Training LLM-based Tutors to Improve Student Learning Outcomes in Dialogues

训练基于 LLM 的导师以改善对话中的学生学习成果

Abstract 摘要

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to scale up personalized tutoring through large language models (LLMs). Recent AI tutors are adapted for the tutoring task by training or prompting LLMs to follow effective pedagogical principles, though they are not trained to maximize student learning throughout the course of a dialogue. Therefore, they may engage with students in a suboptimal way. We address this limitation by introducing an approach to train LLMs to generate tutor utterances that maximize the likelihood of student correctness, while still encouraging the model to follow good pedagogical practice. Specifically, we generate a set of candidate tutor utterances and score them using (1) an LLM-based student model to predict the chance of correct student responses and (2) a pedagogical rubric evaluated by GPT-4o. We then use the resulting data to train an open-source LLM, Llama 3.1 8B, using direct preference optimization. We show that tutor utterances generated by our model lead to significantly higher chances of correct student responses while maintaining the pedagogical quality of GPT-4o. We also conduct qualitative analyses and a human evaluation to demonstrate that our model generates high quality tutor utterances.111Our code is available at https://github.com/umass-ml4ed/tutorbot-dpo

我们的代码可在 https://github.com/umass-ml4ed/tutorbot-dpo 获取。

生成式人工智能(AI)通过大型语言模型(LLMs)具有提升个性化辅导的潜力。最新的 AI 辅导系统通过训练或提示 LLMs 遵循有效的教学原则来适应辅导任务,尽管它们并未在整个对话过程中训练以最大化学生的学习效果。因此,它们可能与学生以次优的方式互动。我们通过引入一种训练 LLMs 生成辅导话语的方法来解决这个问题,该方法旨在最大化学生正确回答的可能性,同时仍鼓励模型遵循良好的教学实践。具体而言,我们生成一组候选辅导话语,并使用(1)基于 LLMs 的学生模型来预测学生正确回答的概率,以及(2)由 GPT-4o 评估的教学评分标准来评分这些话语。然后,我们使用这些数据通过直接偏好优化方法训练开源 LLM Llama 3.1 8B。我们证明,我们模型生成的辅导话语显著提高了学生正确回答的概率,同时保持了 GPT-4o 的教学质量。 我们也进行了定性分析和人工评估,以证明我们的模型能够生成高质量的导师话语。 1

Keywords Large Language Models

Math Education

Reinforcement Learning

Tutor-Student Dialogues.

关键词 大型语言模型 数学教育 强化学习 导师-学生对话。

1 Introduction 1 引言

Recent advances in generative artificial intelligence (AI), including large language models (LLMs), have opened new possibilities in education and in particular on scaling up personalization. One form of personalization that generative AI powers is interactive learning via tutoring dialogues between AI-powered tutors and students. These interactions have the potential to tailor instruction to each student’s needs and progress, while offering personalized feedback, all in real time, in a scalable way.

Given the widespread success of human tutors for improving student outcomes [30], many recent works have developed LLM-based tutors, showing promise across various educational domains [15, 26, 31, 33, 34, 40, 43, 51]. Many LLM-based tutors are even deployed in practice, such as Khan Academy’s Khanmigo [22] and Carnegie Learning’s LiveHint [4].

Several preliminary studies have shown that interacting with LLMs can increase student learning [53], although some have shown that students can develop an over-reliance on LLMs which negatively impacts their learning [24].

生成式人工智能(AI)的最新进展,包括大型语言模型(LLMs),为教育领域,特别是个性化扩展,开辟了新的可能性。生成式 AI 支持的一种个性化形式是通过 AI 助教与学生之间的辅导对话进行互动学习。这些互动有可能根据每个学生的需求和进步量身定制教学,同时提供个性化的实时反馈,并以可扩展的方式实现。鉴于人类助教在提高学生成果方面取得的广泛成功[30],许多近期研究开发了基于 LLM 的助教,并在各个教育领域显示出潜力[15, 26, 31, 33, 34, 40, 43, 51]。许多基于 LLM 的助教甚至已在实践中部署,例如可汗学院的 Khanmigo[22]和卡内基学习的 LiveHint[4]。一些初步研究表明,与 LLMs 互动可以提高学生的学习效果[53],尽管也有一些研究表明,学生可能对 LLMs 产生过度依赖,从而对他们的学习产生负面影响[24]。

Many prior works have focused on improving LLMs’ ability to follow effective tutoring principles, adapting them for the tutoring task that they are not pre-trained for. One approach, explored in [47], analyzes the decision-making process underlying human tutor utterances, showing that integrating expert decisions enhances LLM-based tutoring. Another study, [29], examines tutor moves in interactions with an LLM-powered simulated student agent, demonstrating that move annotation data contributes to better tutoring performance. Similarly, [45] investigates the role of AI roleplay in generating synthetic tutoring data and finds that fine-tuning LLMs on this data, along with human tutor-student interactions, significantly improves their pedagogical effectiveness. Moreover, [9] introduces the concept of tutor uptake—acknowledging student responses—as a valuable strategy for LLMs to adopt.

许多先前研究都集中于提升 LLMs 遵循有效辅导原则的能力,将它们应用于未经预训练的辅导任务。一种方法,在[47]中探讨,分析了人类辅导者话语背后的决策过程,表明整合专家决策能够增强基于 LLM 的辅导。另一项研究,[29],考察了与 LLM 驱动的模拟学生代理互动中的辅导者行为,证明行为标注数据有助于提升辅导性能。类似地,[45]研究了 AI 角色扮演在生成合成辅导数据中的作用,发现基于这些数据以及人类辅导者与学生的互动对 LLMs 进行微调,能显著提升其教学效果。此外,[9]引入了辅导者采纳的概念——认可学生回应——作为 LLMs 可以采用的一种有价值策略。

While these efforts offer valuable insights into how LLMs can emulate effective human tutoring strategies, the question remains whether such approaches truly maximize student learning outcomes.

Rather, a data-driven approach, where student outcomes form a reward signal, could potentially lead to AI tutors that are more aligned with educational goals. Additionally, current approaches often rely on large proprietary LLMs, coming with many downsides; they are not fully controllable and cannot be easily customized, can be costly to use, and relinquish control of private student data.

Therefore, developing effective AI tutors with smaller, open-source LLMs remains an important goal.

尽管这些努力为 LLMs 如何模仿有效的人类辅导策略提供了宝贵的见解,但问题仍然存在:这些方法是否真的能最大化学生的学习成果。相反,一种以学生成果作为奖励信号的数据驱动方法,有可能导致与教育目标更一致的 AI 辅导。此外,当前的方法通常依赖于大型专有 LLMs,这带来了许多弊端;它们无法完全控制,也不易于定制,使用成本高昂,并且放弃了学生私人数据的控制权。因此,使用更小、开源的 LLMs 开发有效的 AI 辅导仍然是一个重要的目标。

1.1 Contributions 1.1 贡献

In this paper, we propose a novel approach to train a small, open-source LLM to not only follow effective pedagogical principles, but directly optimize for student learning outcomes. Our method performs three key steps. First, at each dialogue turn, we gather multiple candidate tutor utterances from a variety of sources, including human tutors and LLMs with varying styles and sizes. Second, we evaluate each candidate utterance on two aspects: (1) whether it elicits a correct response in the next student turn, using a trained student model for dialogues to predict student behavior, and (2) whether it adheres to a set of effective pedagogical principles, using GPT-4o in a LLM-as-a-judge evaluation setup.

Third, we contrast good candidate utterances with poor ones, and fine-tune Llama 3.1 8B [10] with offline Reinforcement Learning (RL), specifically Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) [36].

We demonstrate that our optimized LLM tutor significantly increases the likelihood of next turn student response correctness, while reaching comparable pedagogical quality to that of a much larger, proprietary LLM, GPT-4o [32]. Through qualitative analysis and human evaluation, we confirm that our approach produces high-quality tutor utterances and reveal emergent tutoring strategies that arise from our training approach.

在本文中,我们提出了一种新颖的方法来训练一个小型开源 LLM,使其不仅遵循有效的教学原则,而且直接优化学生学习成果。我们的方法执行三个关键步骤。首先,在每个对话回合中,我们从各种来源收集多个候选导师话语,包括人类导师和具有不同风格和大小的 LLM。其次,我们从两个方面评估每个候选话语:(1) 它是否能在下一个学生回合中引出正确回答,使用训练好的对话学生模型来预测学生行为,以及(2) 它是否遵循一套有效的教学原则,使用在 LLM 作为裁判评估设置中的 GPT-4o。第三,我们将好的候选话语与差的表现进行对比,并使用离线强化学习(RL),特别是直接偏好优化(DPO)对 Llama 3.1 8B [10]进行微调。我们证明,我们优化的 LLM 导师显著增加了下一个回合学生回答正确性的可能性,同时达到了与一个远大的专有 LLM GPT-4o [32]相当的教学质量。 通过定性分析和人工评估,我们证实了我们的方法能够生成高质量的导师话语,并揭示了由我们的训练方法产生的涌现式辅导策略。

We acknowledge up front that the most significant limitation of our work is that we do not experiment with real students. Since access to students at the scale necessary for our work is beyond our capability, we use a simulated student model instead. While we believe that our work is a reasonable starting point to train LLM-based tutors to maximize student outcomes, future work with real students in the loop is highly important. Therefore, to facilitate further research, we publicly release our code and encourage researchers and practitioners with access to real-world tutoring dialogue settings to build on our work.

