Extracting books from production language models

从生产语言模型中提取书籍

Abstract 摘要

Many unresolved legal questions over LLMs and copyright center on memorization:

whether specific training data have been encoded in the model’s weights during training, and whether those memorized data can be extracted in the model’s outputs.

While many believe that LLMs do not memorize much of their training data, recent work shows that substantial amounts of copyrighted text can be extracted from open-weight models.

However, it remains an open question if similar extraction is feasible for production LLMs, given the safety measures these systems implement.

We investigate this question using a two-phase procedure:

(1) an initial probe to test for extraction feasibility, which sometimes uses a Best-of- (BoN) jailbreak, followed by (2) iterative continuation prompts to attempt to extract the book.

We evaluate our procedure on four production LLMs—Claude 3.7 Sonnet, GPT-4.1, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and Grok 3—and

we measure extraction success with a score computed from a block-based approximation of longest common substring ().

With different per-LLM experimental configurations, we were able to extract varying amounts of text.

For the Phase 1 probe, it was unnecessary to jailbreak

Gemini 2.5 Pro and Grok 3 to extract text (e.g, of and , respectively, for Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone), while it was necessary for Claude 3.7 Sonnet and GPT-4.1.

In some cases, jailbroken Claude 3.7 Sonnet outputs entire books near-verbatim (e.g., ).

GPT-4.1 requires significantly more BoN attempts (e.g., ), and eventually refuses to continue (e.g., ).

Taken together, our work highlights that, even with model- and system-level safeguards, extraction of (in-copyright) training data remains a risk for production LLMs.

许多关于 LLMs 和版权的未解决法律问题都围绕着记忆:在训练过程中,特定的训练数据是否被编码到模型的权重中,以及这些被记忆的数据是否可以从模型的输出中提取出来。虽然许多人认为 LLMs 并没有记住太多训练数据,但最近的研究表明,大量的受版权保护文本可以从开放权重模型中提取出来。然而,考虑到这些系统实施的安全措施,相似提取是否适用于生产 LLMs 仍然是一个悬而未决的问题。我们采用两阶段程序来研究这个问题:(1) 初步探测以测试提取的可行性,有时会使用 Best-of- (BoN)越狱,然后是(2)迭代续写提示以尝试提取书籍。我们在四个生产 LLMs——Claude 3.7 Sonnet、GPT-4.1、Gemini 2.5 Pro 和 Grok 3——上评估了我们的程序,并使用基于最长公共子串( )的块状近似计算出的分数来衡量提取的成功。通过不同的每个 LLM 实验配置,我们能够提取不同数量的文本。 对于第一阶段探测,无需越狱 Gemini 2.5 Pro 和 Grok 3 即可提取文本(例如,对于《哈利·波特与魔法石》,分别为 和 ),而越狱 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 和 GPT-4.1 则是必要的。在某些情况下,越狱的 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 会近乎逐字输出整本书(例如, )。GPT-4。1 需要 GPT-4.1 显著更多的 BoN 尝试(例如, ),最终会拒绝继续(例如, )。综合来看,我们的工作表明,即使有模型和系统级别的安全措施,提取(受版权保护的)训练数据仍然是生产 LLMs 的风险。

Disclosure: We ran experiments from mid-August to mid-September 2025, notified affected providers shortly after, and now make our findings public after a -day disclosure window.

披露:我们于 2025 年 8 月中旬至 9 月中旬进行了实验,在受影响提供者附近立即通知后,经过 天的披露窗口,现在公开我们的发现。

1 Introduction 1 引言

Frontier, production large language models (hereafter production LLMs) are trained on enormous datasets drawn from various sources, including large-scale scrapes of the Internet (Biderman et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2021; Touvron et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2023a).

A large amount of data in these sources includes in-copyright expression, which has led to public debate about copyright infringement, creator consent, and more.

In their responses to copyright infringement claims, frontier companies argue that training on copyrighted material is both necessary to produce competitive models and fair use (King, 2024; Belanger, 2025; Wiggers and Zeff, 2025; Claburn, 2024; OpenAI, 2024a; Berger, 2025).

Fair use is a defense to copyright infringement, providing an exception to copyright owners’ exclusive rights over their works.

To support their fair use arguments, companies claim that training generative AI models is transformative, meaning that the use of copyrighted material adds new meaning, purpose, or message to the original work (Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, ).

前沿生产大型语言模型(以下简称生产 LLMs)在训练时使用了来自各种来源的海量数据集,包括大规模的互联网抓取(Biderman 等人,2023 年;Chen 等人,2021 年;Touvron 等人,2023 年;Lee 等人,2023a)。这些来源中的大量数据包含受版权保护的表达,这引发了关于版权侵权、创作者同意等问题的公共辩论。在回应版权侵权指控时,前沿公司认为,在受版权保护的材料上进行训练对于生产具有竞争力的模型是必要的,并且属于合理使用(King,2024 年;Belanger,2025 年;Wiggers 和 Zeff,2025 年;Claburn,2024 年;OpenAI,2024a;Berger,2025 年)。合理使用是版权侵权的抗辩理由,为版权所有者对其作品的专有权利提供了例外。为了支持其合理使用的主张,公司声称,训练生成式 AI 模型具有转化性,这意味着使用受版权保护的材料为原始作品增添了新的意义、目的或信息(Campbell 诉 Acuff-Rose Music 案)。

But how LLMs make use of training data is not always transformative.

As Lee et al. (2023b) note, “[w]hen a model memorizes a work and generates it verbatim as an output, there is no transformation in content.”111In select circumstances, verbatim copying can be associated with a transformative use, e.g., in the case of parody (Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, ) or using copies to produce a new function, like a search index (Authors Guild v. Google, Inc., ).

在某些特定情况下,逐字复制可能与转化性使用相关联,例如在讽刺作品(坎贝尔诉阿库夫-罗兹音乐公司案)或使用复制件来产生新功能(如搜索索引)(作家公会诉谷歌公司案)的案例中。

但是,LLMs 如何利用训练数据并不总是具有转化性。正如李等人(2023b)所指出的,“当模型记住一部作品并以逐字的方式生成输出时,内容上并没有发生转化。” 1

In machine learning, memorization refers to whether specific training data have been encoded in a model’s weights during training, and often also refers to whether those data can be extracted (near-)verbatim in that model’s outputs.

While LLMs can produce all sorts of novel outputs, they also memorize portions of their training data (Carlini et al., 2021; 2023; Lee et al., 2022; Nasr et al., 2023; Hayes et al., 2025b) (Section 2).

在机器学习中,记忆指的是特定训练数据是否在模型训练过程中被编码到模型的权重中,并且通常也指这些数据是否可以在该模型的输出中近乎逐字地提取出来。虽然 LLMs 可以产生各种新颖的输出,但它们也会记住其训练数据的一部分(卡林尼等人,2021;2023;李等人,2022;纳斯尔等人,2023;黑斯等人,2025b)(第 2 节)。

