such as “informal expressions of confusion or frustration” (Feature 21065), “phrases related to social interaction and community engagement” (Feature 26139), and “references to emotional or sensational themes in narratives” (Feature 14476) are activated more frequently (see Supplementary Table 4 and 5).

如图 3e–f 所示,使用+10 强度进行引导时,推理轨迹激活了更广泛的人格相关特征( = 315.915,95%置信区间=[277.320, 354.509],t=16.04,p < 1×10 -323 )和专业知识相关特征( = 391.312,95%置信区间=[313.743, 468.880],t=9.89,p < 1×10 -323 ),相比之下,未引导的轨迹在控制推理轨迹长度和问题固定效应的情况下表现不同。例如,引导后,“表达困惑或沮丧的非正式方式”(特征 21065)、“与社会互动和社区参与相关的短语”(特征 26139)以及“叙事中涉及情感或刺激性主题的引用”(特征 14476)等人格相关特征被更频繁地激活(参见补充表 4 和 5)。

To further examine that this increased diversity reflects a broader distribution of activated features rather than simply generating more tokens, we measure the Shannon entropy of feature activations. Higher entropy indicates that activations are more evenly distributed across diverse features, rather than concentrated in a few dominant ones. Steered traces exhibit higher entropy of both personality-related features ( = 0.262, 95% CI = [0.227, 0.298], t = 14.48, p < 1×10-323) and expertise-related features ( = 0.096, 95% CI = [0.075, 0.117], t = 9.02, p < 1×10-323) than unsteered traces, confirming that steering induces more diverse feature activations beyond merely increasing output length.

为了进一步检验这种多样性增加是否反映了激活特征的更广泛分布,而非仅仅是生成更多符号,我们测量了特征激活的香农熵。更高的熵表明激活在多样化的特征中分布更均匀,而非集中在少数主导特征上。引导轨迹在人格相关特征( = 0.262, 95% CI = [0.227, 0.298], t = 14.48, p < 1×10 -323 )和专业知识相关特征( = 0.096, 95% CI = [0.075, 0.117], t = 9.02, p < 1×10 -323 )的熵值均高于非引导轨迹,证实引导不仅增加了输出长度,还诱导了更多样化的特征激活。

Reinforcement Learning Experiments

强化学习实验

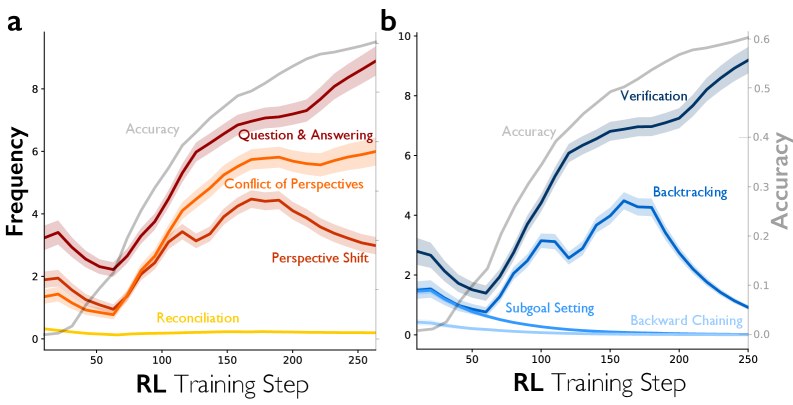

To further examine whether LLMs self-reinforce conversational behaviours when rewarded for correct answers, we implement a self-taught reinforcement learning (RL) experiment. In this setup, the model explores solution strategies for the Countdown arithmetic puzzle game8, 52, where the model must combine a given set of numbers using basic arithmetic operations (+, , ×, ÷) and parentheses to reach a target. We also replicate these findings on political misinformation detection, where models discriminate between true and fabricated political headlines.

为了进一步检验 LLMs 在因正确答案获得奖励时是否会自我强化对话行为,我们实施了一个自教学强化学习(RL)实验。在该设置中,模型探索解决 Countdown 算术谜题游戏的策略,其中模型必须使用基本算术运算(+、 、×、÷)和括号组合给定的数字以达到目标。我们还将在政治虚假信息检测上复制这些发现,其中模型需区分真实与编造的政治标题。

Following the reward architecture of DeepSeek-R14, we reward accuracy and correct format (i.e., wrapping reasoning between <think> and </think> tags and answers between <answer> and </answer> tags) with a simple weighted reward: accuracy × 0.9 + format × 0.1. Crucially, we do not directly reward conversational or cognitive behaviours. We implement Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)68 using the Verl framework69, training for 250 steps (see Supplementary Table 6 for hyperparameters). We use Qwen-2.5-3B, a pre-trained model without any instruction-tuning, prompted to solve the Countdown task with a chain of thought (see Methods: Reinforcement learning experiments).