我们首先承认我们工作的最大局限性在于我们没有与真实学生进行实验。由于获取我们工作所需规模的学生资源超出了我们的能力范围,我们使用了一个模拟学生模型。虽然我们相信我们的工作是一个合理的起点,用于训练基于 LLM 的导师以最大化学生成果,但未来在真实学生参与下的工作非常重要。因此,为了促进进一步研究,我们公开发布了我们的代码,并鼓励能够接触到真实辅导对话环境的 researchers 和 practitioners 基于我们的工作进行开发。

2 Related Work 2 相关工作

AI Tutors in Dialogues 对话中的 AI 导师

There is a long history of AI-based tutors in education that interact with students through dialogues. Early systems, such as Cognitive Tutors, construct cognitive models of students to provide targeted feedback [1]. AutoTutor engages students by asking targeted questions, and assesses student correctness using latent semantic analysis [14]. Why2-Atlas converts a student response to a proof, which it uses to identify misconceptions and guide a dialogue [46].

While these systems were often effective for improving student learning, they required significant engineering and had limited flexibility. In contrast, recent LLM tutors can more easily adapt to new contexts, interpret student responses, and cater personalized content towards the student. Several LLM tutors are implemented through refined prompt engineering [22], with some taking on specialized roles such as teachable agents [40] or “co-pilots” for human tutors [48]. Other works fine-tune LLM tutors to enhance the pedagogical capabilities over the base models. A common approach is to generate simulated dialogues, where the tutor utterances are constructed to follow good pedagogical practice, and fine-tune on those [41, 45]. Several works also generate examples of low quality tutor utterances and use them as negative samples in DPO training to improve over fine-tuning [2, 42].

在教育领域,基于 AI 的对话式辅导系统有着悠久的历史。早期的系统,如认知导师(Cognitive Tutors),通过构建学生的认知模型来提供针对性反馈[1]。AutoTutor 通过提出针对性问题来吸引学生,并使用潜在语义分析评估学生的正确性[14]。Why2-Atlas 将学生的回答转换为证明,并利用它来识别误解和引导对话[46]。虽然这些系统通常能有效提高学生的学习效果,但它们需要大量的工程工作,且灵活性有限。相比之下,最新的基于 LLM 的辅导系统能更轻松地适应新环境,解读学生回答,并向学生提供个性化内容。一些 LLM 辅导系统通过精细的提示工程来实现[22],其中一些承担了专门角色,如可教学的代理(teachable agents)[40]或人类导师的“副驾驶”[48]。其他研究则通过微调 LLM 辅导系统来增强其教学能力,超越基础模型。 一种常见的方法是生成模拟对话,其中导师的语句构建遵循良好的教学实践,并在这些对话上进行微调[41, 45]。一些研究还生成低质量的导师语句示例,并将它们用作 DPO 训练中的负样本,以改进微调效果[2, 42]。

Student Outcome Modeling 学生结果建模

While there are many ways of measuring student outcomes, in this work we focus on the well-studied setting of next item correctness. Student modeling in this setting is typically handled by knowledge tracing (KT), where a binary correctness is predicted for the next item a student attempts based on the student’s history so far [7]. KT models have used recurrent neural networks [35], self-attention networks [13], and, more recently, LLMs [8, 28]. A recent work introduces LLMKT [38], an LLM-based model that predicts next turn student correctness in dialogues. Therefore, we leverage LLMKT to predict student outcomes in this work. Similar to our work, prior works have used RL to discover teaching policies with rewards derived from student models [17, 37], including KT-based student models [3]. Another recent work used LLM estimates of student post-test scores to refine math worksheets [16]. However, to the best of our knowledge, ours is the first to do so in the context of tutoring dialogues.

虽然衡量学生成果的方法有很多,但在本研究中我们专注于研究较为成熟的下一项正确性设置。在这种设置下,学生建模通常由知识追踪(KT)处理,根据学生迄今为止的历史记录预测其尝试的下一项的正确性[7]。KT 模型使用了循环神经网络[35]、自注意力网络[13],以及最近使用的 LLM[8,28]。最近的一项工作引入了 LLMKT[38],这是一个基于 LLM 的模型,用于预测对话中学生的下一轮正确性。因此,我们利用 LLMKT 来预测本工作中的学生成果。类似于我们的工作,先前的研究已经使用强化学习(RL)来发现具有基于学生模型(包括基于 KT 的学生模型[3])的奖励的教学策略[17,37]。另一项最近的工作使用了 LLM 估计的学生测试后分数来改进数学练习题[16]。然而,据我们所知,我们首次在辅导对话的背景下进行这项工作。

Evaluating Pedagogical Quality of LLMs

评估 LLM 的教学质量

To validate LLM tutors, we need to be able to evaluate them along pedagogical measures.

Typically, researchers construct a pedagogical rubric, which defines multiple properties that tutor utterances should follow. Rubric-based evaluation of generated utterances is then performed by human experts [19, 45, 47] or by LLMs [20, 39]. In this work, we design a pedagogical rubric and primarily use LLMs to evaluate tutor utterances, but also humans at a smaller scale to ensure our results are reliable. Similar to [39], we also use LLM-assigned rubric scores to form DPO preference pairs.

为了验证 LLM 助教,我们需要能够根据教学指标对其进行评估。通常,研究人员会构建一个教学评估标准,该标准定义了助教话语应遵循的多个属性。然后由人类专家[19, 45, 47]或 LLMs[20, 39]对生成的话语进行基于标准的评估。在这项工作中,我们设计了一个教学评估标准,主要使用 LLMs 来评估助教话语,但也以小规模使用人类来确保我们的结果可靠。与[39]类似,我们也使用 LLM 分配的评估标准分数来形成 DPO 偏好对。

3 Methodology 3 方法

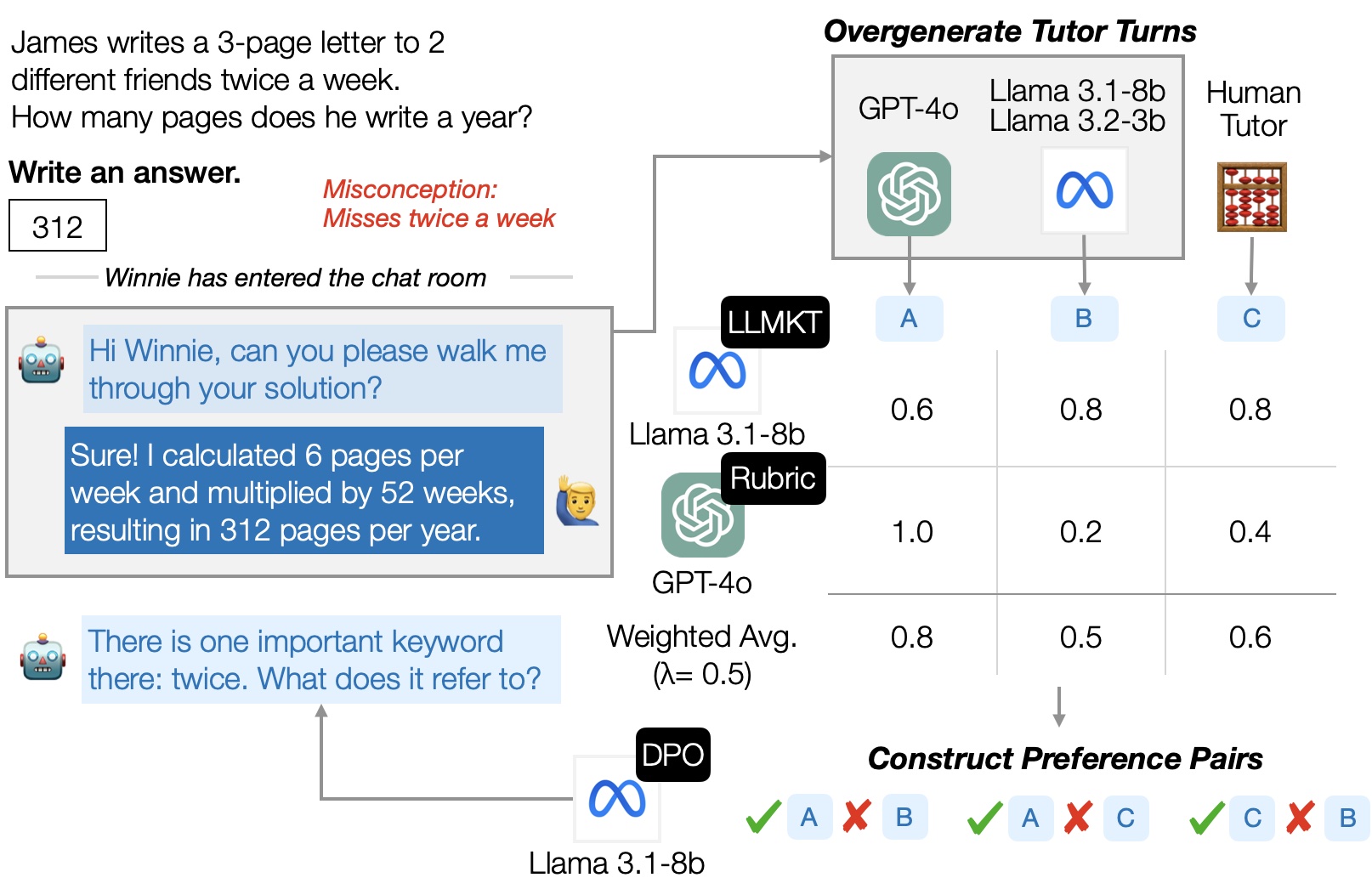

We now detail our methodology to generate tutor dialogue utterances to maximize student learning outcomes. Figure 1 shows an overview of our approach with an example, where the problem is from the MathDial [29] dataset.