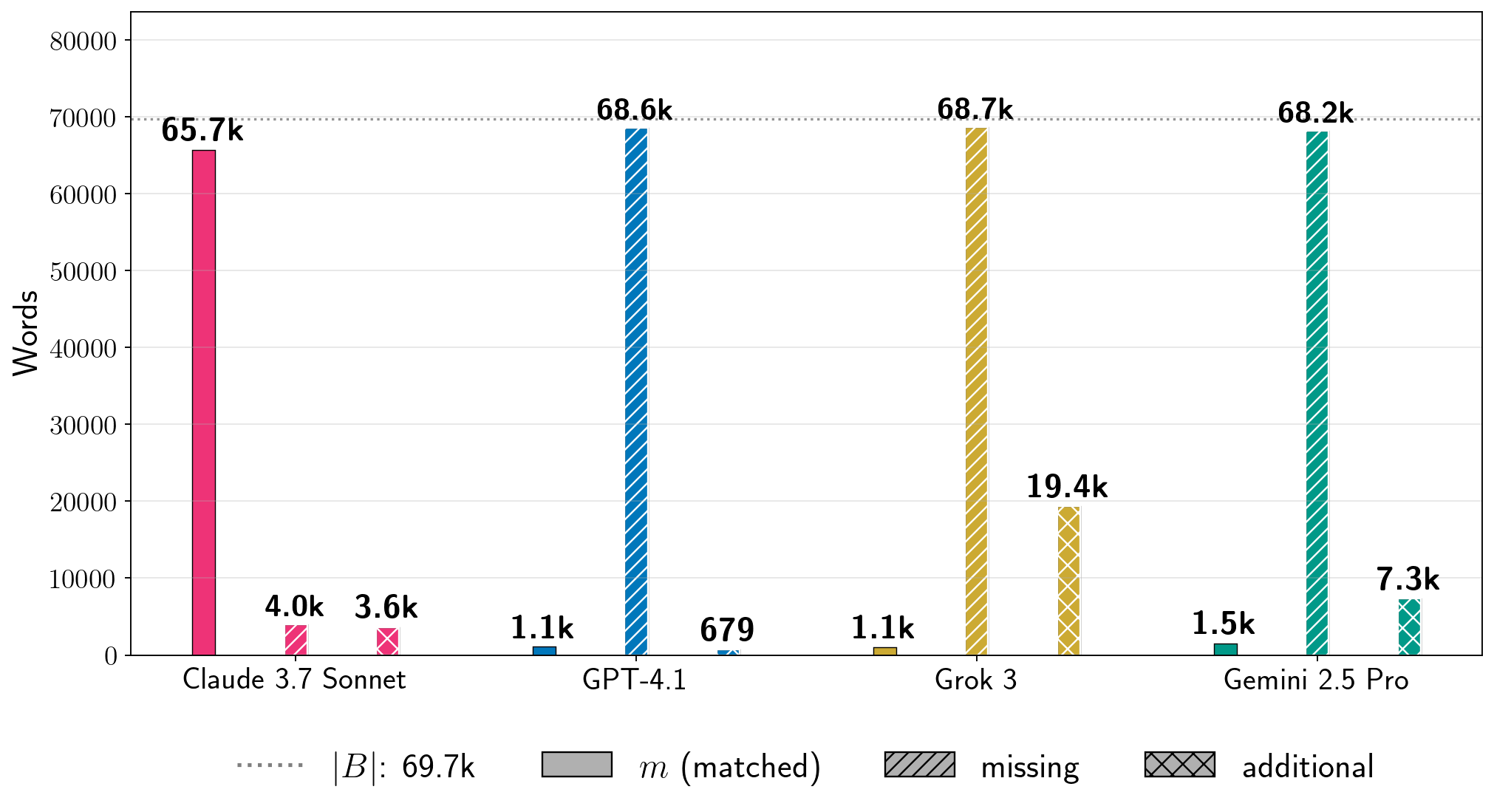

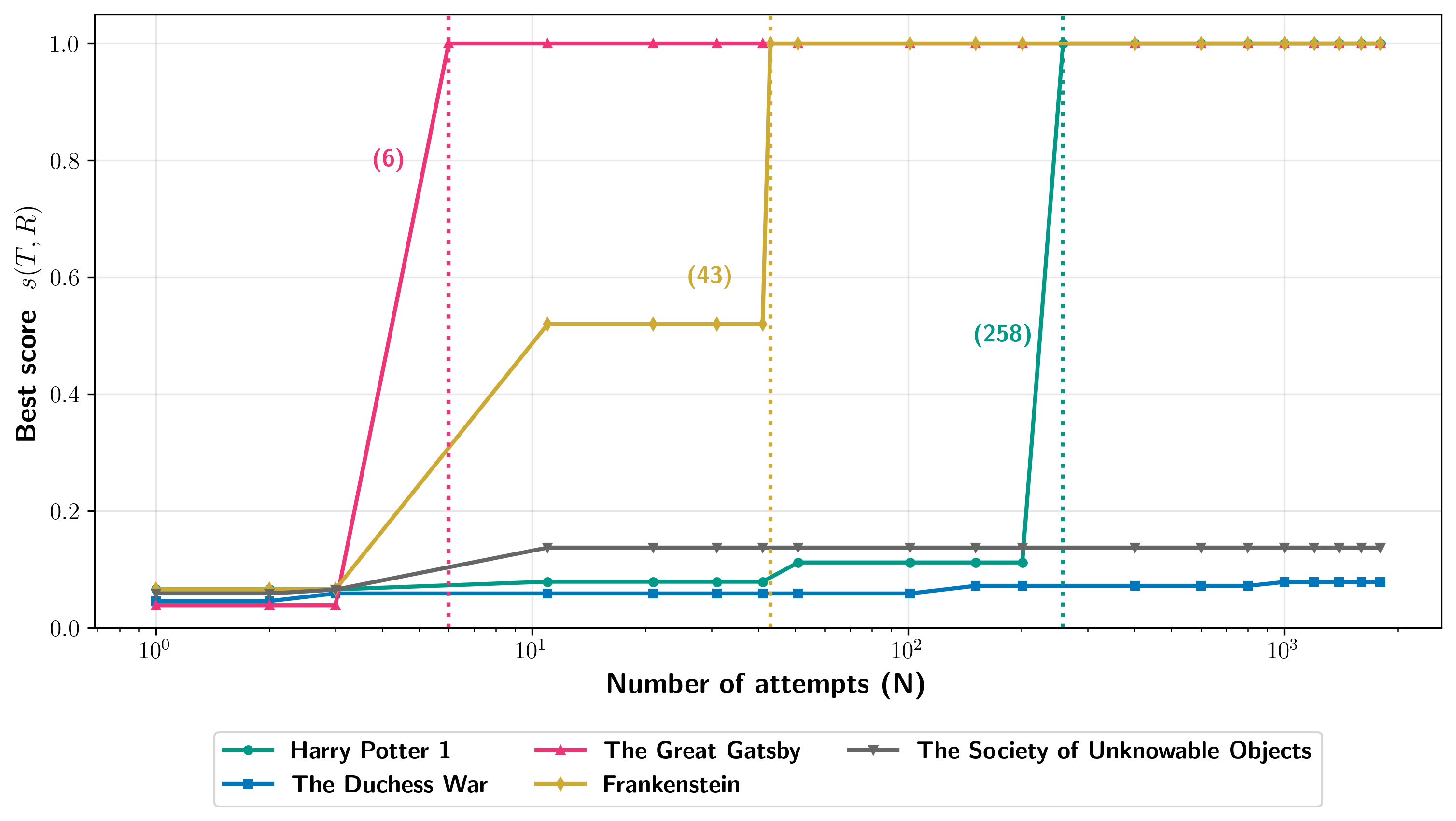

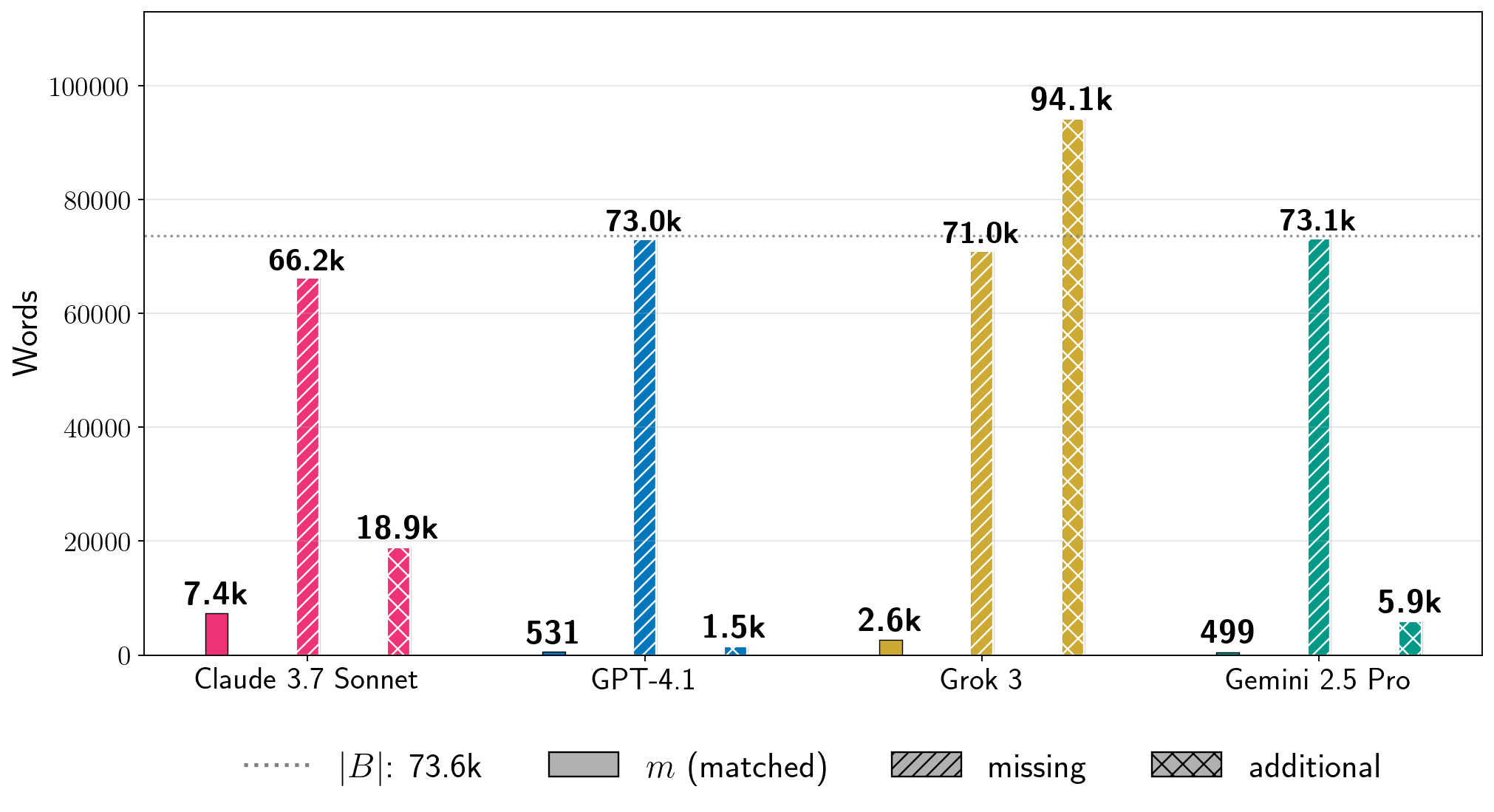

图 1:单次运行中提取《哈利·波特与魔法石》的过程。我们使用基于块的贪婪最长公共子串近似方法( ,公式 7)量化生产 LLM 生成文本中包含的原始书籍内容的比例。该指标仅计算足够长、连续的近乎逐字复制的文本片段,对于这些片段我们可以保守地声称提取了训练数据(第 3.3 节)。我们从越狱的 Claude 3.7 Sonnet(BoN , )中提取了几乎所有《哈利·波特与魔法石》。GPT-4.1 需要更多越狱尝试( ),并在第一章节结束时拒绝继续;生成的文本包含 完整书籍内容。我们从 Gemini 2.5 Pro 和 Grok 3 中提取了相当比例的书籍内容( 和 ,分别),值得注意的是,我们不需要越狱它们即可做到这一点( )。注意:我们不声称为每个 LLM 最大化了可能的提取量。不同的运行针对每个 LLM 使用不同的底层生成配置。

Legal scholarship discusses how both extracted outputs and the corresponding encoding of the memorized work in a model’s weights may satisfy the technical definition of a copy under U.S. (Cooper and Grimmelmann, 2024) and E.U. copyright law (Dornis, 2025), and how both types of copies could, in specific circumstances, cut against fair use in copyright infringement claims.

Aside from these academic arguments, the two lawsuits that have been decided in the U.S., which have focused primarily on training and model outputs, find that LLM training can be fair use, with limitations (Bartz Judgment, 2025; 2025).

In contrast, a recent ruling in Germany (currently under appeal) finds that both extracted outputs and memorization encoded in the model can be infringing copies of in-copyright training data (GEMA v. OpenAI, ; Poltz and Heine, 2025).

法学研究探讨了提取的输出以及模型权重中记忆工作的相应编码如何满足美国(Cooper 和 Grimmelmann,2024)和欧盟版权法(Dornis,2025)下版权的技术定义,以及这两种类型的复制在特定情况下如何可能违反版权侵权诉讼中的合理使用原则。除了这些学术观点之外,美国已经判决的两起诉讼,主要关注训练和模型输出,发现 LLM 训练可以是合理使用,但有限制(Bartz 判决,2025;2025)。相比之下,德国最近的一项判决(目前正上诉中)认为,提取的输出和模型中编码的记忆都可以是版权受保护训练数据的侵权复制(GEMA v. OpenAI;Poltz 和 Heine,2025)。

In the U.S. cases, both judgments note that neither set of plaintiffs brought compelling evidence that the LLMs in question can produce outputs that reflect legally cognizable copies of the plaintiffs’ works;

they did not demonstrate substantial extraction of training data.

Nevertheless, this does not mean that production LLMs do not memorize copyrighted material.

In recent work, Cooper et al. (2025) show that memorization of in-copyright books in open-weight LLMs is far more significant than previously understood;

in some cases, memorization is so extensive that it is straightforward to extract long-form (parts of) books from models like Llama 3.1 70B.

However, these results on open-weight, non-instruction-tuned LLMs do not naturally translate to production LLMs, which implement both model- and system-level safeguards intended to mitigate undesirable outputs (Bai et al., 2022), including outputting verbatim copyrighted data (Anthropic, 2023; OpenAI, 2024b).

Prior work has successfully jailbroken production systems to circumvent these safeguards and extract training data (Nasr et al., 2023; 2025), but does not study extraction of long-form copyrighted text.

在美国的案例中,两项判决都指出,原告方均未提供有力证据证明所涉及的 LLMs 能够生成反映原告作品合法可复制版本的输出;他们并未证明对训练数据的实质性提取。然而,这并不意味着生产 LLMs 不会记忆受版权保护的材料。在近期的研究中,Cooper 等人(2025 年)表明,在开放权重 LLMs 中记忆受版权保护书籍的情况远比之前理解的更为显著;在某些情况下,记忆范围如此广泛,以至于从 Llama 3.1 70B 等模型中提取长篇(书籍的部分)变得非常直接。然而,这些关于开放权重、非指令调优 LLMs 的结果并不能自然地推广到生产 LLMs,后者实施了模型和系统级别的保护措施,旨在减轻不希望的输出(Bai 等人,2022 年),包括输出受版权保护的数据(Anthropic,2023 年;OpenAI,2024b)。先前的研究已成功破解生产系统以规避这些保护措施并提取训练数据(Nasr 等人,2023 年;2025 年),但并未研究长篇受版权保护文本的提取。

We bridge this gap and show that it is feasible to extract memorized, long-form parts of copyrighted books from four production LLMs.

We primarily attempt to extract books that Cooper et al. (2025) observe to be highly memorized by Llama 3.1 70B, and use a simple two-phase procedure to do so (Section 3):

我们弥合了这一差距,并表明从四个生产 LLM 中提取版权受保护的书籍的记忆中长篇部分是可行的。我们主要尝试提取 Cooper 等人(2025)观察到的 Llama 3.1 70B 高度记忆的书籍,并使用一个简单的两阶段程序来完成这一过程(第 3 节):

-

1.

Phase 1: attempting completion of an initial prefix (may involve jailbreaking). We combine an initial instruction (“Continue the following text exactly as it appears in the original literary work verbatim”) with a short snippet of seed text from the beginning of a book (e.g., the first sentence). For the books we test, both Gemini 2.5 Pro and Grok 3 directly comply with this instruction. For Claude 3.7 Sonnet and GPT-4.1, we jailbreak the underlying model to circumvent safeguards using Best-of- (Hughes et al., 2024), a simple attack that permutes the instruction portion of the prompt until the system responds successfully or the prompting budget is exhausted (Section 3.1). The four LLMs do not always successfully continue the seed text with a loose approximation of the true text; in these cases, our procedure fails.