遵循 DeepSeek-R1 4 的奖励架构,我们用简单的加权奖励来奖励准确性和正确格式(即推理部分用 和 标签包裹,答案部分用 和 标签包裹):准确性 × 0.9 + 格式 × 0.1。关键在于,我们不直接奖励对话或认知行为。我们使用 Verl 框架 69 实现近端策略优化(PPO) 68 ,训练 250 步(超参数见补充表 6)。我们使用未经指令微调的预训练模型 Qwen-2.5-3B,提示其用思维链解决 Countdown 任务(参见方法:强化学习实验)。

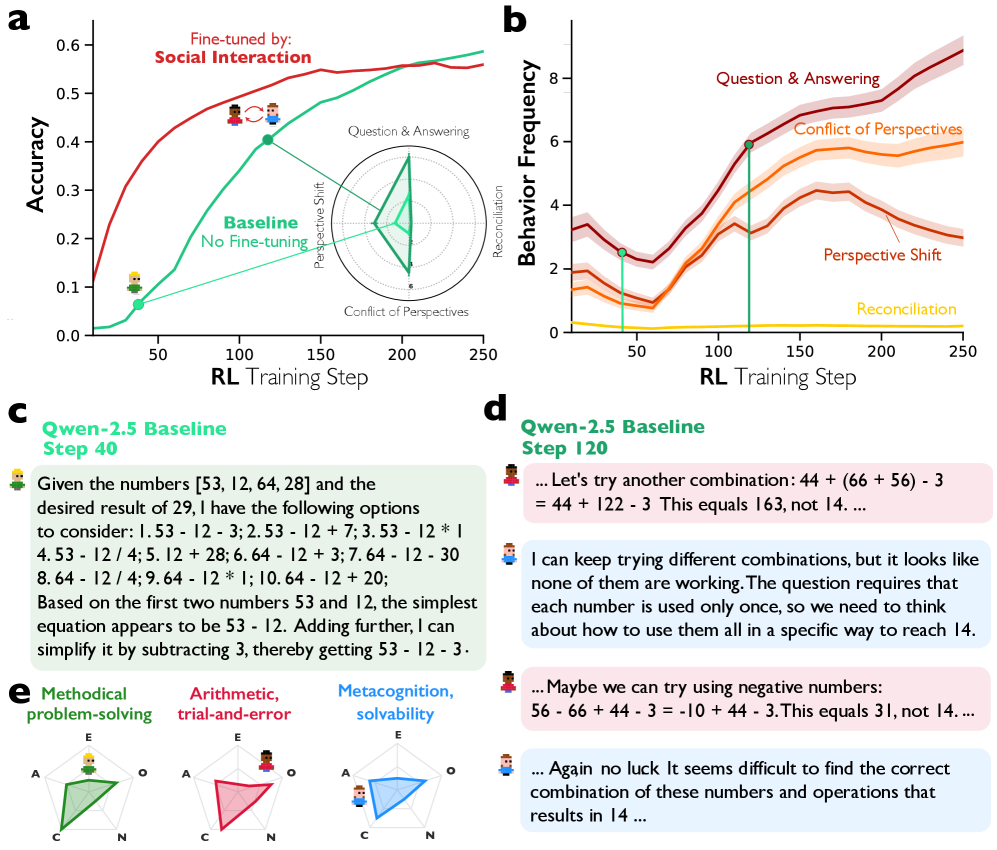

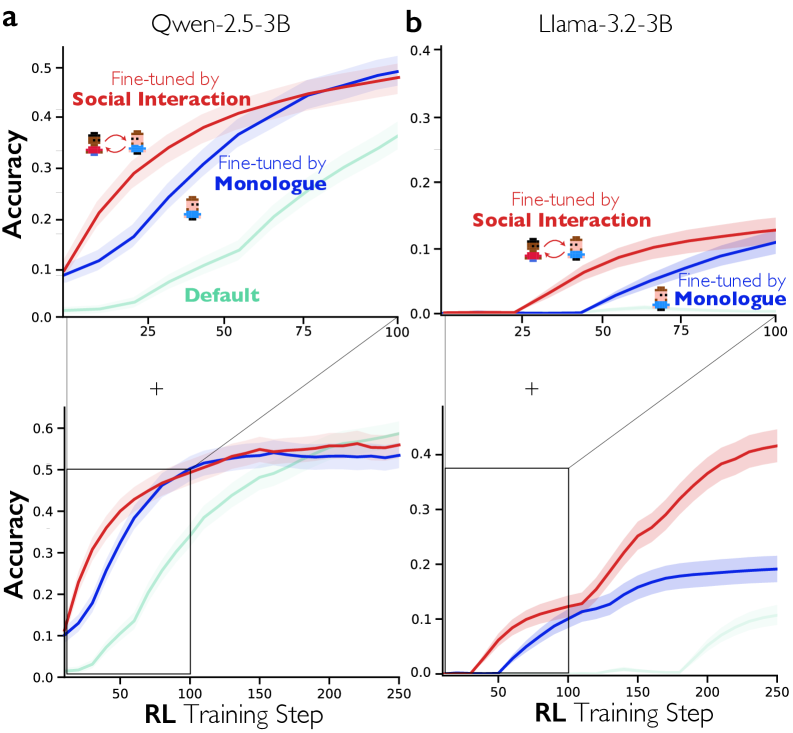

We first examine whether conversational behaviours spontaneously increase despite not being directly rewarded. Fig. 4a presents the results, showing that accuracy improves substantially over training, rising from near zero at baseline to approximately 58% by step 250. Fig. 4b reveals that the frequency of conversational behaviours—particularly Question & Answering and Conflict of Perspectives—rise throughout training despite receiving no direct reward. Perspective shifts also increase until approximately step 160, although they start to decrease as the model becomes able to reach answers with fewer shifts across the training phase. Fig. 4c-d illustrate this qualitative shift: at step 40, the model produces mechanical, enumerative chain-of-thought-style reasoning, whereas by step 120, two distinctive simulated personas have appeared, recognizing their collectivity with the pronoun “we”—expressing