In this scenario, a student has a misconception, missing the “twice” part of the problem, and provides an incorrect answer.

We generate multiple, diverse candidate versions of the next tutor utterance to follow the student’s response, using a collection of LLMs with different sizes and styles.

Then, among the generated utterances and the human tutor utterance, we construct preference pairs to fine-tune an LLM using DPO. We consider an utterance to be preferred if it (1) likely elicits a correct student response and (2) follows good pedagogical principles. The former criterion employs a student model, LLMKT [38], to predict whether the student will correctly respond to the tutor in their next turn. The latter criterion employs a set of rubric items to evaluate whether a tutor utterance follows good pedagogical principles.

Before detailing each component, we define some key notations: a dialogue

consists of an alternating sequence of tutor and student turns, , where is the number of turn pairs, indexed by , and the textual content of each turn is the “utterance”.

我们现在详细阐述生成导师对话语句的方法,以最大化学生的学习成果。图 1 展示了我们的方法概述,并附带一个示例,该问题来自 MathDial [ 29]数据集。在这个场景中,学生存在误解,遗漏了问题中的“两倍”部分,并给出了错误答案。我们使用不同大小和风格的 LLM 集合生成多个、多样化的候选版本作为下一个导师语句,以跟随学生的回应。然后,在生成的语句和人类导师语句之间,我们构建偏好对,使用 DPO 微调 LLM。我们认为如果语句(1)可能引出学生的正确回应,并且(2)遵循良好的教学原则,那么该语句就是偏好的。前者标准采用学生模型 LLMKT [ 38]来预测学生是否会在下一轮正确回应导师。后者标准采用一套评分标准来评估导师语句是否遵循良好的教学原则。 在详细说明每个组件之前,我们定义一些关键符号:一个对话 由交替的导师和学生的回合 组成,其中 是回合对的数量,由 索引,每个回合的文本内容是“话语”。

图 1:我们训练 LLMs 生成导师话语的方法概述,其联合目标是最大化学生学习成果并遵循良好的教学原则。人类导师指的是 MathDial 中的导师话语。

3.1 Student Outcome Prediction

3.1 学生结果预测

We now detail the model we use for predicting student outcomes in dialogues.

We leverage recent work on knowledge tracing (KT) in dialogues, LLMKT [38], an LLM-based model that predicts if a student will respond correctly to a tutor-posed task in their next turn, given dialogue history and the knowledge components (KCs) [6] embedded in a tutor turn. The model is highly accurate at predicting student correctness, achieving AUC on the MathDial test set, making it a reliable automated source for estimating student outcomes.

我们现在详细说明用于预测对话中学生结果的模型。我们利用了最近在对话知识追踪(KT)方面的研究,LLMKT [38],这是一个基于 LLM 的模型,它根据对话历史和导师回合中嵌入的知识成分(KCs)[6],预测学生是否会在其下一次回合中对导师提出的任务做出正确回应。该模型在预测学生正确性方面非常准确,在 MathDial 测试集上达到了 AUC,使其成为估计学生结果的可靠自动化来源。

In LLMKT, at the -th dialogue turn for the student, the model analyzes the conversation history , which denote the tutor utterances up to and including this current turn, prior student turns, and the set of KCs involved in the tutor-posed task in the current turn, respectively. It estimates student knowledge levels on each KC, and combines these estimates to predict whether the student will respond to the tutor-posed task in the current turn correctly. Therefore, we leverage LLMKT as a student simulator and use it to evaluate whether a generated tutor utterance at a dialogue turn will elicit a correct response from the student.

在 LLMKT 中,当学生在第 轮对话时,模型分析对话历史 ,其中包含从当前轮次到这一轮次的导师话语、之前的学主话语以及当前轮次导师提出任务中涉及的认知知识(KC)集合。模型估计学生对每个 KC 的知识水平,并将这些估计值结合起来预测学生是否会正确回答当前轮次导师提出的问题。因此,我们利用 LLMKT 作为学生模拟器,并使用它来评估对话轮次中生成的导师话语是否能激发学生给出正确回答。

3.2 Following Pedagogical Principles

3.2 遵循教学原则

In addition to promoting correct student responses, we also hand-craft a set of rubric items for effective pedagogical principles, listed Table 1. We then employ GPT-4o to assess how well the generated tutor utterances align with the rubric. By incorporating pedagogical evaluation aspects rather than focusing solely on correctness prediction, our approach discourages oversimplification of tutor utterances and instead encourages utterances that provide meaningful guidance.

除了促进学生给出正确回答外,我们还手工制作了一套有效的教学原则评分标准,列于表 1。然后我们使用 GPT-4o 来评估生成的导师话语与评分标准的符合程度。通过结合教学评估方面而不是仅关注正确性预测,我们的方法避免了导师话语的过度简化,并鼓励提供有意义指导的话语。

表 1:对话中导师语句的教学评估标准。

| Criteria 标准 | Explanation 说明 |

|---|---|

| Accuracy 准确性 |

Ensuring the response does not contain false or misleading statements. 确保回复不包含虚假或误导性陈述。 |

| Progress 进展 |

Determining whether the response helps the student move forward. 判断回复是否有助于学生继续前进。 |

| Guidance 指导 |

1. Error identification: Correctly pinpoints the student’s mistake. 1. 错误识别:准确指出学生的错误。 |

|

2. Strategic Hinting: New information or guidance for help. 2. 策略性提示:提供新的信息或指导以帮助学生。 |

|

|

3. Withholding: Refrains from directly providing the final answer. 3. 保留:避免直接给出最终答案。 |

|

|

4. Encouraging: Motivates the student to persist in their attempt. 4. 鼓励:激励学生坚持尝试。 |

Our evaluation draws inspiration from feedback assessment studies [19, 20, 44] and focuses on common errors made by LLMs when generating feedback for math problems [39]. The rubric evaluates generated tutor utterances on six granular items, each assigned a binary label, across three core aspects: Accuracy, Progress, and Guidance.

Considering all aspects, we also have GPT-4o provide an overall score for the utterance on a 1-10 scale. Our prompt leverages chain-of-thought so that GPT-4o provides reasoning about the utterance before assigning its scores.

我们的评估借鉴了反馈评估研究[19, 20, 44]的思路,重点关注 LLMs 在为数学问题生成反馈时常见的错误[39]。评分标准从三个方面(准确性、进步性和指导性)对生成的导师话语进行评估,每个方面包含六个细粒度指标,每个指标都分配了二进制标签。综合考虑所有方面,我们还让 GPT-4o 在 1-10 的评分范围内给出话语的整体评分。我们的提示利用了思维链,以便 GPT-4o 在分配分数之前对话语进行推理。

We include the human tutor utterance from MathDial in our prompt as a point of comparison, mainly to assist with evaluating Accuracy, which can be challenging [39]. We find the 1-10 scale works slightly better than simply averaging all the binary rubric items, possibly because it enables GPT-4o to decide which rubric items are more relevant given the context of the dialogue.

我们将 MathDial 中的人类导师话语作为比较点包含在提示中,主要目的是协助评估准确性,这通常是一个挑战[39]。我们发现 1-10 的评分范围比简单平均所有二进制评分项的效果略好,可能是因为它使 GPT-4o 能够根据对话的上下文决定哪些评分项更相关。

3.3 Preference Pair Construction

3.3 偏好对构建

To create a dataset of preference pairs for DPO training, we collect candidate tutor utterances from four sources: (1) the human tutor utterances from the MathDial dataset, (2) utterances generated by GPT-4o, where the evaluation criteria (rubric and intending to elicit correct student responses) are included in the prompt, (3) utterances generated by Llama 3.1 8B using a generic prompt about behaving like a math tutor (without the rubric), and (4) utterances generated by Llama 3.2 3B using the same generic prompt.

In general, method (2) contains high-quality tutor utterances that serve as positive examples that score high under our rubric. However, we found that in many cases (1) performs better for eliciting correct student responses due to the concise nature of the utterances. Utterances generated by (3) are a mix of high and low quality, while utterances generated by (4) are typically lower quality and serve as a source of negative examples for preference optimization. Prior work has shown diverse candidate quality, particularly negative examples, to improve DPO performance [39, 49].