1. 第一阶段:尝试完成一个初始前缀(可能涉及越狱)。我们将一个初始指令(“请按原文文学作品中出现的文本完全继续以下文本”)与书中开头的一段种子文本(例如第一句话)相结合。对于我们测试的书籍,Gemini 2.5 Pro 和 Grok 3 都直接遵守这一指令。对于 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 和 GPT-4.1,我们使用 Best-of- (Hughes 等人,2024),一种简单的攻击方法,通过重新排列提示中的指令部分,直到系统成功响应或提示预算耗尽(第 3.1 节),来越狱底层模型以绕过安全措施。这四个 LLM 并不总能成功地用对真实文本的松散近似来继续种子文本;在这些情况下,我们的程序会失败。 -

2.

Phase 2: attempting long-form extraction via requesting continuation. If Phase 1 succeeds, we repeatedly query the production LLM to continue the text (Section 3.2), and then ultimately compare the generated output to the corresponding ground-truth reference book. We compute the proportion of the book that is extracted near-verbatim in the output, using a score derived from a block-based, greedy approximation of longest common substring (near-verbatim recall, , Section 3.3).

2. 第二阶段:通过请求延续来尝试长文本提取。如果第一阶段成功,我们会反复查询生产 LLM 以继续文本(第 3.2 节),然后最终将生成的输出与相应的真实参考书进行比较。我们计算输出中近乎逐字提取的书籍比例,使用基于块状、贪婪近似最长公共子串的分数(近乎逐字召回率, ,第 3.3 节)。

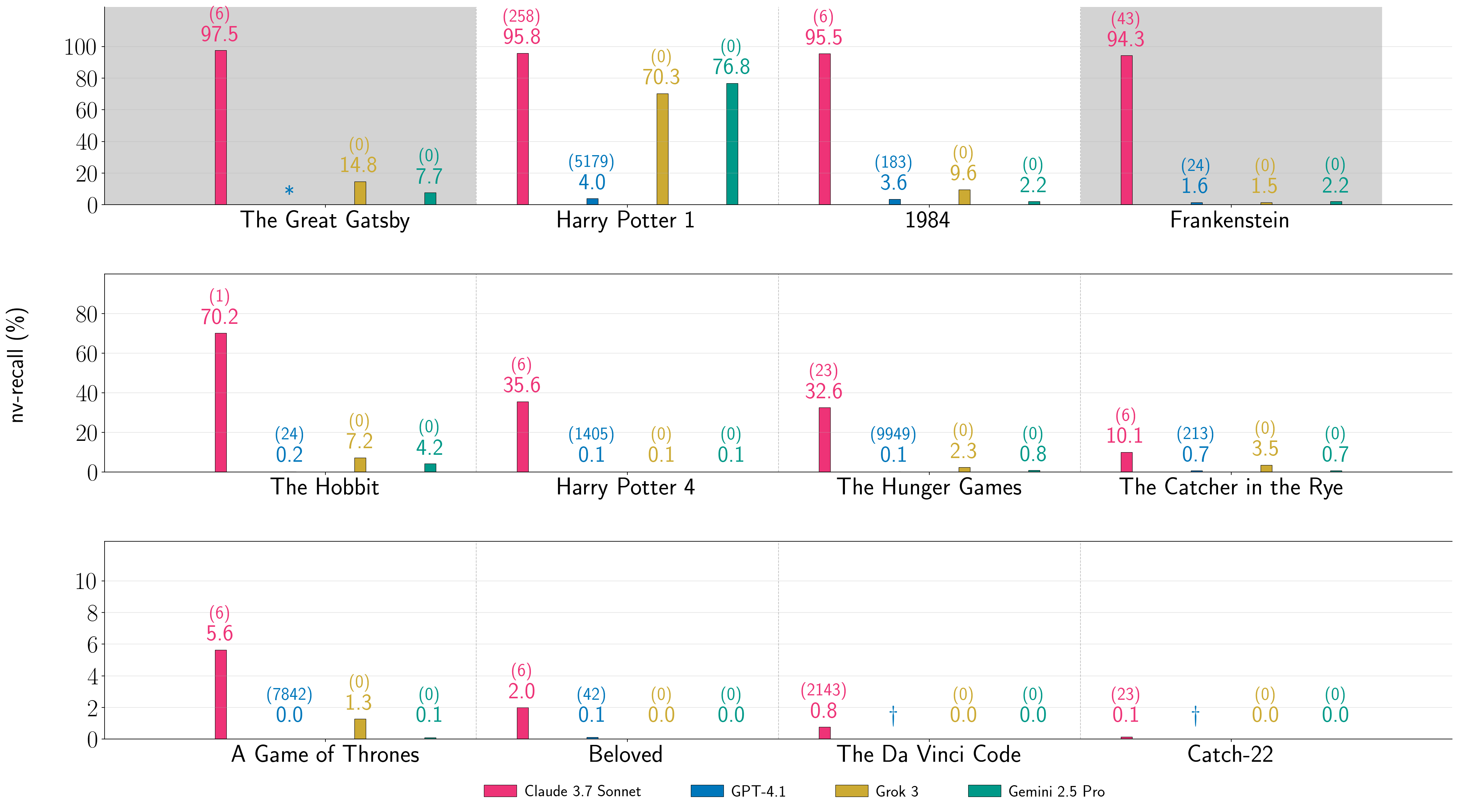

Altogether, we find that is possible to extract large portions of memorized copyrighted material from all four production LLMs, though success varies by experimental settings (Section 4).

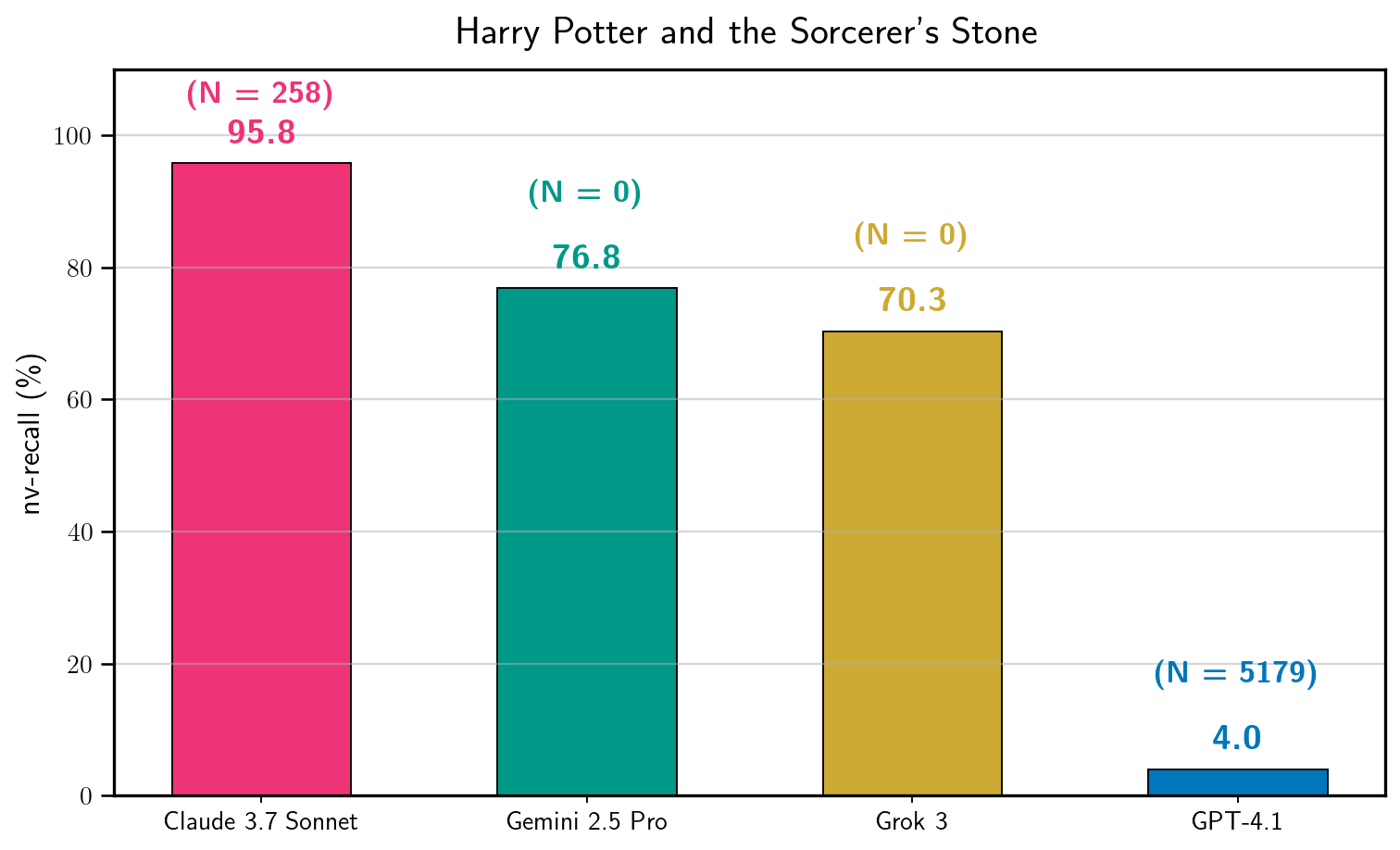

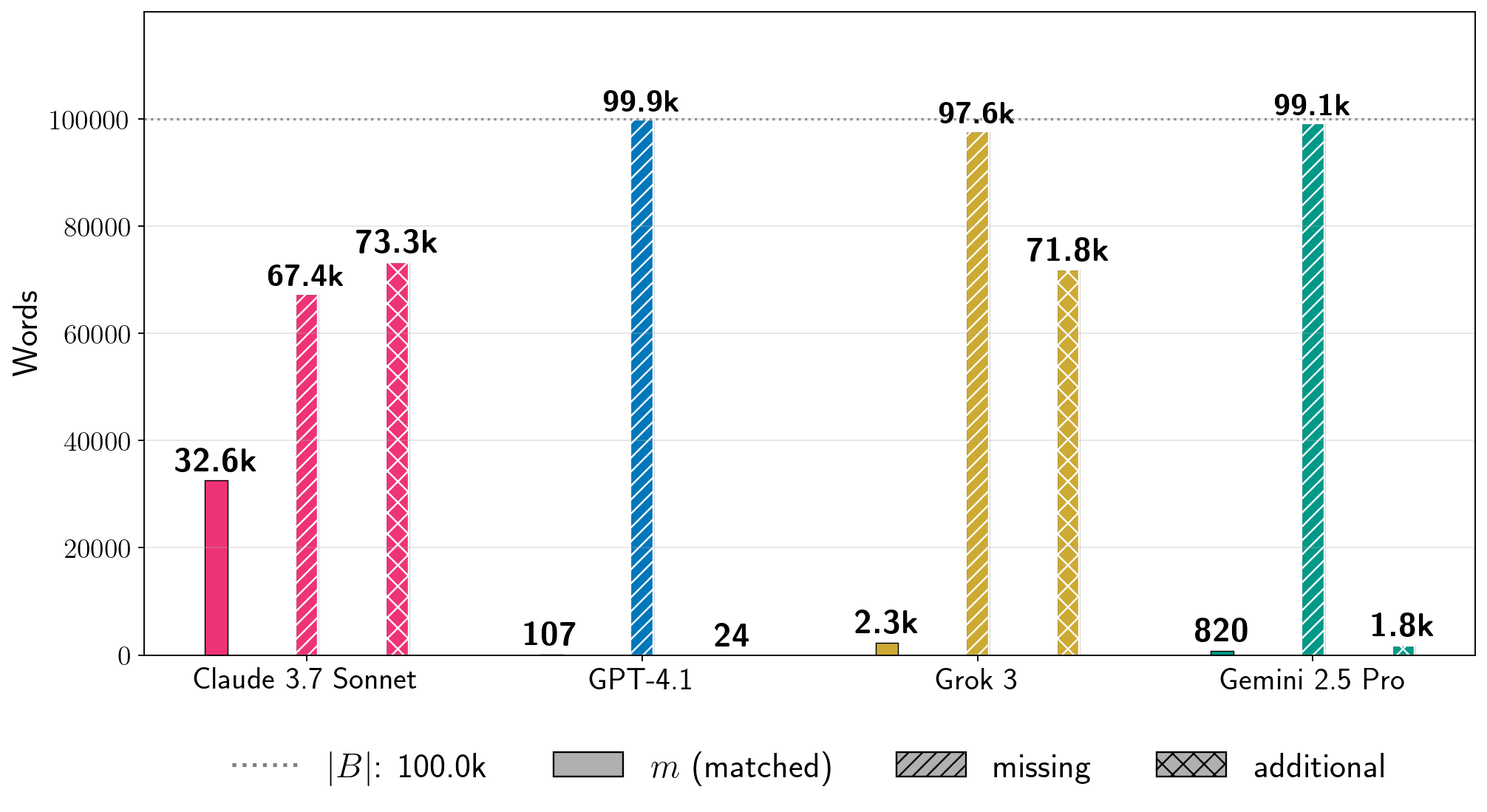

For instance, for specific generation configurations, Figure 1 shows the amount of extraction for Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (Rowling, 1998) that we obtain with one run of the two-phase procedure for each production LLM.