uncertainty (“Again no luck”), considering alternatives (“Maybe we can try using negative numbers”), and reflecting on problem constraints. As shown in Fig. 4e, these behaviours occur while the model employs two distinct personas according to LLM-as-judge evaluation: a methodical problem-solver high in Conscientiousness and low in Openness, and an exploratory trial-and-error thinker high in Openness and Extraversion, with metacognitive reflection on solvability—marked by Neuroticism—mediating between the two. Similar to our earlier findings based on sparse autoencoders, the increase of these behaviours has co-occurred with the increase of other cognitive behaviours, such as verification and backtracking (Extended Data Fig. 7).

我们首先考察在没有直接奖励的情况下,对话行为是否自发增加。图 4a 展示了结果,显示准确率在训练过程中显著提高,从基线时的接近零上升到第 250 步时的约 58%。图 4b 揭示,尽管没有直接奖励,对话行为的频率——尤其是问答和观点冲突——在训练过程中持续上升。视角转换也增加,直到大约第 160 步,尽管随着模型能够在训练阶段用更少的转换次数得出答案,视角转换开始减少。图 4c-d 说明了这种定性转变:在第 40 步,模型产生的是机械的、列举式的思维链式推理,而到了第 120 步,两个独特的模拟人格已经出现,他们用代词“我们”来认识他们的集体——表达不确定性(“再次没运气”)、考虑替代方案(“也许我们可以尝试使用负数”),并反思问题约束。如图所示。 4e,这些行为发生在模型根据 LLM 作为评判者评估时采用两种不同人格时:一种是有条理的问题解决者,高责任心、低开放性,另一种是探索性的试错思考者,高开放性和外向性,同时具有元认知反思——以神经质为特征——在两者之间进行调节。类似于我们基于稀疏自编码器之前的发现,这些行为的增加与其他认知行为的增加(如验证和回溯)同时发生(扩展数据图 7)。