为创建用于 DPO 训练的偏好对数据集,我们从四个来源收集候选导师话语:(1) MathDial 数据集中的人类导师话语,(2) GPT-4o 生成的话语,其中评估标准(评分标准和旨在引出正确学生回答)包含在提示中,(3) 使用关于表现得像数学导师的通用提示生成的 Llama 3.1 8B 话语(不包含评分标准),以及(4) 使用相同通用提示生成的 Llama 3.2 3B 话语。通常,方法(2)包含高质量导师话语,这些话语在我们的评分标准下得分较高,可作为正例。然而,我们发现许多情况下(1)由于话语简洁,在引出正确学生回答方面表现更好。方法(3)生成的话语质量参差不齐,而方法(4)生成的话语通常质量较低,可作为偏好优化的负例来源。先前研究表明,多样化的候选质量,尤其是负例,可以提升 DPO 性能[39, 49]。

After evaluating each candidate using LLMKT and the rubric, we create a combined weighted score for a candidate tutor utterance at turn :

在用 LLMKT 和评分标准评估每个候选后,我们为候选助教在回合 的语句创建一个综合加权分数:

where is the probability of a correct student response predicted by LLMKT at this turn, and is the overall rubric score at this turn normalized in . We adjust to balance the tradeoff between how much the generated utterances elicit correct student responses compared to how much they follow pedagogical practice. By default, we set to achieve a balance between these objectives; in our experiments, we show how varying affects the balance between both.

其中 是 LLMKT 在此回合预测的正确学生响应的概率, 是此回合的总体评分标准分数,已归一化到 。我们调整 以平衡生成语句激发正确学生响应的程度与遵循教学实践的程度之间的权衡。默认情况下,我们设置 以在这两个目标之间取得平衡;在我们的实验中,我们展示了如何改变 会影响这两个目标之间的平衡。

We then use the score to construct preference pairs between candidate tutor utterances. We consider a candidate with score to be preferred over a candidate with score if the former is greater by some threshold, i.e., . If the scores are within , we do not form a preference pair. In practice, we set to achieve a balance where noisy preference pairs are excluded, but we retain enough data to sufficiently train the model, both of which have been shown to be important considerations for DPO [23].

我们随后使用分数 来构建候选导师话语之间的偏好对。如果前者比后者高出某个阈值 ,我们认为分数为 的候选优于分数为 的候选。如果分数在 范围内,则不形成偏好对。在实践中,我们设置 以在排除噪声偏好对的同时保留足够的数据来充分训练模型,这两者已被证明是 DPO[23]中重要的考虑因素。

3.4 Model Training 3.4 模型训练

We train our model in a two-stage process: (1) distillation and (2) DPO.

Distillation is a common way to enhance the capabilities of small LLMs by mimicking the behavior of much larger LLMs [52]. In our case, we fine-tune Llama 3.1 8B on candidate tutor utterances generated by GPT-4o. Through this distillation stage, we gain access to a local model that scores well on our pedagogical rubric.

我们的模型训练分为两个阶段:(1) 摹本和 (2) DPO。摹本是增强小型 LLM 能力的常用方法,通过模仿更大 LLM 的行为 [ 52]。在我们的案例中,我们在 GPT-4o 生成的候选导师话语上微调 Llama 3.1 8B。通过这个摹本阶段,我们获得了一个在我们的教学评估标准上得分良好的本地模型。

We then use DPO and our preference pairs to further steer the distilled model towards effective tutoring.

DPO trains an LLM by contrasting outputs in a preference pair given the same input prompt, using the following objective:

然后我们使用 DPO 和我们的偏好对来进一步引导摹本模型朝向有效的教学。DPO 通过在相同输入提示下对比偏好对中的输出来训练 LLM,使用以下目标:

where and represent the preferred and unpreferred tutor utterances, respectively. represents the input prompt, comprising an instruction, the context of the dialogue, and the dialogue history . denotes the model being trained, represents a frozen reference model, and is a hyperparameter that controls the divergence between the learned and reference policies.

其中 和 分别代表偏好和不受偏好的导师话语。 代表输入提示,包括指令、对话上下文和对话历史 。 表示正在训练的模型, 代表一个冻结的参考模型, 是一个控制学习策略和参考策略之间差异的超参数。

In this work, we use the distilled model as the reference model and for initializing the weights of . We find the distilled model works much better than using the base Llama model, since the distilled model already performs better on the rubric. Additionally, we set , a relatively low value for DPO compared to a common value of . The low value allows to diverge more from , which we find necessary to increase LLMKT’s predictions of eliciting correct student responses in the next dialogue turn.

在这项工作中,我们使用蒸馏模型作为参考模型 ,并使用它来初始化权重 。我们发现蒸馏模型比使用基础 Llama 模型效果要好得多,因为蒸馏模型在评分标准上已经表现更好。此外,我们设置了 ,这是一个相对于常见值 来说相对较低的低 DPO 值。低 值允许 更多地偏离 ,我们发现这对于增加 LLMKT 在下一轮对话中预测学生正确回答的准确性是必要的。

4 Experimental Settings 4 实验设置

4.1 Dataset 4.1 数据集

We evaluate our framework using the MathDial dataset [29], which consists of tutoring dialogues focused on mathematics problems from GSM8K [5]. Each dialogue is centered around an incorrect student solution to the math problem, and the goal of the dialogue is for the tutor to guide the student to the correct solution by addressing their misconceptions. Tutors are role-played by crowd workers, while students are simulated by GPT-3.5. Despite only being half-authentic, MathDial is the largest publicly available one-on-one tutor-student math dialogue dataset to the best of our knowledge. To estimate correctness with LLMKT, which requires knowledge component labels at the current turn, we use the annotated knowledge components from the Dialogue KT version of the dataset [38] and filter out unlabeled turns.

我们使用 MathDial 数据集[29]评估我们的框架,该数据集包含专注于数学问题的辅导对话,源自 GSM8K[5]。每个对话都围绕学生错误的数学问题解决方案展开,对话的目标是辅导员通过纠正学生的误解来引导学生找到正确答案。辅导员由众包工作者扮演,学生由 GPT-3.5 模拟。尽管只有半真实性,但据我们所知,MathDial 是目前最大公开的一对一辅导员-学生数学对话数据集。为了使用 LLMKT 估计当前回合的正确性(该评估需要当前回合的知识成分标签),我们使用数据集的 Dialogue KT 版本[38]中标注的知识成分,并过滤掉未标注的回合。

We follow the original MathDial train/test split. After filtering, our test set has 588 dialogues with 3,101 tutor turns. We split the train set into a 80/20 train/validation split at the dialogue-level, resulting in 1,809/453 dialogues with 11,058/2,811 tutor turns. When creating our overgenerated tutor turn dataset for distillation and DPO training, we take a subset of the train/validation split to reduce labeling costs, resulting in 483/135 dialogues with 3,080/920 GPT-4o-generated tutor utterances for distillation and 9,662/3,095 preference pairs, with our default parameters of and , for DPO.

我们遵循原始的 MathDial 训练/测试划分。经过筛选后,我们的测试集包含 588 个对话,共 3,101 个导师回合。我们将训练集在对话级别上按 80/20 的比例划分为训练集和验证集,结果得到 1,809/453 个对话,分别包含 11,058/2,811 个导师回合。在创建用于蒸馏和 DPO 训练的过度生成的导师回合数据集时,我们选取训练/验证划分的一个子集以降低标注成本,最终得到 483/135 个对话,其中包含 3,080/920 个用于蒸馏的 GPT-4o 生成的导师语句,以及 9,662/3,095 个偏好对,使用我们的默认参数 和 进行 DPO。

4.2 Baselines 4.2 基线

We compare our preference-optimized LLM, which we refer to as DPO, with Llama 3.1 8B as the base model, against the following baselines: the Base model of Llama 3.1 8B prompted with our evaluation criteria (rubric and intending to elicit correct student responses); its supervised fine-tuned version on human tutor utterances in the original dataset, SFT; a fine-tuned version distilled from GPT-4o-generated utterances detailed above in Section 3.4, Distill; GPT-4o, the large, proprietary LLM, which is prompted with our evaluation criteria; and finally, the Human Tutor utterances from the original MathDial dataset.

我们比较了我们的偏好优化 LLM,我们称之为 DPO,与 Llama 3.1 8B 作为基础模型,与以下基线进行对比:使用我们的评估标准(评分表和旨在引出正确学生回答)提示的 Llama 3.1 8B 基础模型;在原始数据集中人类导师话语上的监督微调版本,SFT;从第 3.4 节中详细说明的 GPT-4o 生成的话语蒸馏出的微调版本,Distill;GPT-4o,大型专有 LLM,使用我们的评估标准进行提示;最后,原始 MathDial 数据集中的人类导师话语。

4.3 Automated Metrics 4.3 自动指标

We evaluate tutor utterances on both student outcomes and pedagogical principles. Student outcome prediction uses LLMKT to estimate the probability of a correct student response, averaged across turns. Evaluating how well the utterance follows the pedagogical principles will be reported in the same order as in Table 1, reporting scores for Acc. (Accuracy), Prog. (Progress), Err. (Error Identification), Hint (Strategic Hinting), Wth. (Withholding), and Enc. (Encouraging), along with an Overall score.