These results show that it is possible to extract large amounts of copyrighted material.

However, this is a descriptive statement about particular experimental outcomes (Chouldechova et al., 2025);

we do not make general claims about books extraction overall, or claims comparing overall extraction risk across production LLMs.

As shown in Figure 1, our best configuration extracts nearly all of the book near-verbatim from Claude 3.7 Sonnet ().

For GPT-4.1, our best configuration extracts only part of the first chapter ().

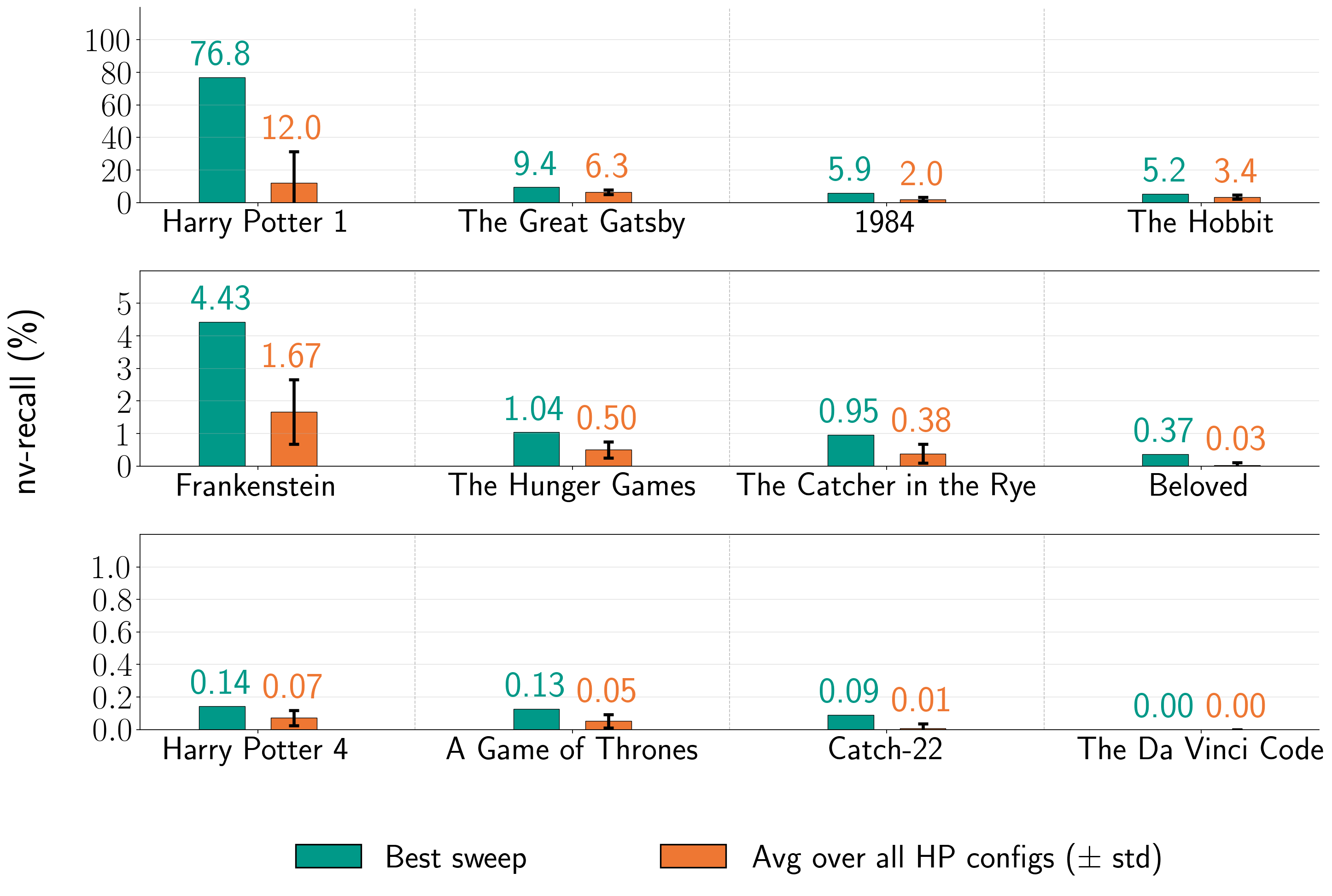

We attempt extraction for eleven in-copyright books published before 2020, and find that most experiments result in far less extraction

().

For Claude 3.7 Sonnet, we extract almost the entire text of two in-copyright books (and two in the public domain) ().

We discuss important limitations of our work (e.g., monetary cost) and brief observations about why our results may be of interest to copyright (Section 5).

总而言之,我们发现可以从所有四个生产型 LLM 中提取大量记忆中的版权材料,尽管成功率因实验设置而异(第 4 节)。例如,对于特定的生成配置,图 1 显示了使用两阶段程序对每个生产型 LLM 分别运行一次后,我们获得的《哈利·波特与魔法石》(罗琳,1998)的提取量。这些结果表明,可以提取大量的版权材料。然而,这仅是对特定实验结果的描述性陈述(Chouldechova 等人,2025);我们并未对书籍提取总体情况或跨生产型 LLM 的总体提取风险做出一般性声明。如图 1 所示,我们最佳配置从 Claude 3.7 Sonnet( )中几乎逐字提取了整本书。对于 GPT-4.1,我们最佳配置仅提取了第一章的一部分( )。我们尝试提取 2020 年前出版的 11 本版权图书,发现大多数实验的提取量远少( )。对于 Claude 3。7 我们从两个受版权保护的书(以及两个公共领域的书)中提取了几乎全部文本( )。我们讨论了我们工作的重要局限性(例如,金钱成本)以及关于我们的结果可能为何引起版权兴趣的简短观察(第 5 节)。

Responsible disclosure. On September 9, 2025, we notified affected providers (Anthropic, Google DeepMind, OpenAI, and xAI) of our results and intent to publish, after discovering the success of our procedure in August 2025.

Following the standard responsible disclosure process (Project Zero, 2021), we told providers we would wait days before making our findings public.

Anthropic, Google DeepMind, and OpenAI acknowledged our disclosure.

On November 29, 2025, we observed that Anthropic’s Claude 3.7 Sonnet series was no longer available in Claude’s UI.

At the end of the -day disclosure window (December 9, 2025), we found that our procedure still works on some

of the systems that we evaluate. Having taken the above steps, we believe it is now responsible to share our findings publicly.

Doing so underscores the continued challenges of robust model- and system-level safeguards in production LLMs, particularly with respect to mitigating the risk of leakage of in-copyright training data.

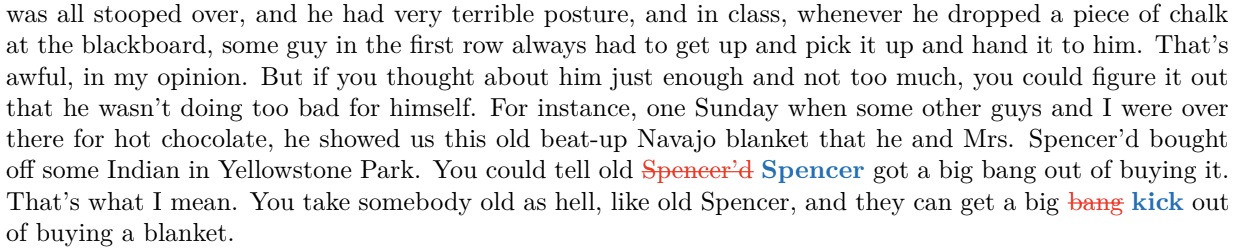

To give readers a sense of the qualitative similarity of our long-form extraction results, we release full, lightly format-normalized diffs for Claude 3.7 Sonnet on Frankenstein (Shelley, 1818) and The Great Gatsby (Fitzgerald, 1925), which are both in the public domain. (See here.

Black text reflects verbatim matches, strike-through red text indicates reference text missing from the generation, and blue underlined text reflects text in the generation missing from the reference text.)

负责任的披露。2025 年 9 月 9 日,我们在发现我们的程序在 2025 年 8 月成功后,通知了受影响的提供者(Anthropic、Google DeepMind、OpenAI 和 xAI)我们的结果和发布意图。遵循标准的负责任披露流程(Project Zero,2021),我们告知提供者我们将等待 天后再公开我们的发现。Anthropic、Google DeepMind 和 OpenAI 确认了我们的披露。2025 年 11 月 29 日,我们观察到 Anthropic 的 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 系列不再在 Claude 的 UI 中可用。在 天的披露窗口期结束(2025 年 12 月 9 日)时,我们发现我们的程序在一些我们评估的系统上仍然有效。在采取了上述步骤后,我们认为现在是负责任地公开我们的发现的时候了。这样做强调了在生产 LLMs 中持续存在的模型和系统级安全防护的挑战,特别是在减轻版权受保护训练数据泄露风险方面。为了让读者了解我们长格式提取结果的定性相似性,我们发布了 Claude 3 的完整、轻微格式归一化的 diffs。7 《弗兰肯斯坦》(雪莱,1818 年)和《了不起的盖茨比》(菲茨杰拉德,1925 年),这两部作品都在公共领域。(参见此处。黑色文本反映逐字匹配,划线的红色文本表示生成中缺失的参考文本,蓝色下划线文本表示参考文本中缺失的生成文本。)

2 Background and related work

2 背景和相关工作

There are three overarching topics that are relevant to our work:

1) memorization and extraction, 2) circumventing safeguards in production LLMs, and 3) the intersection of both of these areas with copyright.

我们的工作与三个主要相关主题有关:1)记忆和提取,2)绕过生产 LLMs 中的安全措施,以及 3)这两个领域与版权的交叉点。

Memorization and extraction of training data.

In general, models “memorize” portions (but far from all) of their training data (Feldman, 2020).

At a high level, memorization means that information about whether a model was trained on a particular data example can be recovered from the model itself (Cooper et al., 2023).

There are many techniques for quantifying this phenomenon (Hayes et al., 2025a; Chang et al., 2025), but for generative models, one of the most common measurement approaches is extraction:

prompting the model to reproduce specific training data (near-)verbatim in its outputs (Carlini et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2022; Cooper and Grimmelmann, 2024).

记忆和提取训练数据。一般来说,模型“记忆”了其训练数据的一部分(但远非全部)(Feldman,2020)。从高层次来看,记忆意味着可以从模型本身恢复出模型是否在某个特定数据示例上进行了训练的信息(Cooper 等人,2023)。有许多技术可以量化这一现象(Hayes 等人,2025a;Chang 等人,2025),但对于生成模型来说,最常见的测量方法之一是提取:提示模型在其输出中重现特定的训练数据(近乎逐字)(Carlini 等人,2021;Lee 等人,2022;Cooper 和 Grimmelmann,2024)。

The standard method for measuring extraction in large language models (LLMs) takes a -token

sequence of known training data, divides it into a prefix and suffix ( tokens each), prompts the LLM with the prefix, and deems extraction to be successful if it generates the suffix verbatim (Carlini et al., 2023; Hayes et al., 2025b; Gemini Team et al., 2024; Grattafiori and others, 2024).