图 4:在奖励准确性强化学习和对话式脚手架微调下社会行为的发生情况及其影响。a,对比了使用问题解决准确性作为奖励的强化学习中,基线 Qwen-2.5-3B 模型与初始通过 Qwen-2.5-32B 生成的多智能体对话模拟社会交互进行微调的相同模型的准确性轨迹。社会初始化模型更快达到最大准确性,而基线模型最终迎头赶上,并通过采用对话行为,包括提问与回答、视角转换和视角冲突来实现。b,a 图强化学习基线模型中个体对话行为的轨迹。问答行为首先出现,随后是视角转换和冲突,它们几乎同步上升。和解行为几乎没有增加,表明个体方法相互竞争而非形成有效组合。线条使用指数移动平均(跨度=9)平滑,阴影区域表示 95%置信区间。c–d,Qwen-2.5 个基线模型在训练步骤 40 与步骤 120 时的对比。在步骤 40 时,模型主要进行线性思维链推理,而到步骤 120 时,已出现两个具有鲜明个性的模拟角色,它们通过使用代词“我们”明确地认识到自己的集体性。e,由 LLM 作为评判者推断出的人格特征。步骤 40 的模型表现出强烈的全能型问题解决特征,其特点为高度责任心、中等偏高的开放性和随和性、较低的外向性,以及显著较低的神经过敏性。相比之下,在步骤 120 观察到的两个协作代理显示出不同的人格特征:一个强调试错式问题解决,而另一个专门进行关于不同方法问题解决性的元认知推理。试错式代理比步骤 40 的代理外向性更低、随和性更高,而专注于问题解决性的代理则更开放,责任心显著更低。

To corroborate the role of conversational behaviours in reasoning improvement, we compare RL training under three conditions: (1) Baseline (RL only, no priming), (2) Conversation fine-tuning (supervised fine-tuning on multi-agent dialogue text before RL), and (3) Monologue fine-tuning (fine-tuning on monologue-like, step-by-step reasoning traces before RL). To generate conversational fine-tuning data, we prompt Qwen-2.5-32B-IT to produce multi-agent-like dialogues with two, three, or four distinct personas solving 8,262 reasoning tasks (see Methods: Data), and sample 600 instances that reach correct answers (500 for training, 100 for validation). In these dialogues, the model first defines distinct personas with different personality traits and expertise (e.g., <persona1> a meticulous mathematician with a strong background in number theory </persona1>, <persona2> a quick-witted and intuitive problem solver… not afraid to challenge assumptions </persona2>). These personas then engage in turn-taking dialogue where they build on, question, and correct each other’s reasoning (e.g., <think1> We can discard (2, 7) because… they are not coprime. </think1> <think2> Wait a second. We can’t discard (2, 7) just yet… they are indeed coprime because their greatest common divisor is 1. </think2> → <think1> You’re right. I overlooked that. </think1>), before converging on a final answer in <group_solution> … </group_solution>.

为验证对话行为在推理能力提升中的作用,我们比较了三种条件下的强化学习训练:(1) 基线(仅强化学习,无预训练),(2) 对话微调(在强化学习前对多智能体对话文本进行监督微调),以及(3) 独白微调(在强化学习前对类似独白的逐步推理轨迹进行微调)。为生成对话微调数据,我们提示 Qwen-2.5-32B-IT 生成包含两个、三个或四个不同角色的多智能体式对话,解决 8,262 个推理任务(参见方法:数据),并从中采样达到正确答案的 600 个实例(500 个用于训练,100 个用于验证)。在这些对话中,模型首先定义具有不同性格特征和专业知识的不同角色(例如,<persona1>一位精通数论的严谨数学家</persona1>,<persona2>一位思维敏捷、直觉敏锐的问题解决者……敢于挑战假设</persona2>)。这些角色随后进行轮流对话,相互补充、质疑和修正彼此的推理(例如,<think1>我们可以舍弃(2, 7),因为……它们不是互质的。</think1> <think2>等等。 我们暂时还不能排除(2, 7)……它们确实互质,因为它们的最大公约数是 1。</think2> → <think1> 你是对的。我疏忽了这一点。</think1>),然后最终在<group_solution>……</group_solution>中得出答案。

For monologue fine-tuning data, we generate standard chain-of-thought traces for the “same problems” with correct answers, where a single voice reasons within <think> … </think> tags (e.g., <think> Since the GCD of m and n is 8, we can express m and n as 8a and 8b respectively, where a and b are coprime… The pairs of factors of 14 are (1, 14) and (2, 7). </think>). Supplementary Table 7 presents full examples for both types of fine-tuning data. We then fine-tune Qwen-2.5-3B on these datasets using standard next-token prediction loss wherein the models learn to reproduce the full output sequence (persona definitions, turn-by-turn reasoning or monologue trace, and final answer) given only the problem as input. This priming phase familiarizes the model with conversational versus monologue formats before RL optimizes for task accuracy (see Supplementary Table 8 for SFT hyperparameters).