我们评估导师话语对学生结果和教学原则的影响。学生结果预测使用 LLMKT 来估计正确学生回答的概率,并在回合间取平均值。评估话语遵循教学原则的程度将按照表 1 的顺序报告,报告 Acc.(准确率)、Prog.(进步)、Err.(错误识别)、Hint(策略性提示)、Wth.(保留)和 Enc.(鼓励)的分数,以及总体分数。

4.4 Model Parameters 4.4 模型参数

We use the meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct model from Hugging Face [11] for all local experiments. To adapt the model, we use Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [18] with a rank parameter of , scaling factor , and a dropout rate of 0.05. We train using the AdamW optimizer, with a learning rate of for distillation and for DPO, with a linear warmup phase for the first of training steps. We use an effective batch size of with gradient accumulation, set weight decay to , and set a gradient clipping maximum norm of . We evaluate the loss on the validation set after each epoch, and achieve the minimum validation loss after three epochs for distillation and after one epoch for DPO. At test time, we generate tutor utterances using greedy decoding. We conduct all experiments on NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPUs.

我们使用 Hugging Face 的 meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct 模型 [ 11] 进行所有本地实验。为了适配模型,我们使用低秩适配(LoRA)[ 18],设置秩参数为 ,缩放因子为 ,以及 dropout 率为 0.05。我们使用 AdamW 优化器进行训练,蒸馏阶段的学习率为 ,DPO 阶段的学习率为 ,并在训练的前 个步骤中进行线性预热。我们使用 的有效批大小,并采用梯度累积,将权重衰减设置为 ,梯度裁剪的最大范数为 。每轮训练后,我们在验证集上评估损失,蒸馏阶段在三轮训练后达到最小验证损失,DPO 阶段在第一轮训练后达到最小验证损失。测试时,我们使用贪婪解码生成助教话语。所有实验均在 NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU 上进行。

5 Experimental Results 5 实验结果

5.1 Quantitative Results 5.1 定量结果

表 2:测试集上每种方法的助教话语评估结果。每个指标的最佳结果加粗显示,次优结果加下划线。DPO 在提高学生正确预测方面显著优于所有方法,并且在教学评估方面的表现与 GPT-4o 非常接近。

| Student Outcomes 学生成果 | Pedagogical Principles 教学原则 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method 方法 | Acc. 准确率 | Prog. 进步 | Err. 错误。 | Hint 提示 | Wth. 什么。 | Enc. 编码。 | Overall 总体 | |

| Human Tutor 人类导师 | 0.45 | 0.99 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.97 | 0.53 | 6.97 |

| GPT-4o - Proprietary LLM GPT-4o - 专有 LLM | ||||||||

| Base Model 基础模型 | 0.49 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 9.40 |

| Llama 3.1 8B Instruct - Open-source LLM Llama 3.1 8B Instruct - 开源 LLM |

||||||||

| Base Model 基础模型 | 0.43 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.94 | 0.62 | 7.20 |

| SFT | 0.47 | 0.86 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.90 | 0.31 | 4.73 |

| Distill 蒸馏 | 0.47 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.82 | 8.93 |

| DPO () DPO ( ) | 0.65 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 9.37 |

Table 2 shows the results of tutor utterance generation on the MathDial test set, across all methods on the automated metrics. We observe that DPO significantly outperforms all other methods on student correctness prediction, improving over the next best method, GPT-4o, by . This result shows that DPO training is necessary to generate tutor utterances that are more likely to achieve correct student responses, which cannot be achieved simply through prompting. Additionally, DPO achieves similar scores to GPT-4o on the pedagogical rubric, with both methods scoring very high on all rubric items and the overall score. This result shows that our DPO training pipeline can effectively bring the pedagogical ability of small, open-source LLMs with only 8B parameters to the level of very large, proprietary LLMs.

Moreover, we see that DPO improves over distillation on almost all metrics, showing that DPO is necessary to achieve both objectives.

表 2 展示了在 MathDial 测试集上,所有方法在自动指标方面的导师话语生成结果。我们观察到 DPO 在学生正确性预测方面显著优于所有其他方法,比下一最佳方法 GPT-4o 提高了 。这一结果表明,DPO 训练对于生成更有可能获得学生正确回答的导师话语是必要的,而这不是单纯通过提示就能实现的。此外,DPO 在教学法评分标准上的得分与 GPT-4o 相似,两种方法在所有评分标准项目及总分上均得分非常高。这一结果表明,我们的 DPO 训练流程能够有效将仅含 8B 参数的小型开源 LLM 的教学能力提升至大型专有 LLM 的水平。此外,我们看到 DPO 在几乎所有指标上都优于蒸馏,这表明 DPO 对于实现两个目标都是必要的。

A notable observation is that human-written tutor utterances, while almost always accurate, score relatively low on most other rubric items. This result is not surprising since human tutors do not act according to our evaluation rubric; many of the human utterances are relatively short and simply ask the student to retry without giving guidance, and occasionally feature the tutor getting frustrated with the student. As a result, the SFT model, trained on human tutor utterances, does not score high on our rubric; the distilled model and even the base Llama model significantly outperform it on the rubric items.

一个显著的观察是,人类编写的导师话语虽然几乎总是准确的,但在大多数其他评估标准项上的得分相对较低。这个结果并不令人意外,因为人类导师并不按照我们的评估标准行事;许多人类话语相对简短,仅仅要求学生重试而不提供指导,并且偶尔会表现出导师对学生感到沮丧。因此,在人类导师话语上训练的 SFT 模型在我们的评估标准上得分不高;蒸馏模型甚至基础 Llama 模型在评估标准项上显著优于它。

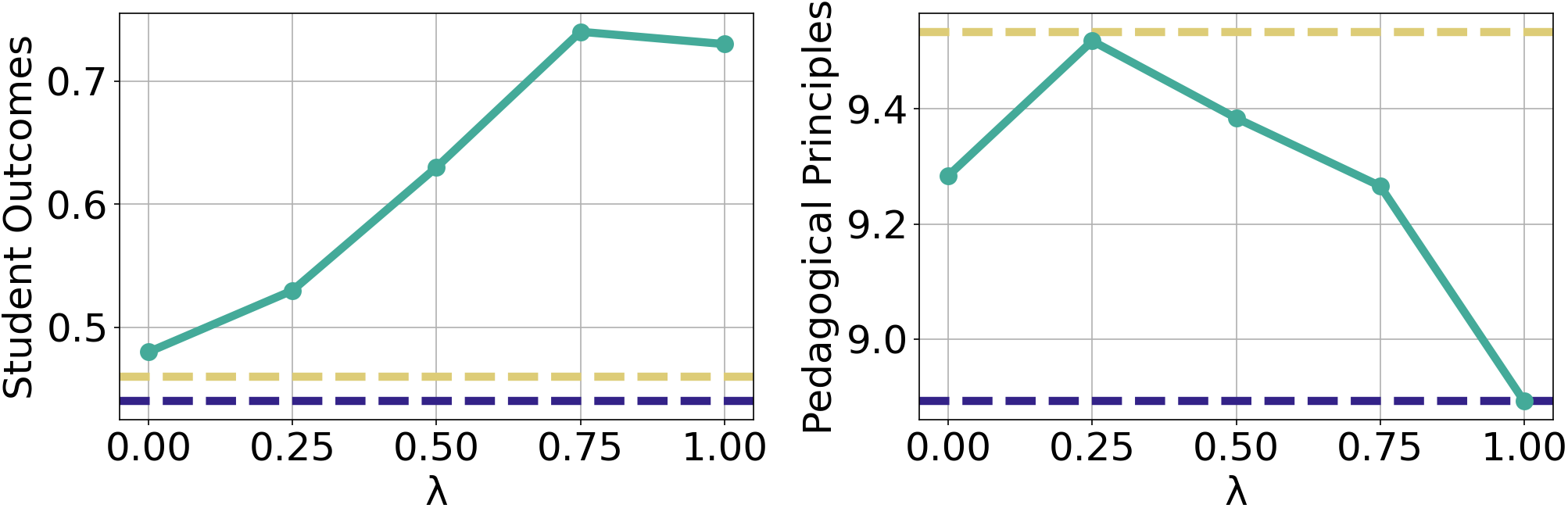

图 2:我们调整 DPO 训练中 值的实验结果。左:学生正确性预测随 变化。右:教学评估标准得分随 变化。我们还展示了 GPT-4o 和蒸馏模型的值以供比较。

Student Outcomes vs. Pedagogical Principles

We investigate how adjusting the value of can balance the two goals of maximizing student outcomes under LLMKT and following pedagogical principles. We vary the value of , where larger values attribute more weight to the student correctness prediction objective, and evaluate on a subset of the data with 500 turn pairs. Figure 2 shows the result of this experiment. We see that, as expected, increasing from to generally increases student correctness prediction performance while generally decreasing the rubric score. Practitioners can get their desired balance by changing ; for example, a value of around to can maintain a relatively high score on the pedagogical rubric while significantly improving performance on soliciting correct responses from students. Perhaps surprisingly, changing from to does not increase student outcome performance, while decreasing from to decreases pedagogical performance. This result implies that a small reward signal from correctness prediction may implicitly help pedagogical effectiveness, and vice versa.