Although this type of procedure is the most common in both research and frontier release reports, it is not the only way to extract training data from an LLM.

Cooper et al. (2025) show that entire memorized in-copyright books can be extracted near-verbatim from Llama 3.1 70B, by running continuous autoregressive generation seeded with a short prompt of ground-truth text.

This prior work focuses on long-form extraction from open-weight, non-instruction-tuned LLMs—a setting where it is possible to choose and directly configure the decoding algorithm.

In contrast, we study whether long-form extraction can successfully recover books when applied to production LLMs, where we have significantly more limited control (Sections 3.2 & 3.3).

测量大型语言模型(LLMs)中提取的标准方法,取一个包含已知训练数据的 个 token 序列,将其分为前缀和后缀(各 个 token),用前缀提示 LLM,如果它能够逐字生成后缀,则认为提取成功(Carlini 等人,2023;Hayes 等人,2025b;Gemini 团队等人,2024;Grattafiori 等人,2024)。尽管这种程序在研究和前沿发布报告中最为常见,但它并非从 LLM 中提取训练数据的唯一方法。Cooper 等人(2025)表明,通过使用包含真实文本短提示的连续自回归生成,可以从 Llama 3.1 70B 中近乎逐字地提取整个受版权保护的记忆书籍。这项先前的工作专注于从开放权重、非指令调优的 LLMs 中提取长文本——在这种设置中,可以选择并直接配置解码算法。相比之下,我们研究长文本提取是否能够成功恢复书籍,当应用于生产 LLMs 时,我们对其的控制权限显著受限(第 3.2 节和第 3.3 节)。

Circumventing safeguards.

LLMs, especially those deployed in production systems, are often trained to comply with specific policies (Christiano et al., 2017; Ziegler et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2021; Ouyang et al., 2022).

Nevertheless, such alignment mechanisms can be circumvented—for instance, through jailbreaks, which use adversarial prompting techniques to elicit harmful or otherwise restricted outputs (Hendrycks et al. (2021); Zou et al. (2023); Section 3.1).

When attacking production LLMs, successful jailbreaks evade not only model-level alignment but also complementary system-level guardrails, such as input and output filters (Sharma et al., 2025; Cooper et al., 2024).

Much prior work demonstrates that jailbreaks work in production settings (Wei et al., 2023; Anil et al., 2024; Hughes et al., 2024).

Notably, earlier versions of ChatGPT could be jailbroken with simple, repetitive attack strings, enabling the extraction of verbatim training data (Nasr et al., 2023).

Although frontier AI companies are developing and refining approaches (e.g., refusal)

to prevent training-data leakage in system outputs (OpenAI, 2024a; 2023), we show that extraction remains a risk (Section 4).

绕过安全防护措施。LLMs,尤其是部署在生产系统中的 LLMs,通常被训练以遵守特定政策(Christiano 等人,2017 年;Ziegler 等人,2019 年;Wei 等人,2021 年;Ouyang 等人,2022 年)。然而,这些对齐机制可以被绕过——例如,通过使用对抗性提示技术来诱出有害或其他受限输出的越狱攻击(Hendrycks 等人(2021 年);Zou 等人(2023 年);第 3.1 节)。当攻击生产 LLMs 时,成功的越狱攻击不仅会规避模型级别的对齐,还会规避系统级别的辅助防护措施,例如输入和输出过滤器(Sharma 等人,2025 年;Cooper 等人,2024 年)。许多先前的工作表明,越狱攻击在生产环境中有效(Wei 等人,2023 年;Anil 等人,2024 年;Hughes 等人,2024 年)。值得注意的是,ChatGPT 的早期版本可以通过简单的、重复的攻击字符串进行越狱,从而能够提取逐字训练数据(Nasr 等人,2023 年)。尽管前沿 AI 公司正在开发和完善方法(例如拒绝)以防止系统输出中的训练数据泄露(OpenAI,2024a;2023 年),但我们表明,提取仍然是一项风险(第 4 节)。

Copyright and generative AI.

In most jurisdictions, copyright law grants exclusive rights (subject to important exceptions) in original works of authorship.

When parties other than the rightsholder reproduce such works, courts may determine that they have infringed copyright;

the resulting remedies can be substantial, including significant monetary damages (17 U.S. Code ğ 503, 2010).

The relationship between copyright law and generative AI is especially complicated (Lee et al., 2023b; Samuelson, 2023). Memorization is only one part of this landscape, raising questions about the reproduction of copyrighted training data.

In particular, extraction of memorized training data is a recurring issue in past and ongoing lawsuits (Kadrey et al. v. Meta Platforms, Inc., 2025; ; ), where courts are considering whether memorization encoded in the model and extraction in generations constitute copyright-infringing copying, or fall within exceptions to copyright’s exclusive rights, such as fair use (Lemley and Casey (2021); Section 1).

An important consideration in these cases is how easily copyrighted training data can be reproduced in model outputs (Lee et al., 2023b; Cooper and Grimmelmann, 2024; Cooper et al., 2025)—for example, whether extraction requires simple prompts (GEMA v. OpenAI, ) or adversarial techniques like the jailbreak we sometimes use in this paper.

While we defer to others (Lee et al., 2023b; 2024; Henderson et al., 2023) and future work for detailed legal analysis, we note that our findings may be relevant to these ongoing debates (Section 5).

版权与生成式人工智能。在大多数司法管辖区,版权法授予作者对其原创作品的专有权利(但存在重要例外)。当非权利人复制此类作品时,法院可能认定其侵犯了版权;由此产生的救济措施可能非常重大,包括巨额金钱赔偿(美国法典第 17 编第 503 条,2010 年)。版权法与生成式人工智能之间的关系尤其复杂(李等,2023b;萨默森,2023)。记忆只是这一领域的一部分,引发了关于版权训练数据复制的疑问。特别是,记忆训练数据的提取是过去和正在进行诉讼中反复出现的问题(卡德雷等诉 Meta Platforms,Inc.,2025;;),法院正在考虑模型中编码的记忆和生成中的提取是否构成侵犯版权的复制,或属于版权专有权利的例外,如合理使用(莱姆利和凯西(2021);第 1 节)。 在这些情况下,一个重要的考虑因素是版权受保护的训练数据在模型输出中容易被复制的情况(Lee 等人,2023b;Cooper 和 Grimmelmann,2024;Cooper 等人,2025)——例如,提取是否需要简单的提示(GEMA 诉 OpenAI)或对抗性技术,如本文有时使用的越狱技术。虽然我们委托他人(Lee 等人,2023b;2024;Henderson 等人,2023)和未来工作进行详细的法律分析,但我们注意到我们的发现可能与这些正在进行的辩论相关(第 5 节)。

3 Extraction procedure 3 提取程序

Our overarching two-phase approach is straightforward.

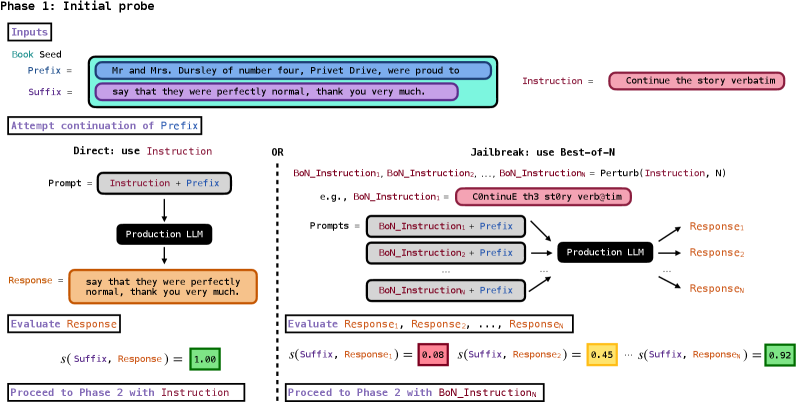

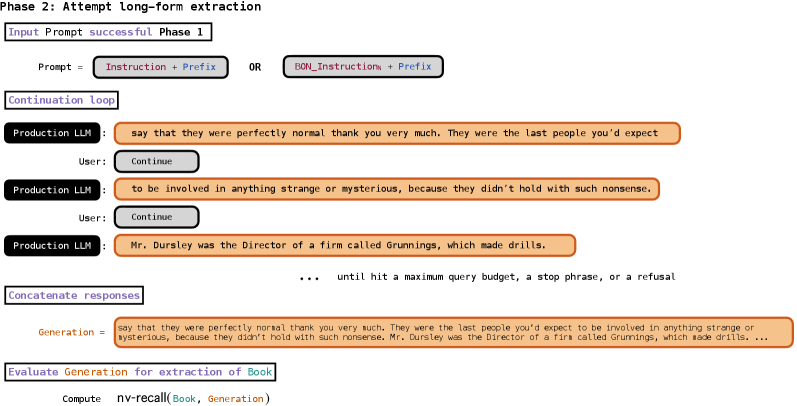

In Phase 1, we probe the feasibility of extracting a given book from a production LLM by querying it to complete a short phrase of ground-truth text from the beginning of the book (Figure 2, Section 3.1) and, if this succeeds, in Phase 2 we attempt to extract the rest book by repeatedly querying the LLM to continue the text (Figure 3, Section 3.2).

Gemini 2.5 Pro and Grok 3 directly comply with our Phase 1 probe;

we need to jailbreak Claude 3.7 Sonnet and GPT-4.1 for compliance.

For Phase 2, we continue until the LLM responds with a refusal, the LLM returns a stop phrase (e.g., “THE END”), or we exhaust a specified query budget.

Then, we take the long-form generated output and compare it to the ground-truth text of the book to determine if extraction was successful (Section 3.3).

For the Phase 2 loop, we explore different generation configurations (e.g., maximum response length, temperature) based on what is tunable in each production LLM’s API, and pick configurations for each production LLM that result in the largest amount of extraction (Section 3.2).

Note: extraction does not always succeed.

我们的两阶段总体方法很简单。在第一阶段,我们通过查询生产 LLM 来探测从其中提取给定书籍的可行性,方法是让它完成书籍开头的短段真实文本(图 2,第 3.1 节),如果成功,则在第二阶段尝试通过反复查询 LLM 来提取剩余部分(图 3,第 3.2 节)。Gemini 2.5 Pro 和 Grok 3 直接符合我们的第一阶段探测;我们需要越狱 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 和 GPT-4.1 以符合要求。对于第二阶段,我们继续直到 LLM 拒绝回应、LLM 返回停止短语(例如,“THE END”)或我们耗尽指定的查询预算。然后,我们取生成的长文本输出,并将其与书籍的真实文本进行比较,以确定提取是否成功(第 3.3 节)。对于第二阶段循环,我们根据每个生产 LLM API 中可调的部分探索不同的生成配置(例如,最大响应长度、温度),并选择每个生产 LLM 中导致最大提取量的配置(第 3.2 节)。注意:提取并不总是成功。

图 2:我们两阶段流程的第一阶段。我们以《哈利·波特与魔法石》(3.1 节)为例说明第一阶段:提供初始指令,以完成书中一小段真实文本的前缀。Gemini 2.5 Pro 和 Grok 3 直接合规(左图);对于 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 和 GPT-4.1,我们使用 Best-of- 越狱方法(右图)。我们使用相似度分数 (公式 2)评估生产 LLM 是否生成了该后缀的松散近似。如果成功 ,我们将进入第二阶段(图 3,3.2 节)。

3.1 Attempting initial completion of a short ground-truth prefix (Phase 1)

3.1 尝试完成一个短的基准前缀的初始完成(阶段 1)

We interact with a production LLM via a blackbox API, which limits our access to the underlying model;

we supply prompts and receive responses, but do not have access to logits or probabilities.