对于独白微调数据,我们为“相同问题”生成带有正确答案的标准思维链轨迹,其中单个声音在<think> … </think>标签内进行推理(例如,<think>由于 m 和 n 的最大公约数是 8,我们可以将 m 和 n 分别表示为 8a 和 8b,其中 a 和 b 互质……14 的因数对是(1, 14)和(2, 7)。</think>)。补充表 7 展示了这两种微调数据的完整示例。然后我们使用标准的下一个词预测损失在这些数据集上微调 Qwen-2.5-3B,其中模型学习在仅给出问题作为输入的情况下重现完整的输出序列(角色定义、逐回合推理或独白轨迹,以及最终答案)。这个预训练阶段使模型熟悉对话与独白格式,然后通过强化学习优化任务准确率(有关 SFT 超参数,请参见补充表 8)。

Extended Data Fig. 8 shows that models fine-tuned on conversational data achieve faster accuracy gains than monologue-fine-tuned models, particularly in the early stages of training. At step 40, conversation-fine-tuned Qwen-2.5-3B models reach approximately 38% accuracy while monologue-fine-tuned models remain at 28%. This pattern replicates across architectures: in Llama-3.2-3B (see Supplementary Methods: Replications on Llama-3.2-3B), the conversation-fine-tuned model reaches 11% accuracy at step 70 compared to just 5% for monologue-fine-tuned models. Interestingly, in Llama-3.2-3B, the divergence becomes more striking as training progresses. By step 150, conversation-fine-tuned Llama models achieve 40% accuracy while monologue-fine-tuned models plateau around 18%, less than half the performance. Notably, both conditions are trained on identical problems and correct answers, yet conversation-fine-tuned models consistently improve faster and reach higher asymptotic accuracy. This indicates that conversational structure itself, not merely exposure to correct solutions or task-related knowledge, drives the improvement.

扩展数据图 8 显示,在对话数据上微调的模型比在独白数据上微调的模型获得更快的准确率提升,尤其是在训练的早期阶段。在步骤 40 时,对话微调的 Qwen-2.5-3B 模型达到约 38%的准确率,而独白微调的模型仍停留在 28%。这种模式在架构中得到了复制:在 Llama-3.2-3B(参见补充方法:Llama-3.2-3B 上的复制实验),对话微调的模型在步骤 70 时达到 11%的准确率,而独白微调的模型仅为 5%。有趣的是,在 Llama-3.2-3B 中,随着训练的进行,这种差异变得更加显著。在步骤 150 时,对话微调的 Llama 模型达到 40%的准确率,而独白微调的模型则停滞在 18%左右,性能不到一半。值得注意的是,两种条件都在相同的问题和正确答案上进行训练,但对话微调的模型始终提升更快,并达到更高的渐近准确率。这表明,对话结构本身,而不仅仅是接触正确解决方案或任务相关知识,推动了这种改进。

We further test whether conversational scaffolding transfers across domains. Models fine-tuned on multi-agent dialogues for the Countdown task are evaluated on a qualitatively different task: political misinformation detection, where models discriminate between true and fabricated headlines from 23,299 fact-checked claims from PolitiFact. Despite never encountering this domain during fine-tuning, conversation-primed models achieve faster accuracy gains than baseline models (see Supplementary Methods: Cross-domain reasoning transfer and Extended Data Fig. 9). Together, these results suggest that conversational structure facilitates the emergence of reasoning strategies during RL.