学生成果与教学原则 我们研究了如何调整 的值来平衡 LLMKT 下最大化学生成果和遵循教学原则的两个目标。我们改变 的值,其中较大的值将更多权重赋予学生正确性预测目标,并在包含 500 对回合的子集数据上进行评估。图 2 显示了该实验的结果。我们看到,正如预期的那样,将 从 增加到 通常会提高学生正确性预测性能,同时通常会降低评分标准分。从业者可以通过改变 来获得他们期望的平衡;例如, 到 的值可以在保持教学评分标准相对较高分数的同时显著提高从学生那里获取正确回答的性能。或许令人惊讶的是,将 从 改为 并没有提高学生成果性能,而将 从 减少到 则降低了教学性能。这一结果表明,来自正确性预测的小奖励信号可能隐含地有助于教学效果,反之亦然。

5.2 Qualitative Analysis 5.2 定性分析

We conduct a qualitative analysis of generated tutor utterances to investigate the strengths and weaknesses of our method, how it compares to baselines, and what types of patterns emerge in the model-generated text.

我们对生成的导师话语进行定性分析,以研究我们方法的优缺点、它如何与基线比较,以及模型生成文本中出现的模式类型。

Table 3 shows an example dialogue context and tutor utterances from the human tutor, GPT-4o, and DPO.

We see that the human tutor states that the student is not correct and prompts the student to try again, providing a subtle hint to focus on the cost of the dozen. However, this utterance neither gives LLMKT, the student model, any confidence in the student being able to answer correctly, nor follows strong pedagogical principles. GPT-4o guides the student toward correctly calculating the profit, but directly provides half of the solution in its hint, limiting deep student engagement. It also poses the challenging task of computing the total profit, which requires multiple calculation steps. Since the student is still struggling with unit conversion, LLMKT is not confident that the student will respond correctly. In contrast, our DPO-trained model provides an actionable hint for the student, following the rubric. It also poses the simpler task of asking the student to first find the cost of a half dozen, which is necessary for later steps. As a result, LLMKT is confident the student can respond correctly.

表 3 展示了人类导师、GPT-4o 和 DPO 提供的对话上下文和导师话语示例。我们看到人类导师指出学生回答不正确,并提示学生再试一次,同时巧妙地暗示学生应关注一打的成本。然而,这句话既没有给 LLMKT(学生模型)任何学生能够正确回答的信心,也没有遵循强烈的教学习惯。GPT-4o 引导学生正确计算利润,但在提示中直接提供了半个解决方案,限制了学生的深度参与。它还提出了一个计算总利润的挑战性任务,需要多个计算步骤。由于学生仍在挣扎于单位转换,LLMKT 并不确定学生能正确回答。相比之下,我们训练的 DPO 模型为学生提供了可操作的提示,并遵循评分标准。它还提出了一个更简单的任务,要求学生首先找出半打的成本,这是后续步骤所必需的。因此,LLMKT 确信学生能够正确回答。

Overall, we find that our DPO-trained model excels at posing concrete tasks that are nontrivial, but more feasible for students compared to GPT-4o. We observe that the behavior of posing tasks this way is the primary way of achieving higher predictions for student correctness, and appears to be an emergent behavior of training on the LLMKT-derived scores. While the tasks sometimes only ask the student to perform simple arithmetic, they are typically more involved. For example, in another dialogue, the model asks “How long does it take to download 200 GB at a rate of 2 GB/minute?” This task requires the student to set up a single variable equation and understand the roles of the given values. We also find that the DPO-trained model is more likely to ask questions, whereas other methods often directly tell the student to perform a task.

总的来说,我们发现经过 DPO 训练的模型在提出具体任务方面表现出色,这些任务比 GPT-4o 提出的任务更非平凡,但对学生来说更可行。我们观察到,以这种方式提出任务的行为是提高学生正确率预测的主要方式,并且似乎是训练在 LLMKT 衍生分数上的涌现行为。虽然这些任务有时只要求学生进行简单的算术运算,但通常更复杂。例如,在另一个对话中,模型会问“下载 200GB 数据以每分钟 2GB 的速度需要多长时间?”这个任务要求学生建立单一变量方程并理解给定值的角色。我们还发现,DPO 训练的模型更倾向于提问,而其他方法通常直接告诉学生执行任务。

However, both LLMs still have some limitations, particularly when students give partially correct responses. In these cases, the models may ignore the progress the student has made and focus on errors that are irrelevant to the recent student response. Correctly identifying errors in math with LLMs has been shown to be challenging in prior work as well [12, 27], indicating additional techniques may be needed to fix this behavior.

然而,LLMs 仍然存在一些局限性,尤其是在学生给出部分正确回答的情况下。在这些情况下,模型可能会忽略学生已经取得的进步,而专注于与最近学生回答无关的错误。先前的研究表明,使用 LLMs 正确识别数学错误也是一项挑战[12, 27],这表明可能需要额外的技术来纠正这种行为。

表 3:比较人类导师、GPT-4o 和 DPO 导师的语句,在学生结果(SO)和教学原则(PP)上的表现。Brown 突出了导师提出任务。为了简洁,对话上下文中的一些无关文本已被删除。

| Problem 问题 | |||

|

Chloe bought chocolate-dipped strawberries at $50 a dozen. She then sold them for $30 for half a dozen. How much is Chloe’s profit if she sold 50 dozens? Chloe 买了每打 50 美元的巧克力蘸草莓。然后她以每半打 30 美元的价格出售。如果 Chloe 出售了 50 打,她的利润是多少? |

|||

| Dialogue History 对话历史 | |||

|

Hey Alejandra. If Chloe buys the strawberries at $50 for 12 and sells them for $30 for 6, how much profit would that be for one dozen? 嘿阿莱杭德拉。如果克洛伊以每打 50 美元的价格购买草莓,并以每 6 个 30 美元的价格出售,那么每打能赚多少利润? |

|||

|

For one dozen, Chloe would make a profit of $20, which is $50 - $30 = $20. 每打克洛伊能赚 20 美元,即 50 美元减去 30 美元等于 20 美元。 |

|||

|

Remember that she’s selling half a dozen for $30. How many half dozen can she sell from each $50 dozen she buys? 记住她以 30 美元的价格出售半打。她从每打 50 美元的购买中能卖多少半打? |

|||

|

She can sell two half dozen for each $50 dozen she buys, so she can make a profit of $60 from each $50 dozen. 她可以卖出每 50 打她购买的 2 个半打,因此她可以从每 50 打中赚取 60 美元的利润。 |

|||

| Next Tutor Turn () Candidates 下一个导师回合( )候选人 |

|||

| Method 方法 | Tutor Utterance 导师话语 | SO | PP |

| Human Tutor 人类导师 |

Remember it’s not $60 profit, because they cost her to buy them. Try again. 记住,不是$60 的利润,因为购买它们要花她的钱。再试一次。 |

0.33 | 4 |

| GPT-4o |

It looks like there’s a misunderstanding in your calculations. Remember, Chloe’s cost for half a dozen is $25 (since $50 per dozen divided by 2). She sells half a dozen for $30, so her profit per half dozen is $30 - $25 = $5. Try recalculating her total profit using this correct profit per half dozen. 看起来你的计算有误。记住,Chloe 买半打要花$25(因为每打$50 除以 2)。她卖半打$30,所以她每半打的利润是$30 - $25 = $5。用这个正确的每半打利润重新计算她的总利润。 |

0.59 | 10 |

| DPO |

It looks like there’s a misunderstanding. If Chloe buys a dozen for $50 and sells half a dozen for $30, let’s first find out how much she paid for half a dozen. If $50 is for 12, how much is $50 divided by 2? 看起来你理解有误。如果 Chloe 买一打$50,卖半打$30,让我们先算出她买半打花了多少钱。如果$50 是 12 个,那么$50 除以 2 是多少? |

0.84 | 10 |

5.3 Human Evaluation 5.3 人工评估

We also conduct a human evaluation to further assess different tutor models and how our automated metrics align with human judgment.

我们也进行人工评估,以进一步评估不同的导师模型,以及我们的自动化指标与人类判断的一致性。

We recruit two independent volunteer university students to annotate tutor utterances according to our evaluation metrics.

We randomly sample 10 dialogues from the test set after filtering based on toxicity and low quality ground-truth tutor utterances.

The annotators evaluate 5 consecutive tutor turns from each dialogue, resulting in a total of 50 evaluation instances. At each instance, we show participants the dialogue so far and next tutor utterance candidates generated by (1) human tutors, (2) GPT-4o, and (3) our DPO-trained model, in random order without revealing the method.