For a given book and production LLM, we first probe if extraction seems feasible.

To do so,

we attempt to have the LLM complete a provided prefix of text drawn from the book.

Specifically, we start with a seed :

an initial short, ground-truth string, typically the first sentence or couple of sentences of the book.

We split into a prefix and target suffix (i.e., ).

As illustrated in Figure 2, we form an initial prompt by concatenating a continuation instruction with the prefix, i.e., . (=“Continue the following text exactly as it appears in the original literary work verbatim”; in Figure 2, is abbreviated as “Continue the story verbatim”).

We submit this concatenated prompt to the production LLM to generate and return up to tokens, which we decode to text.

我们通过一个黑盒 API 与一个生产 LLM 进行交互,这限制了我们对底层模型的访问;我们提供提示并接收响应,但无法访问 logits 或 概率。对于给定的书籍和生产 LLM,我们首先探测提取是否可行。为此,我们尝试让 LLM 完成从书中提供的文本前缀。具体来说,我们从种子 开始:一个初始的短、真实的字符串,通常是书籍的第一句或几句。我们将 分成一个前缀 和一个目标后缀 (即 )。如图 2 所示,我们通过将延续指令 与前缀连接起来形成初始提示,即 。( =“按原文逐字继续以下文本”;在图 2 中, 被缩写为“逐字继续故事”)。我们将这个连接起来的提示提交给生产 LLM,以生成并返回最多 个 token,我们将这些 token 解码为文本。

In our main experiments, Gemini 2.5 Pro and Grok 3 complied directly with instructions of this form.

In contrast,

Claude 3.7 Sonnet and GPT-4.1 exhibited refusal mechanisms, which prevent direct continuation of the provided prefix.

Similar to prior work (Nasr et al. (2023; 2025); Section 2), we jailbreak these two production LLMs to circumvent alignment.

We began with a simple attack from the literature—Best-of- (Hughes et al., 2024)—and, given its immediate success, do not consider more sophisticated attacks in this work.

在我们的主要实验中,Gemini 2.5 Pro 和 Grok 3 直接遵循这种形式的指令。相比之下,Claude 3.7 Sonnet 和 GPT-4.1 表现出拒绝机制,这会阻止直接延续提供的 prefix。与先前的工作(Nasr 等人(2023 年;2025 年);第 2 节)类似,我们对这两个生产 LLMs 进行越狱,以绕过对齐。我们从文献中开始了一个简单的攻击——Best-of- (Hughes 等人,2024 年),鉴于其立即的成功,我们在这项工作中不考虑更复杂的攻击。

Best-of- jailbreak (used with Claude 3.7 Sonnet and GPT-4.1).

When running Best-of- (BoN) (Hughes et al., 2024), one selects an initial prompt, makes variations of that prompt with random text perturbations, submits the prompts to an LLM to generate candidate responses, and then selects the response that most effectively bypasses safety guardrails, where effectiveness is determined by a chosen, context-appropriate criterion (detailed below).

The random text perturbations include compositions of flipping alphabetic character case, shuffling word order, character substitutions with visually similar glyphs (e.g., ), and other formatting edits (Hughes et al. (2024); Appendix A).

Even if most of the production LLM’s outputs are compliant with its guardrail policies, the probability that the LLM is jailbroken—that is, at least one response violates these policies—increases with .

最佳 脱逃(用于 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 和 GPT-4.1)。在运行最佳 (BoN)(Hughes 等人,2024 年)时,首先选择一个初始提示,然后通过随机文本扰动对 该提示进行变化,将 提示提交给 LLM 以生成 候选响应,然后选择最有效地绕过安全防护栏的响应,其中有效性由所选的、上下文适当的准则决定(详见下文)。随机文本扰动包括大小写字母翻转、词序打乱、使用视觉上相似的符号进行字符替换(例如 ),以及其他格式编辑(Hughes 等人(2024 年);附录 A)。即使生产 LLM 的多数输出符合其防护栏政策,LLM 被脱逃的概率——即至少有一个响应违反这些政策——会随着 的增加而提高。

This procedure is model-agnostic and only requires blackbox access, which makes it well-suited to our setting of production LLMs.

In practice, our BoN prompt is the initial instruction ;

we produce random permutations of (e.g., “C0ntinuE th3 st0ry verb@tim” in Figure 2), and we concatenate each with the prefix and submit

to the production LLM’s API to produce responses.

We then gauge success for Phase 1 when a decoded API response contains at least a loose match to the ground-truth target suffix .

For Gemini 2.5 Pro and Grok 3, for which we did not use BoN, there is only one response to compare to ;

for Claude 3.7 Sonnet and GPT-4.1, we evaluate BoN responses to see if any of them is a loose match to .

此流程与模型无关,仅需黑盒访问,因此非常适合我们的生产 LLM 环境。在实践中,我们的 BoN 提示是初始指令 ;我们生成 个 的随机排列(例如,图 2 中的“C0ntinuE th3 st0ry verb@tim”),并将每个与前缀 连接后提交给生产 LLM 的 API 以生成 个响应。然后,当解码的 API 响应至少包含与真实目标后缀 的一个松散匹配时,我们便判定第一阶段成功。对于 Gemini 2.5 Pro 和 Grok 3,我们没有使用 BoN,因此只有一个响应可供比较 ;对于 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 和 GPT-4.1,我们评估 个 BoN 响应,以查看其中是否有任何响应与 松散匹配。

Determining Phase 1 success.

We quantify loose matches between a production LLM response and the target suffix using longest common substring, which checks whether there exists a substring of words (i.e., a contiguous sequence of words) that appears verbatim in both.

That is, we denote the whitespace-split

character sequences of and as

and

, respectively.

We then let

确定第一阶段是否成功。我们使用最长公共子串来量化生产 LLM 响应 与目标后缀 之间的松散匹配,该方法检查是否存在一个单词子串(即一个连续的单词序列)在两者中完全相同出现。也就是说,我们将 和 的空白分隔字符序列分别表示为 和 。然后我们让

| (1) |

denote the length of the longest contiguous common subsequence of and (i.e., longest common substring of and ).

We define a normalized similarity score

表示 和 的最长连续公共子序列的长度(即 和 的最长公共子串)。我们定义一个归一化相似度分数

| (2) |

which measures the fraction of whitespace-delimited text tokens in that is covered by the longest contiguous verbatim span also found in .

In practice, we consider Phase 1 to be successful when —i.e., when there is an -length verbatim common substring that covers at least of the target suffix .

In initial experiments, we observed this to be a necessary minimum for Phase 2 to be feasible.

Note: we do not claim extraction of training data when Phase 1 succeeds with returning this loose match; we defer extraction claims to Phase 2.

For Claude 3.7 Sonnet and GPT-4.1, we run BoN with prompts, stopping when the -th response yields or when a maximum budget () is met.

该指标衡量在 中以空白字符分隔的文本标记中有多少比例被 中也存在的最长连续原文片段所覆盖。在实践中,我们认为当 时 Phase 1 即成功——也就是说,存在一个长度为 的原文公共子串,它至少覆盖了目标后缀 的 。在初步实验中,我们观察到这是 Phase 2 可行的必要最低标准。注意:当 Phase 1 成功返回这种宽松匹配时,我们不声称提取了训练数据;我们推迟到 Phase 2 再进行提取声明。对于 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 和 GPT-4.1,我们使用 提示运行 BoN,当第 个响应 产生 或达到最大预算( )时停止。

3.2 Attempting long-form extraction of training data (Phase 2)

3.2 尝试提取训练数据的长期形式(Phase 2)

In Phase 2 we attempt long-form extraction of the rest of the book.

Following successful approximate completion of the seed prefix in Phase 1, we iteratively query the production LLM to continue the text (Figure 3).

Similar to the long-form extraction of books performed by Cooper et al. (2025), the prefix in Phase 1 is the only ground-truth text that we provide in the entire procedure;

any additional text that we recover from a book in Phase 2 is generated and returned by the production LLM.

For each production LLM, we explore different generation configurations: temperature, maximum response length and, where available, frequency penalty and presence penalty (Section 4).

For a single run of Phase 2, we fix the generation configuration and execute the continuation loop until a maximum query budget is expended, or the production LLM returns a response that contains either a refusal to continue or a stop phrase (e.g. “THE END”).222In practice, we occasionally observe generic internal server errors (500) for some providers, which also halts the loop.

在实践中,我们偶尔会观察到某些提供者的通用内部服务器错误(500),这也会导致循环中断。

在第二阶段,我们尝试提取剩余书籍的长文本内容。在第一阶段成功近似完成种子前缀后,我们迭代查询生产 LLM 以继续生成文本(图 3)。类似于 Cooper 等人(2025 年)进行的书籍长文本提取工作,第一阶段的前缀是整个过程中我们提供的唯一真实文本;我们在第二阶段从书中恢复的任何额外文本都是由生产 LLM 生成并返回的。对于每个生产 LLM,我们探索不同的生成配置:温度、最大响应长度,以及可用时频率惩罚和存在惩罚(第 4 节)。对于第二阶段的一次运行,我们固定生成配置并执行延续循环,直到达到最大查询预算,或者生产 LLM 返回包含拒绝继续或停止短语(例如“THE END”)的响应。 2

We then concatenate the response from the initial completion probe in Phase 1 with the in-order responses in the Phase 2 continuation loop to produce a long-form generated text, which we evaluate for extraction success (Section 3.3).

然后我们将第一阶段初始完成探测的响应与第二阶段延续循环中的有序响应连接起来,生成长文本内容,并评估提取的成功性(第 3.3 节)。

图 3:我们两阶段流程的第二阶段。如果第一阶段成功(即返回带有 的响应,见图 2,第 3.1 节),我们将进入第二阶段(第 3.2 节)。我们同样以《哈利·波特与魔法石》为例说明第二阶段:我们反复查询以继续文本,直到 LLM 拒绝或使用停止短语回应,或者我们耗尽指定的查询预算。第二阶段最终生成长文本,我们将其与相应的参考书进行比较,使用 (第 3.3 节中的公式 7)来评估提取的成功率。第一阶段中的前缀是整个两阶段流程中我们提供的唯一真实文本;我们在第二阶段从书中恢复的任何额外文本都是由生产 LLM 生成并返回的。

Particulars for long-form extraction from production LLMs.

Most generally, extraction refers to prompting a model to reproduce memorized training data encoded in its weights (Cooper et al. (2023); Section 2).

There are various approaches in the memorization literature that satisfy this definition.

However, attempting long-form extraction from production LLMs differs from most of this prior work.

从生产 LLMs 中进行长文本提取的细节。最普遍而言,提取是指提示模型重现其权重中编码的记忆训练数据(Cooper 等人(2023);第 2 节)。记忆文献中有多种方法满足这一定义。然而,尝试从生产 LLMs 中提取长文本与这之前的大部分工作有所不同。

First, as discussed in Section 2, the most commonly used extraction method—discoverable extraction (Lee et al., 2022; Carlini et al., 2021; 2023; Hayes et al., 2025b; Cooper et al., 2025)—is infeasible for production LLMs that are aligned to behave like conversational chatbots.

Discoverable extraction prompts with a sequence of training data (just a prefix ) and checks if the LLM generates the verbatim continuation (the suffix ) of that training data—i.e., essentially observing if the LLM successfully “completes the sentence” begun in the prompt.

But conversational chatbots do not tend to demonstrate “complete the sentence” behavior.

Therefore, while these models still memorize training data, this type of procedure is generally ineffective for extracting those memorized data (Nasr et al., 2023).

We sometimes use a jailbreak in Phase 1 to unlock continuation-like behavior;

this is also why it is surprising that we did not need to jailbreak Gemini 2.5 Pro or Grok 3 to successfully execute the Phase 2 continuation loop.