我们进一步测试了对话支架是否能在不同领域间迁移。在 Countdown 任务的多智能体对话上微调的模型,在评估一个性质上不同的任务:政治虚假信息检测,该任务要求模型从 PolitiFact 提供的 23,299 条经过事实核查的声明中区分真实和编造的标题。尽管在微调期间从未接触过这个领域,对话预训练的模型比基线模型实现了更快的准确率提升(参见补充方法:跨领域推理迁移和扩展数据图 9)。这些结果共同表明,对话结构促进了在强化学习过程中推理策略的涌现。

Discussion 讨论

Our findings suggest that reasoning models like DeepSeek-R1 do not simply generate longer or more elaborate chains of thought. Rather, they exhibit patterns characteristic of a social and conversational process generating “societies of thought”—posing questions, introducing alternative perspectives, generating and resolving conflicts, and coordinating diverse socio-emotional roles. These interactional patterns rarely occur in non-reasoning models across different model sizes (671B, 70B, 32B, 8B), even when controlling for reasoning trace length, suggesting that reasoning optimization introduces an intrinsic social structure within the reasoning process itself rather than merely increasing text volume. The model appears to reason by simulating internal societies, structuring thought as an exchange among interlocutors rather than as a single uninterrupted voice. The implication here is that social reasoning emerges autonomously through RL as a function of its consistent ability to produce correct answers, rather than through explicit human supervision or fine-tuning.

我们的研究发现,像 DeepSeek-R1 这样的推理模型并不仅仅生成更长或更复杂的思维链。相反,它们表现出一种社会和对话过程的模式,这种模式会生成“思维社会”——提出问题、引入不同视角、产生和解决冲突,以及协调多样的社会情感角色。这些互动模式在不同的非推理模型(671B、70B、32B、8B)中很少出现,即使控制了推理追踪长度也是如此,这表明推理优化在推理过程中引入了内在的社会结构,而不仅仅是增加文本量。该模型似乎通过模拟内部社会来进行推理,将思维结构化为对话者之间的交流,而不是单一不间断的声音。这一启示是,社会性推理通过 RL 自主地产生,这是因为它持续地能够产生正确答案,而不是通过明确的人类监督或微调。

This structure does not appear to be merely stylistic. Conversational behaviours and socio-emotional roles are more frequently activated when DeepSeek-R1 faces more difficult problems, and they explain a substantial portion of the accuracy advantage over non-reasoning models. Steering experiments provide evidence that conversational markers are tied to reasoning performance. When we amplify a feature associated with conversational surprise—a discourse marker signaling perspective shift and constrast—accuracy on multi-step reasoning tasks doubles. Structural equation modeling reveals that conversational steering is associated with accuracy through both direct effects and indirect pathways mediated by cognitive strategies previously identified as central to reasoning, including verification, backtracking, subgoal setting, and backward chaining. This suggests that the social structure of reasoning might not be epiphenomenal but mechanistically implicated in how the model explores solution spaces and deploys effective problem-solving strategies.

这种结构似乎并不仅仅是风格上的。当 DeepSeek-R1 面对更困难的问题时,对话行为和社会情感角色会被更频繁地激活,它们解释了模型相对于非推理模型的准确率优势的大部分。转向实验提供了证据,表明对话标记与推理性能相关。当我们增强与对话惊讶相关的特征——一个指示视角转换和对比的语篇标记——多步推理任务的准确率会翻倍。结构方程模型揭示,对话转向通过直接效应和间接路径(这些路径由先前被识别为推理核心的认知策略所中介,包括验证、回溯、子目标设定和反向链接)与准确率相关。这表明,推理的社会结构可能并非伴随现象,而是机制性地涉及模型探索解决方案空间和部署有效问题解决策略的方式。

We further find that this interactional organization is supported by diversity among multiple implicit “voices” within reasoning traces. These voices vary systematically in personality traits and domain expertise, and mechanistic interpretability analyses corroborate that models activate more diverse personality- and expertise-related features when steered toward conversational markers. This pattern suggests that findings from human team research—where diversity in socially oriented traits such as extraversion and neuroticism enhances collective performance, whereas diversity in task-oriented traits such as conscientiousness can impair coordination and efficiency21, 65—may offer a useful lens for interpreting language models’ collective reasoning behaviours. Most R1 reasoning personas were surprisingly disciplined and hard-working!

我们进一步发现,这种交互组织得到了推理轨迹中多个隐含“声音”之间多样性的支持。这些声音在人格特质和领域专业知识上存在系统差异,而机制可解释性分析证实,当模型被引导至对话标记时,会激活更多与人格和专业知识相关的特征。这种模式表明,人类团队研究中的发现——在社会导向特质(如外向性和神经质)的多样性会提升集体表现,而在任务导向特质(如责任心)的多样性会损害协调性和效率——可能为解释语言模型的集体推理行为提供了一个有用的视角。大多数 R1 推理角色出人意料地自律且勤奋!