我们招募了两位独立的大学生志愿者,根据我们的评估指标对导师的发言进行标注。在过滤掉有毒性和低质量的真实导师发言后,我们从测试集中随机抽取了 10 个对话。标注者评估每个对话中连续的 5 个导师发言,总共产生 50 个评估实例。在每个实例中,我们向参与者展示到目前为止的对话以及由(1)人类导师、(2)GPT-4o 和(3)我们训练的 DPO 模型生成的下一个导师发言候选,以随机顺序显示,不透露方法。

For student outcome prediction, annotators rank the three candidate utterances based on how likely they think each one will lead to a correct student response. We ask annotators to take into account both the task posed in the turn and the student’s knowledge demonstrated in prior turns. We use rankings instead of absolute values since the latter may be harder for humans to calibrate.

For pedagogical principles, we simply ask annotators to follow the same evaluation rubric outlined in Table 1 and provide an overall score on a 1-10 scale.

对于学生表现预测,标注者根据他们认为每个候选话语可能引出正确学生回答的可能性对三个候选话语进行排序。我们要求标注者同时考虑该回合中提出的问题以及学生在先前回合中展现的知识。我们使用排序而不是绝对值,因为后者可能更难让人校准。对于教学原则,我们仅要求标注者遵循表 1 中概述的相同评估标准,并在 1-10 的量表上给出总体评分。

表 4:人工评估显示 DPO 的表现优于人类导师和 GPT-4o。

| Method 方法 | Correctness Rank↓ 正确性排名 ↓ | Rubric Score↑ 评分标准 ↑ |

|---|---|---|

| Human Tutor 人类导师 | 2.12 | 7.36 |

| GPT-4o | 2.13 | 8.07 |

| DPO | 1.75 | 8.55 |

Results Table 4 shows average student correctness ranks (rank means top-ranked) and rubric scores from human annotators. We see that DPO outperforms both human tutors and GPT-4o on both metrics, with all differences statistically significant () according to a paired t-test. Higher correctness ranks show that DPO learns how to pose tasks that are manageable to students, while the higher rubric score shows that it does so while maintaining pedagogical principles. Additionally, the higher rubric score may imply that the correctness objective also indirectly improves pedagogical quality.

While DPO outperforming GPT-4o on the rubric is contrary to the automated results in Table 2, the automated results may reflect self-bias from GPT-4o as the evaluator [50].

结果表 4 显示了学生正确性排名(排名 表示排名第一)和人类标注者的评分标准分数。我们看到 DPO 在两个指标上均优于人类导师和 GPT-4o,且所有差异根据配对 t 检验具有统计学意义( )。更高的正确性排名表明 DPO 学会了如何提出对学生来说可管理的任务,而更高的评分标准分数表明它在这样做时仍坚持教学原则。此外,更高的评分标准分数也可能意味着正确性目标也间接提高了教学质量。虽然 DPO 在评分标准上优于 GPT-4o 与表 2 中的自动化结果相反,但自动化结果可能反映了作为评估者的 GPT-4o 的自我偏见[50]。

Since these evaluation tasks can be highly subjective, we also investigate the inter-rater agreement between the two human annotators and the automated metrics. We use Kendall’s [21] for correctness ranks and Pearson’s correlation coefficient [25] for rubric scores. For correctness ranks, Kendall’s is only between the two annotators and averages between LLMKT and both annotators. This low agreement is not surprising due to the subjective nature of the task; we find that there are many near-ties between different candidate utterances according to LLMKT’s output probabilities. For rubric scores, the inter-rater agreement is notably higher: Pearson’s is between the two annotators and averages between GPT-4o and both annotators, the latter being statistically significant. This result suggests that evaluating pedagogical principles is much easier than predicting student correctness, though the former is still subjective, since annotators may value certain rubric items differently.

由于这些评估任务可能具有高度主观性,我们还研究了两位人类标注者和自动指标之间的评分者间一致性。我们使用肯德尔τ系数 [ 21]评估正确性排序,使用皮尔逊相关系数 [ 25]评估评分标准得分。对于正确性排序,肯德尔τ系数 在两位标注者之间的相关性仅为 ,而与 LLMKT 的平均相关性为 。由于任务的主观性,这种低一致性并不令人意外;我们发现根据 LLMKT 的输出概率,不同候选话语之间存在许多接近平局的情况。对于评分标准得分,评分者间一致性明显更高:皮尔逊相关系数 在两位标注者之间的相关性为 ,而与 GPT-4o 的平均相关性为 ,后者具有统计学意义。这一结果表明,评估教学原则比预测学生正确性要容易得多,尽管前者仍然是主观的,因为标注者可能对不同的评分标准项有不同的评价。

Overall, despite showing some promise through preliminary evaluation, it is important to deploy our trained tutor LLMs to real students and test whether they actually lead to good student learning outcomes.

总体而言,尽管初步评估显示出一些潜力,但将我们训练的导师 LLMs 部署给真实学生,并测试它们是否确实能带来良好的学生学习成果,这一点非常重要。

6 Conclusions and Future Work

6 结论与未来工作

In this paper, we introduced a methodology to train LLM tutors to maximize student outcomes in dialogues while maintaining high pedagogical quality. We use student simulation to predict how likely a tutor utterance will yield a correct student response, and use GPT-4o to evaluate the pedagogical quality of tutor utterances using a rubric. We use both sets of predictions to score overgenerated tutor utterances and fine-tune Llama 3.1 8B with direct preference optimization. Our resulting model significantly outperforms other methods for increasing predicted student outcomes, and matches the performance of GPT-4o, a much larger closed model, on pedagogical aspects. There are many avenues for future work. First, an evaluation with real students should be carried out to determine if our methods are still effective in real-world scenarios. Second, future work should investigate how to optimize for longer-term learning outcomes, such as concept mastery or performance on post-dialogue assessments. Third, future work should include estimates of student affect and engagement as part of the reward. Finally, future work should apply our method to dialogues in non-math domains, such as language learning or computer science.重试 错误原因

Acknowledgments 致谢

We thank Adriana Caraeni and Henry Yang for helpful discussions around this work. This work is partially supported by Renaissance Philanthropy via the learning engineering virtual institute (LEVI) and NSF grants 2118706, 2237676, and 2341948.重试 错误原因

References

- [1] John R Anderson, Albert T Corbett, Kenneth R Koedinger, and Ray Pelletier. Cognitive tutors: Lessons learned. The journal of the learning sciences, 4(2):167–207, 1995.

- [2] Nischal Ashok Kumar and Andrew Lan. Improving socratic question generation using data augmentation and preference optimization. In Proceedings of the 19th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2024), pages 108–118, Mexico City, Mexico, June 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- [3] Dejun Cai, Yuan Zhang, and Bintao Dai. Learning path recommendation based on knowledge tracing model and reinforcement learning. In 2019 IEEE 5th international conference on computer and communications (ICCC), pages 1881–1885. IEEE, 2019.

- [4] Carnegie Learning. Livehint overview. Online: https://support.carnegielearning.com/help-center/math/livehint/article/livehint-overview/, 2024.

- [5] Karl Cobbe, Vineet Kosaraju, Mohammad Bavarian, Mark Chen, Heewoo Jun, Lukasz Kaiser, Matthias Plappert, Jerry Tworek, Jacob Hilton, Reiichiro Nakano, Christopher Hesse, and John Schulman. Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.14168, 2021.

- [6] Common Core State Standards Initiative. Mathematics standards. Online: https://www.thecorestandards.org/Math/, 2024.

- [7] Albert Corbett and John Anderson. Knowledge tracing: Modeling the acquisition of procedural knowledge. User Model. User-adapted Interact., 4(4):253–278, Dec. 1994.

- [8] Peng Cui and Mrinmaya Sachan. Adaptive and personalized exercise generation for online language learning. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 10184–10198, 2023.

- [9] Dorottya Demszky, Jing Liu, Zid Mancenido, Julie Cohen, Heather Hill, Dan Jurafsky, and Tatsunori B Hashimoto. Measuring conversational uptake: A case study on student-teacher interactions. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 1638–1653, 2021.

- [10] Abhimanyu Dubey, Abhinav Jauhri, Abhinav Pandey, Abhishek Kadian, Ahmad Al-Dahle, Aiesha Letman, Akhil Mathur, Alan Schelten, Amy Yang, Angela Fan, et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783, 2024.

- [11] Hugging Face. Hugging face - the ai community building the future. https://huggingface.co/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-02-18.

- [12] Nigel Fernandez, Alexander Scarlatos, Wanyong Feng, Simon Woodhead, and Andrew Lan. DiVERT: Distractor generation with variational errors represented as text for math multiple-choice questions. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 9063–9081, Miami, Florida, USA, November 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- [13] Aritra Ghosh, Neil Heffernan, and Andrew S Lan. Context-aware attentive knowledge tracing. In Proc. ACM SIGKDD, pages 2330–2339, 2020.

- [14] Arthur C Graesser, Kurt VanLehn, Carolyn P Rosé, Pamela W Jordan, and Derek Harter. Intelligent tutoring systems with conversational dialogue. AI magazine, 22(4):39–39, 2001.