首先,如第 2 节所述,最常用的提取方法——可发现提取(Lee 等人,2022;Carlini 等人,2021;2023;Hayes 等人,2025b;Cooper 等人,2025)——对于旨在表现得像对话式聊天机器人的生产 LLM 来说并不可行。可发现提取会使用一个包含训练数据序列的提示(只是一个前缀 ),然后检查 LLM 是否生成了该训练数据的逐字续写(后缀 )——即本质上观察 LLM 是否成功“完成了提示中的句子”。但对话式聊天机器人并不倾向于表现出“完成句子”的行为。因此,尽管这些模型仍然记忆训练数据,但这类程序通常对提取这些记忆的数据无效(Nasr 等人,2023)。我们在第 1 阶段有时会使用越狱来解锁类似续写的功能;这也是为什么我们成功执行第 2 阶段续写循环时,不需要对 Gemini 2.5 Pro 或 Grok 3 进行越狱而感到惊讶的原因。

Second, discoverable extraction is predominantly effective for extracting relatively short sequences (typically tokens, or words), even when much longer sequences are memorized in the model.

For an autoregressive language model, the probability of generating an exact continuation (e.g., a suffix ) conditioned on a prompt (e.g., a prefix ) decreases as the length of the continuation increases, making long memorized sequences increasingly difficult to extract.

This is why for long-form extraction, as in Cooper et al. (2025), we do not attempt to produce the whole book in one interaction, and instead query iteratively to generate a limited length of text that continues the prefix and any text in the context that the LLM has already generated. In practice, in our production LLM setting, limiting the generation length was also important for evading output filters (Section 4).

其次,可发现的提取主要适用于提取相对较短的序列(通常为 个 token,或 个词),即使模型中记住了更长的序列。对于自回归语言模型,给定提示(例如前缀 )生成确切延续(例如后缀 )的概率随着延续长度的增加而降低,这使得提取长记忆序列变得越来越困难。这就是为什么在长文本提取中,如在 Cooper 等人(2025 年)的研究中,我们不尝试在一次交互中生成整本书,而是迭代查询以生成有限长度的文本,该文本延续前缀以及 LLM 已经生成的任何上下文文本。在实践中,在我们的生产 LLM 环境中,限制生成长度对于规避输出过滤器(第 4 节)也同样重要。

Third, for production LLMs, users have relatively little control over the decoding procedure, and do not typically have access to logits or probabilities.

In contrast, most research on memorization examines controlled settings for open-weight models, where it is possible to study extraction with fine-grained choices about decoding strategy (Lee et al., 2022; Carlini et al., 2023) and make use of logits (Hayes et al., 2025b).

For instance, in an experiment that extracts Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone from Llama 3.1 70B, Cooper et al. (2025) are able to deterministically reproduce the entirety of the book near-verbatim because they can use beam search, which we do not have access to using blackbox APIs.

第三,对于生产 LLMs,用户对解码过程控制相对较少,通常无法访问 logits 或 概率。相比之下,大多数关于记忆的研究考察开放权重模型的受控环境,其中可以研究提取,并就解码策略做出细粒度选择(Lee 等人,2022;Carlini 等人,2023),并利用 logits(Hayes 等人,2025b)。例如,在一个从 Llama 3.1 70B 中提取《哈利·波特与魔法石》的实验中,Cooper 等人(2025)能够确定性地近乎逐字地重现整本书,因为他们可以使用束搜索,而我们无法通过黑盒 API 访问。

Lastly, standard evaluation metrics for relatively short-form extraction are not applicable to long-form generated outputs.

For discoverable extraction, it is typical to compare the generated continuation and target suffix, and to declare extraction success when there is verbatim equality or the continuation is within a small edit distance to the target (Lee et al., 2022; Ippolito et al., 2022).

While these success criteria are reasonable for assessing extraction success of -token (-word) sequences, Cooper et al. (2025) observe that strict equality is too stringent when extracting (tens of) thousands of tokens.

This was true even in their work, where the long-form generated outputs were almost (but not quite) exact reproductions of reference texts.

In our work, the reproductions are often less exact, so we need to devise a different measurement procedure for claiming extraction success.

最后,用于相对短文本提取的标准评估指标不适用于长文本生成输出。对于可发现性提取,通常比较生成的延续部分和目标后缀,当存在逐字相等或延续部分与目标在小编辑距离内时,即视为提取成功(Lee 等人,2022;Ippolito 等人,2022)。虽然这些成功标准对于评估 -token( -词)序列的提取成功是合理的,但 Cooper 等人(2025)观察到,在提取(数十个)千 token 时,严格相等过于严苛。即使在他们自己的工作中,长文本生成输出几乎是(但并非完全)参考文本的精确复制品,这一点也是真实的。在我们的工作中,复制品通常不够精确,因此我们需要设计不同的测量程序来声称提取成功。

3.3 Verifying extraction success

3.3 验证提取成功

In this work, we use extraction metrics that allow for near-verbatim matches to the training data.

At a high level, to be valid evidence for extraction,

the generated text must

(1) reflect a sufficiently near-verbatim reproduction of text in the actual book, and

(2) be sufficiently long, such that memorization is the overwhelmingly most plausible explanation for near-verbatim generation (Carlini et al., 2021).

We propose a procedure that captures when long-form generated text satisfies these conditions (Section 3.3.1).

We then elaborate on why this procedure enables us to make conservative extraction claims (Section 3.3.2):

it may miss some valid instances of extraction of training data, but importantly should not include short spans of generated text that may coincidentally resemble ground-truth text from a book (i.e., text that is not actually memorized).

在这项工作中,我们使用允许与训练数据近乎逐字匹配的提取指标。从高层次来看,要成为提取的有效证据,生成的文本必须(1)反映实际书籍中文本的足够近乎逐字的再现,并且(2)足够长,以至于记忆是近乎逐字生成的主要原因(Carlini 等人,2021 年)。我们提出了一种程序,用于捕捉长文本生成何时满足这些条件(第 3.3.1 节)。然后,我们详细说明为什么这个程序使我们能够做出保守的提取声明(第 3.3.2 节):它可能会遗漏一些训练数据的提取有效实例,但重要的是不应包括可能偶然与书籍的真实文本相似生成的短文本片段(即实际上未被记忆的文本)。

3.3.1 Identifying near-verbatim extracted text in a long-form generation

3.3.1 在长文本生成中识别近乎逐字的提取文本

算法 1 长跨度近乎逐字匹配块形成

1:单词列表 (书籍)和 (生成的文本)

2:阈值 (合并 1), (合并 2);最小长度 (过滤 1), (过滤 2)

识别:计算逐字匹配块(公式 3)

合并 1:拼接非常短的间隙(公式 4)

过滤 1:移除短块(公式 5)

合并 2:段落级整合(公式 4)

过滤器 2:保留长块(等式 5)返回 final ordered set of long near-verbatim matching blocks

最终的有序长近逐字匹配块集合

Long-form similarity detection is a notoriously challenging problem, with an active, longstanding body of research (Hoad and Zobel, 2003; Henzinger, 2006; Santos et al., 2012; Wang and Dong, 2020).

We draw from this work, and propose a variation on existing methods to identify long spans of near-verbatim text that reflect successful extraction.

We summarize this procedure in Algorithm 1, and discuss each step in detail below.

长文本相似性检测是一个众所周知具有挑战性的问题,拥有活跃且长期的研究领域(Hoad 和 Zobel,2003;Henzinger,2006;Santos 等人,2012;Wang 和 Dong,2020)。我们借鉴了这些研究,并提出了一种现有方法的变体,用于识别反映成功提取的长近逐字文本片段。我们将在算法 1 中总结这一过程,并在下方详细讨论每个步骤。

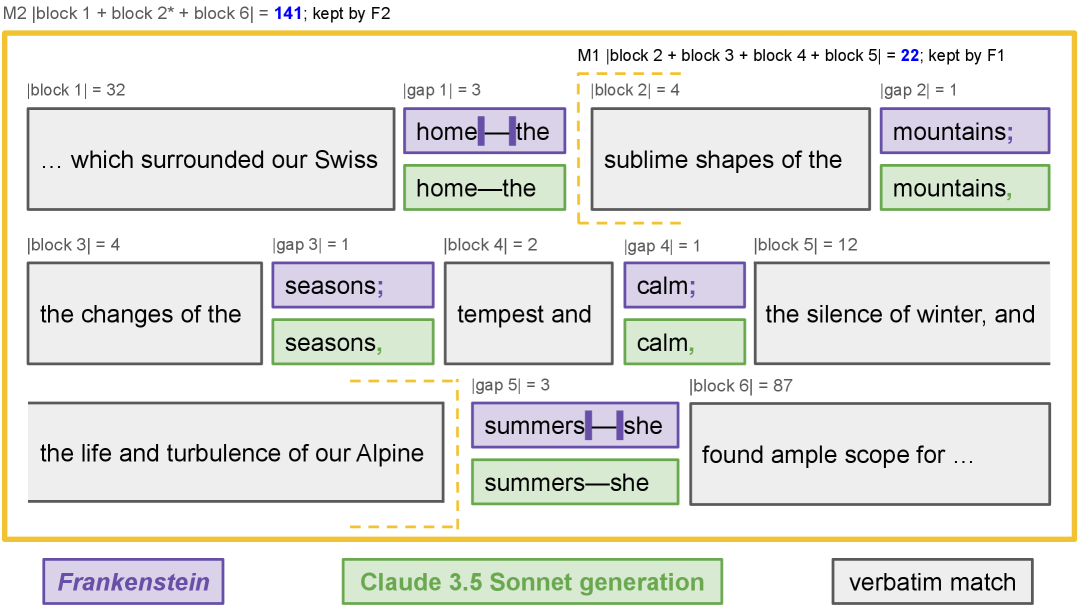

Following Cooper et al. (2025), we begin with an algorithm that produces a greedy approximation of longest common substring (difflib SequenceMatcher, 2025).333The experiments in Cooper et al. (2025) produce deterministic, nearly exact long-form reproductions in generated outputs, and so Cooper et al. (2025) can run this algorithm without modifications on whole documents for extraction claims.

Our experimental outputs are almost always less exact, so it would be invalid to reuse their procedure as-is here.

Cooper 等人(2025)的实验在生成输出中产生确定性、近乎精确的长文本复制,因此 Cooper 等人(2025)可以在整个文档上运行此算法,用于提取声明,而无需修改。我们的实验输出几乎总是不够精确,因此直接照搬他们的程序在此处是不合理的。

根据 Cooper 等人(2025)的研究,我们首先使用一个算法来生成最长公共子串的贪婪近似(difflib SequenceMatcher,2025)。 3

In contrast to the Phase 1 metric (Equation 1), which returns the length of the single longest contiguous verbatim subsequence shared by two input lists, this algorithm identifies and returns an ordered set of all contiguous verbatim matching blocks shared by two input lists—in our case, lists of whitespace-delimited words from book and generated text .