Reinforcement learning (RL) experiments further support the functional role of conversational structure. Models fine-tuned on multi-agent dialogues learn to reason more effectively than models fine-tuned only on correct, monologue-like reasoning traces. The benefit therefore lies not in the correctness of initial reasoning but in the procedural scaffolding provided by conversational organization. Although these experiments used relatively small 3B-parameter models (Qwen-2.5-3B and Llama-3.2-3B) on simple arithmetic tasks and misinformation detection tasks, the results suggest that even minimal social structuring within reasoning traces can accelerate the emergence of generalizable reasoning behaviour.

强化学习(RL)实验进一步支持了对话结构的职能作用。在多智能体对话上微调的模型比仅在正确的、类似独白的推理轨迹上微调的模型更能有效地进行推理。因此,这种优势不在于初始推理的正确性,而在于对话组织提供的程序性支架。尽管这些实验使用了相对较小的 3B 参数模型(Qwen-2.5-3B 和 Llama-3.2-3B),在简单的算术任务和虚假信息检测任务上,但结果表明,即使在推理轨迹中存在最小的社会结构,也能加速通用推理行为的出现。

Collectively, these findings suggest the benefits of studying “social scaling” in reasoning-optimized models. As their test-time computations expand, reasoning traces evolve from isolated monologues into structured dialogues among differentiated internal perspectives. High-performing reasoning thus seems to depend on how attention, role-taking, and conflict resolution are coordinated within emergent “societies of thought.” Our goal is not to take sides on whether reasoning model traces should be regarded as discourse among simulated human groups or a computational mind’s simulation of such discourse. Indeed, as we note above, even this distinction becomes fundamentally unclear as some theories of cognition posit how mature individual minds develop from simulations of multi-agent interaction. Nevertheless, alignments between our findings on successful reasoning models and prior literature on successful human teams (e.g., diverse personality traits lead to successful collaborations) suggest that principles governing effective group collaboration may offer valuable insights for interpreting and engineering reasoning behaviours in language models. This perspective extends long-standing research on human team collaboration, where group composition and diversity are known to shape collective intelligence through variations in personality and expertise16, 17, 18, 19, 11, 20, 21 . Analogous dynamics within AI systems remain largely unexplored. Early investigations of human–AI collaboration70 have begun to characterize this emerging domain, but how diversity and coordination operate within the reasoning traces of large language models remains an open question. DeepSeek-R1’s and QwQ’s internal reasoning patterns suggest that such models may already self-organize a productive heterogeneity of perspectives, implying that diversity could be as fundamental to artificial reasoning as it is to human collaboration and collective dominance.

这些发现共同表明,研究推理优化模型中的“社会规模”具有益处。随着它们在测试时的计算扩展,推理轨迹从孤立的独白演变为不同内部视角之间的结构化对话。因此,高性能的推理似乎取决于在涌现的“思想社会”中如何协调注意力、角色扮演和冲突解决。我们的目标不是判断推理模型轨迹是否应该被视为模拟人类群体之间的对话,或是计算心智对这种对话的模拟。事实上,正如我们上述所述,即使这种区分也随着一些认知理论提出成熟个体心智如何从多智能体交互模拟中发展而来而变得根本性模糊。然而,我们关于成功推理模型的研究发现与先前关于成功人类团队的文献(例如,多样的人性特质导致成功的合作)之间的契合表明,有效群体协作的治理原则可能为解释和设计语言模型中的推理行为提供有价值的见解。 这一视角延续了关于人类团队协作的长期研究,其中团队构成和多样性通过人格和专长上的差异塑造集体智能 16, 17, 18, 19, 11, 20, 21 。人工智能系统内部的类似动态仍基本未被探索。早期关于人机协作 70 的研究开始描述这一新兴领域,但多样性和协调如何在大型语言模型的推理轨迹中运作仍是一个悬而未决的问题。DeepSeek-R1 和 QwQ 的内部推理模式表明,这类模型可能已经自我组织起一种富有成效的视角异质性,这意味着多样性对于人工智能推理而言,可能和它对于人类协作和集体主导一样根本。

A growing trend in AI involves agentic architectures that deploy multiple agents engaged in more complex configurations than single-channel debate, including hierarchy, complex networks and even entire institutions of interacting agents71, 72, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 34. Our work suggests the importance of exploring alternative structures, but also inhabiting them with diverse perspectives, personalities, and specialized expertise that drive complementarity and collective success in the human social world. Understanding how diversity and social scaffolding interact could shift how we conceptualize large language models, from solitary problem-solving entities toward collective reasoning architectures, where intelligence arises not merely from scale but the structured interplay of distinct voices.