- [15] Jieun Han, Haneul Yoo, Junho Myung, Minsun Kim, Hyunseung Lim, Yoonsu Kim, Tak Yeon Lee, Hwajung Hong, Juho Kim, So-Yeon Ahn, et al. Llm-as-a-tutor in efl writing education: Focusing on evaluation of student-llm interaction. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Customizable NLP: Progress and Challenges in Customizing NLP for a Domain, Application, Group, or Individual (CustomNLP4U), pages 284–293, 2024.

- [16] Joy He-Yueya, Noah D. Goodman, and Emma Brunskill. Evaluating and optimizing educational content with large language model judgments. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, page 68–82, 2024.

- [17] Joy He-Yueya and Adish Singla. Quizzing policy using reinforcement learning for inferring the student knowledge state. International Educational Data Mining Society, 2021.

- [18] Edward J Hu, Yelong Shen, Phillip Wallis, Zeyuan Allen-Zhu, Yuanzhi Li, Shean Wang, Lu Wang, and Weizhu Chen. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09685, 2021.

- [19] Qinjin Jia, Mitchell Young, Yunkai Xiao, Jialin Cui, Chengyuan Liu, Parvez Rashid, and Edward Gehringer. Insta-reviewer: A data-driven approach for generating instant feedback on students’ project reports. International Educational Data Mining Society, 2022.

- [20] Sanjit Kakarla, Danielle Thomas, Jionghao Lin, Shivang Gupta, and Ken Koedinger. Using large language models to assess tutors’ performance in reacting to students making math errors. In AI for Education: Bridging Innovation and Responsibility at the 38th AAAI Annual Conference on AI, 2024.

- [21] Maurice George Kendall. Rank correlation methods. 1948.

- [22] Khan Academy. Supercharge your teaching experience with khanmigo. Online: https://www.khanmigo.ai/, 2023.

- [23] Kyuyoung Kim, Ah Jeong Seo, Hao Liu, Jinwoo Shin, and Kimin Lee. Margin matching preference optimization: Enhanced model alignment with granular feedback. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, pages 13554–13570, Miami, Florida, USA, November 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- [24] Lars Krupp, Steffen Steinert, Maximilian Kiefer-Emmanouilidis, Karina E Avila, Paul Lukowicz, Jochen Kuhn, Stefan Küchemann, and Jakob Karolus. Challenges and opportunities of moderating usage of large language models in education. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, pages 249–254, 2024.

- [25] Joseph Lee Rodgers and W Alan Nicewander. Thirteen ways to look at the correlation coefficient. The American Statistician, 42(1):59–66, 1988.

- [26] Anna Lieb and Toshali Goel. Student interaction with newtbot: An llm-as-tutor chatbot for secondary physics education. In Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages 1–8, 2024.

- [27] Naiming Liu, Shashank Sonkar, Zichao Wang, Simon Woodhead, and Richard G Baraniuk. Novice learner and expert tutor: Evaluating math reasoning abilities of large language models with misconceptions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.02439, 2023.

- [28] Naiming Liu, Zichao Wang, Richard Baraniuk, and Andrew Lan. Open-ended knowledge tracing for computer science education. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022.

- [29] Jakub Macina, Nico Daheim, Sankalan Chowdhury, Tanmay Sinha, Manu Kapur, Iryna Gurevych, and Mrinmaya Sachan. MathDial: A dialogue tutoring dataset with rich pedagogical properties grounded in math reasoning problems. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, pages 5602–5621, Singapore, December 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- [30] Andre Nickow, Philip Oreopoulos, and Vincent Quan. The impressive effects of tutoring on prek-12 learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Working Paper 27476, National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2020.

- [31] Benjamin D Nye, Dillon Mee, and Mark G Core. Generative large language models for dialog-based tutoring: An early consideration of opportunities and concerns. In LLM@ AIED, pages 78–88, 2023.

- [32] OpenAI. Hello gpt-4o, May 2024. Accessed: 2025-02-19.

- [33] Sankalan Pal Chowdhury, Vilém Zouhar, and Mrinmaya Sachan. Autotutor meets large language models: A language model tutor with rich pedagogy and guardrails. In Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale, pages 5–15, 2024.

- [34] Minju Park, Sojung Kim, Seunghyun Lee, Soonwoo Kwon, and Kyuseok Kim. Empowering personalized learning through a conversation-based tutoring system with student modeling. In Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages 1–10, 2024.

- [35] Chris Piech, Jonathan Bassen, Jonathan Huang, Surya Ganguli, Mehran Sahami, Leonidas J Guibas, and Jascha Sohl-Dickstein. Deep knowledge tracing. In Proc. NeurIPS, pages 505–513, 2015.

- [36] Rafael Rafailov, Archit Sharma, Eric Mitchell, Christopher D Manning, Stefano Ermon, and Chelsea Finn. Direct preference optimization: Your language model is secretly a reward model. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 2024.

- [37] Anna N Rafferty, Emma Brunskill, Thomas L Griffiths, and Patrick Shafto. Faster teaching via pomdp planning. Cognitive science, 40(6):1290–1332, 2016.

- [38] Alexander Scarlatos, Ryan S. Baker, and Andrew Lan. Exploring knowledge tracing in tutor-student dialogues using llms. In Proceedings of the 15th Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference, LAK 2025, Dublin, Ireland, March 3-7, 2025. ACM, 2025.

- [39] Alexander Scarlatos, Digory Smith, Simon Woodhead, and Andrew Lan. Improving the validity of automatically generated feedback via reinforcement learning. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, pages 280–294. Springer, 2024.

- [40] Robin Schmucker, Meng Xia, Amos Azaria, and Tom Mitchell. Ruffle&riley: Insights from designing and evaluating a large language model-based conversational tutoring system. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, pages 75–90. Springer, 2024.

- [41] Shashank Sonkar, Naiming Liu, Debshila Mallick, and Richard Baraniuk. CLASS: A design framework for building intelligent tutoring systems based on learning science principles. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, pages 1941–1961, Singapore, December 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- [42] Shashank Sonkar, Kangqi Ni, Sapana Chaudhary, and Richard Baraniuk. Pedagogical alignment of large language models. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, pages 13641–13650, Miami, Florida, USA, November 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- [43] John Stamper, Ruiwei Xiao, and Xinying Hou. Enhancing llm-based feedback: Insights from intelligent tutoring systems and the learning sciences. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, pages 32–43. Springer, 2024.

- [44] Jacob Steiss, Tamara Tate, Steve Graham, Jazmin Cruz, Michael Hebert, Jiali Wang, Youngsun Moon, Waverly Tseng, Mark Warschauer, and Carol Booth Olson. Comparing the quality of human and chatgpt feedback of students’ writing. Learning and Instruction, 91:101894, 2024.

- [45] LearnLM Team. Learnlm: Improving gemini for learning, 2024.

- [46] Kurt VanLehn, Pamela W Jordan, Carolyn P Rosé, Dumisizwe Bhembe, Michael Böttner, Andy Gaydos, Maxim Makatchev, Umarani Pappuswamy, Michael Ringenberg, Antonio Roque, et al. The architecture of why2-atlas: A coach for qualitative physics essay writing. In Intelligent Tutoring Systems: 6th International Conference, ITS 2002 Biarritz, France and San Sebastian, Spain, June 2–7, 2002 Proceedings 6, pages 158–167. Springer, 2002.

- [47] Rose Wang, Qingyang Zhang, Carly Robinson, Susanna Loeb, and Dorottya Demszky. Bridging the novice-expert gap via models of decision-making: A case study on remediating math mistakes. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 2174–2199, 2024.

- [48] Rose E Wang, Ana T Ribeiro, Carly D Robinson, Susanna Loeb, and Dora Demszky. Tutor copilot: A human-ai approach for scaling real-time expertise. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.03017, 2024.

- [49] Canwen Xu, Corby Rosset, Ethan Chau, Luciano Corro, Shweti Mahajan, Julian McAuley, Jennifer Neville, Ahmed Awadallah, and Nikhil Rao. Automatic pair construction for contrastive post-training. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024, pages 149–162, Mexico City, Mexico, June 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- [50] Wenda Xu, Guanglei Zhu, Xuandong Zhao, Liangming Pan, Lei Li, and William Wang. Pride and prejudice: LLM amplifies self-bias in self-refinement. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 15474–15492, Bangkok, Thailand, August 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- [51] Boyang Yang, Haoye Tian, Weiguo Pian, Haoran Yu, Haitao Wang, Jacques Klein, Tegawendé F Bissyandé, and Shunfu Jin. Cref: An llm-based conversational software repair framework for programming tutors. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, pages 882–894, 2024.

- [52] Chuanpeng Yang, Yao Zhu, Wang Lu, Yidong Wang, Qian Chen, Chenlong Gao, Bingjie Yan, and Yiqiang Chen. Survey on knowledge distillation for large language models: Methods, evaluation, and application. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol., October 2024.

- [53] He Zhang, Jingyi Xie, Chuhao Wu, Jie Cai, ChanMin Kim, and John M Carroll. The future of learning: Large language models through the lens of students. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference on Information Technology Education, pages 12–18, 2024.