人工智能领域的一个日益增长的趋势是采用多智能体架构,这些智能体在比单通道辩论更复杂的配置中运作,包括层级结构、复杂网络,甚至整个由交互智能体组成的机构 71, 72, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 34 。我们的研究表明探索替代结构的重要性,但也需要用多样化的视角、个性和专业领域来充实这些结构,这些因素在人类社会中驱动互补性和集体成功。理解多样性和社会支架如何相互作用,可能会改变我们如何概念化大型语言模型,从孤独的解决问题实体转变为集体推理架构,其中智能不仅源于规模,更源于不同声音的结构化互动。

Methods 方法

Data 数据

We generate chains of thought and final answers for 8,262 reasoning problems spanning symbolic logic, mathematical problem solving, scientific reasoning, instruction following, and multi-agent inference. The benchmark suite includes BigBench Hard (BBH) tasks requiring multi-step logical inference, reference tracking, and compositional reasoning; GPQA (Graduate-level Physics Question Answering) for graduate-level STEM reasoning; MATH (Hard) subset for multi-step derivations across algebra, geometry, probability, and number theory; MMLU-Pro for advanced conceptual knowledge; IFEval for instruction-following consistency; and MUSR (Mathematics Understanding and Symbolic Reasoning) for symbolic manipulation and structured mathematical reasoning (see Supplementary Table 9 for details).

我们为涵盖符号逻辑、数学问题解决、科学推理、指令遵循和多智能体推理的 8,262 个推理问题生成了思维链和最终答案。基准测试套件包括需要多步逻辑推理、引用跟踪和组合推理的 BigBench Hard (BBH)任务;用于研究生级 STEM 推理的 GPQA(研究生级物理问答);用于代数、几何、概率和数论等多步推导的 MATH(难)子集;用于高级概念知识的 MMLU-Pro;用于指令遵循一致性的 IFEval;以及用于符号操作和结构化数学推理的 MUSR(数学理解和符号推理)(详情请参见补充表 9)。

We generate responses using six models: two reasoning models—DeepSeek-R1-0528 (671B parameters) and QwQ-32B—and four instruction-tuned models—DeepSeek-V3-0324 (671B parameters), Qwen-2.5-32B-Instruct, Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct, and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct—under a zero-shot setting. DeepSeek-V3 is the instruction-tuned model based on DeepSeek-V3-Base from which DeepSeek-R1 is derived through reinforcement learning, and Qwen-2.5-32B-Instruct is the instruction-tuned model based on Qwen-2.5-32B from which QwQ-32B is derived. For brevity, we refer to these models as DeepSeek-R1, QwQ-32B, DeepSeek-V3, Qwen-2.5-32B-IT, Llama-3.3-70B-IT, and Llama-3.1-8B-IT, respectively. We set the temperature to 0.6, a temperature recommended for standard reasoning tasks4.

我们使用六个模型生成响应:两个推理模型——DeepSeek-R1-0528(671B 参数)和 QwQ-32B,以及四个指令微调模型——DeepSeek-V3-0324(671B 参数)、Qwen-2.5-32B-Instruct、Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct 和 Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct——在零样本设置下。DeepSeek-V3 是基于 DeepSeek-V3-Base 的指令微调模型,DeepSeek-R1 通过强化学习从 DeepSeek-V3-Base 衍生而来;Qwen-2.5-32B-Instruct 是基于 Qwen-2.5-32B 的指令微调模型,QwQ-32B 从 Qwen-2.5-32B 衍生。为简洁起见,我们将这些模型分别称为 DeepSeek-R1、QwQ-32B、DeepSeek-V3、Qwen-2.5-32B-IT、Llama-3.3-70B-IT 和 Llama-3.1-8B-IT。我们将温度设置为 0.6,这是标准推理任务推荐的温度 4 。

Measurements 测量

Conversational Behaviours

对话行为