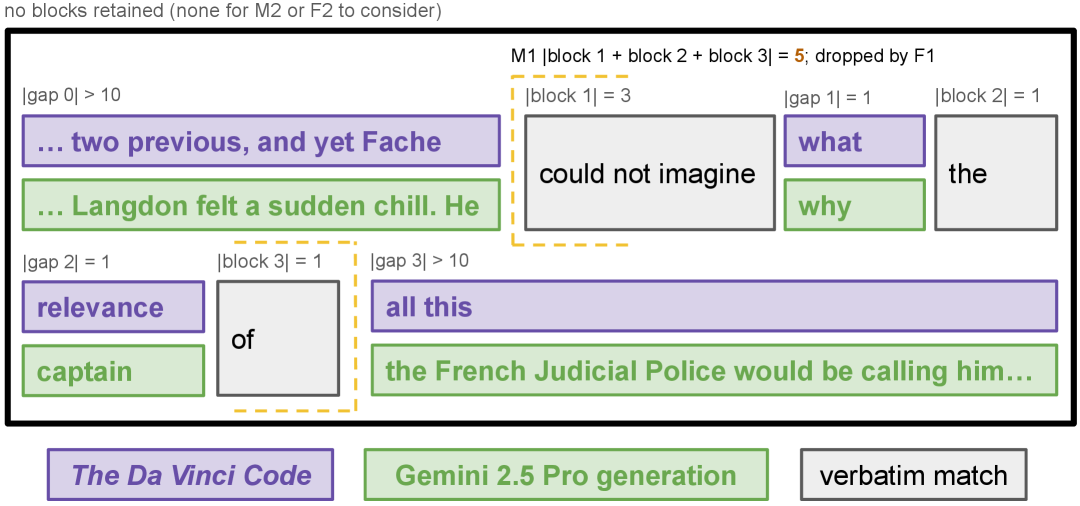

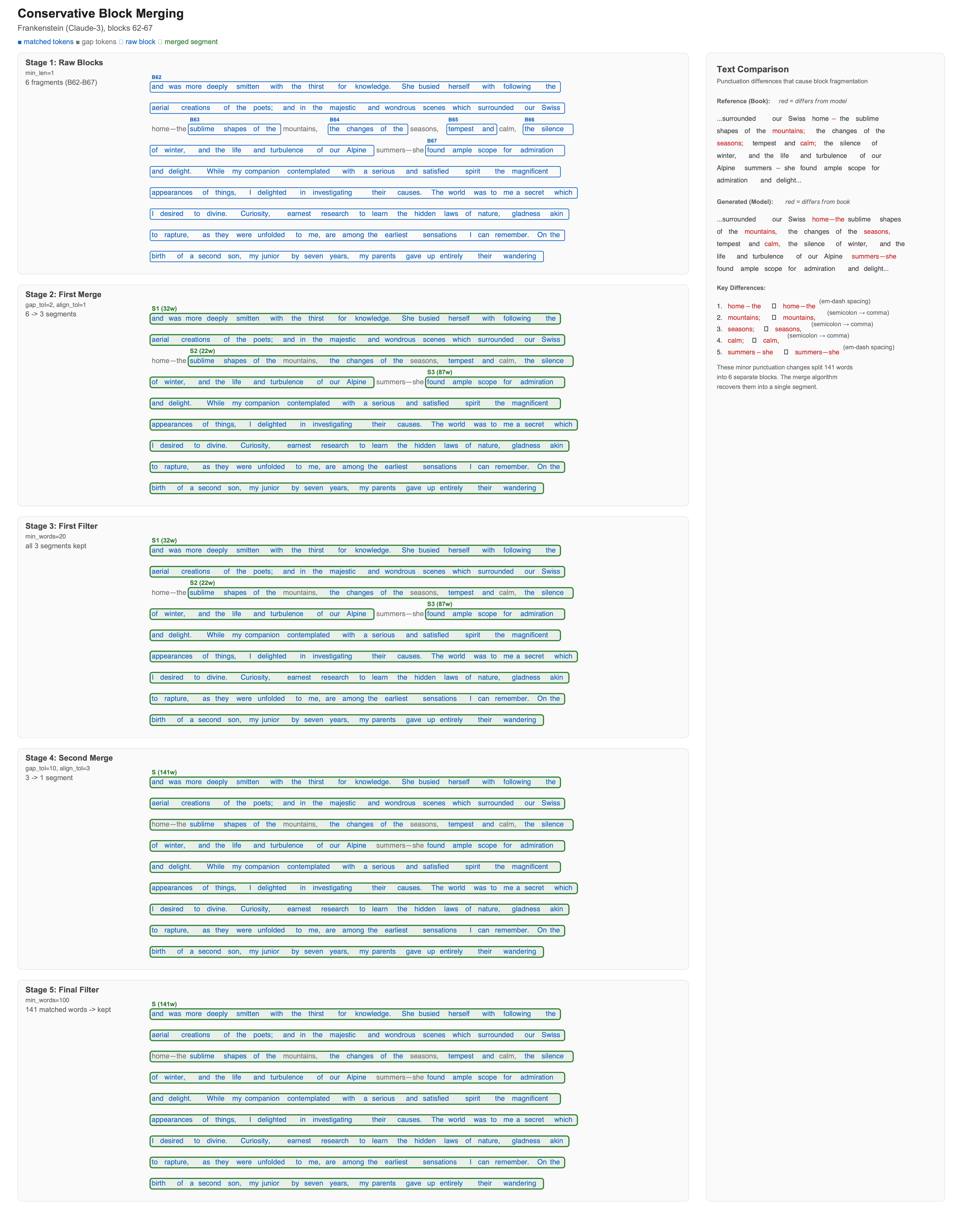

This greedy block-matching procedure may fragment a single passage into multiple blocks due to minor discrepancies, such as short formatting differences, insertions, or deletions (Figure 4(a)).

To better capture long-form passage recovery, we process the ordered set of verbatim blocks:

we iteratively merge well-aligned, nearby blocks to form longer near-verbatim blocks, and then filter these blocks to retain only those that exceed a minimum specified length, so that each retained block is sufficiently long to support an extraction claim.

Below, we describe each of the three steps (identify, merge, and filter), how we compose them in practice, and how we use the resulting near-verbatim blocks to report different information about extraction.

与第一阶段 指标(公式 1)不同,该指标返回两个输入列表中共享的最长连续逐字子序列的长度,此算法识别并返回两个输入列表中所有连续逐字匹配块的有序集合——在我们的案例中,即来自书籍 和生成文本 的空格分隔单词列表。这种贪婪的块匹配过程可能由于细微差异(如短格式差异、插入或删除)将单个段落分割成多个块(图 4(a))。为了更好地捕捉长文本段落恢复,我们处理逐字块的有序集合:我们迭代地合并对齐良好且相邻的块以形成更长的近似逐字块,然后过滤这些块以仅保留那些超过指定最小长度的块,以便每个保留的块足够长以支持提取声明。下面,我们描述每个步骤(识别、合并和过滤),我们如何在实践中组合它们,以及我们如何使用生成的近似逐字块来报告有关提取的不同信息。

图 4:近乎逐字复制的块形成。在识别出逐字复制块后,我们将紧密对齐的邻近块合并(公式 4)。在两个子图中,块都是对齐的( )。第一次合并(M1)非常严格,最大间隙为 个词,然后过滤器 1(F1)只保留长度至少为 个词的块( )。第二次合并(M2)在 F1 保留的块上执行,稍微宽松一些( ),因此第二次过滤器更严格( )。在图 4(a)中,M1 合并了非常邻近的块。剩下的块——块 1、块 2*(=块 2+块 3+块 4+块 5)和块 6——每个都足够长,可以被 F1 保留(但请注意,此时它们不会被 F2 保留)。这些块在 M2 中被合并,形成了一个 个词的块,该块在 F2 后保留。在图 4(b)中,没有块被保留。识别步骤返回了一些逐字匹配的块,但它们太短,不能作为有效的提取证据。我们的两步合并和过滤程序去除了它们;它们不计入我们的提取指标, (公式 6)。更多详情请参见附录 B。

Identify verbatim blocks.

Given two lightly normalized texts (the reference book) and (the generated text), we split each on whitespace characters to obtain ordered lists of words

.

We then find verbatim matching blocks by greedily locating the longest substring of words shared by and , and recursively repeating the search on the unmatched regions to the left and right (difflib SequenceMatcher, 2025).

This produces an ordered set of verbatim-matching blocks

识别逐字块。给定两个轻度规范化的文本 (参考书)和 (生成的文本),我们将每个文本按空白字符分割,得到有序的单词列表 。然后通过贪婪地定位 和 共享的最长单词子串来找到逐字匹配块,并对左侧和右侧的不匹配区域递归地重复搜索(difflib SequenceMatcher,2025)。这产生了一个有序的逐字匹配块集合。

| (3) |

where block is defined by:

(i) a starting index in ,

(ii) a starting index in , and

(iii) a length , measured in words.

Each block satisfies

exactly, and has equal verbatim length in both and . (Figure 4).

Each region of the reference book text can be included in at most one block.

Therefore, starting with this identification procedure means that we capture unique instances of extraction;

we do not count repeated extraction of the same passage if it appears in the generated text multiple times.

Further, this greedy matching procedure induces a monotone alignment between and , so the resulting blocks are ordered consistently in both texts.

As a result, verbatim-matching text that appears out-of-order in with respect to may not be matched to a block—i.e., may be missed by this identification procedure.

We only merge adjacent blocks and filtering preserves block order, so monotonicity (and thus consistent block ordering) is maintained throughout all merge and filter steps.

块 的定义如下:(i) 在 中的起始索引 ,(ii) 在 中的起始索引 ,以及 (iii) 以词为单位的长度 。每个块 满足 ,并且在 和 中具有相同的逐字长度 (图 4)。参考书文本的每个区域最多只能包含在一个块中。因此,从这种识别过程开始意味着我们捕获了提取的唯一实例;如果同一段落多次出现在生成文本中,我们不会重复计算其提取。此外,这种贪婪匹配过程在 和 之间引入了单调对齐,因此生成的块在两种文本中都是有序的。结果,相对于 在 中顺序错乱的逐字匹配文本可能无法匹配到某个块——即可能被这种识别过程遗漏。我们仅合并相邻的块,且过滤操作保留了块的顺序,因此单调性(以及由此产生的块的一致性排序)在整个合并和过滤步骤中都得以保持。

Merge blocks.

Let and be consecutive blocks in an ordered set .

We define the inter-block gaps

,

which measure the number of unmatched words between the two blocks in and , respectively.

We merge blocks and if the following conditions hold:

合并块。设 和 是有序集合 中的连续块。我们定义块间间隙 ,分别测量 和 中两个块之间未匹配单词的数量。如果满足以下条件,我们将合并块 和 :

| (4) |

Here, specifies the maximum number of unmatched words allowed between consecutive blocks, and limits merges to blocks that occur in roughly corresponding locations in the reference and generated texts, which helps avoid stitching together unrelated content.

When these conditions are met, we replace blocks and with a single merged near-verbatim block with effective matched length

,

and spanning indices

and

(Figure 4).

We conservatively do not count gaps reconciled by a merge:

counts only verbatim-matched words, so it is less than the length of in , which spans the gap between and (and similarly less than in ).

其中, 指定允许在连续块之间存在的最大未匹配单词数, 限制合并为在参考文本和生成文本中大致对应位置的块,这有助于避免将不相关内容拼接在一起。当满足这些条件时,我们用单个合并的近乎逐字块替换块 和 ,其有效匹配长度为 ,跨越索引 和 (图 4)。我们保守地不计入合并解决的间隙: 仅计算逐字匹配的单词,因此它小于 在 中的长度,后者跨越了 和 之间的间隙(同样小于 在 中的长度)。

Filter blocks. Very short matching blocks may reflect coincidental overlap rather than meaningful long-form similarity that we can safely call extraction (Figure 4(b)).

We therefore filter blocks by a minimum length threshold .

Given an ordered block set , we define the filtered ordered block set

过滤块。非常短的匹配块可能反映偶然的重叠,而不是我们能够安全地称为提取的具有意义的长格式相似性(图 4(b))。因此,我们通过最小长度阈值 过滤块。给定一个有序块集 ,我们定义过滤后的有序块集

| (5) |

In practice, after identifying verbatim blocks, we perform two merge-and-filter passes (Algorithm 1) to obtain near-verbatim blocks that reflect extracted training data.

In the first pass, we merge blocks separated by trivial gaps

( and , see Figure 4), and then filter out short blocks by retaining only those with length at least .444This is conservative; words is approximately half of the words typically used in discoverable extraction.

See Appendix B.

这是保守的; 个词大约是通常用于可发现提取的 个词的一半。参见附录 B。

在实践中,在识别出逐字块后,我们执行两次合并和过滤过程(算法 1),以获得反映提取训练数据的近似逐字块。在第一遍中,我们合并由微小间隙( 和 ,见图 4)分隔的块,然后通过仅保留长度至少为 的块来过滤掉短块。 4

In the second pass, we perform a more relaxed but still stringent merge to consolidate passage-level matches (, ), followed by a final filter that retains only sufficiently long near-verbatim blocks () to support a valid extraction claim (Section 3.3.2).

Because filtering is interleaved with merging, some fragmented near-verbatim passages may fail to consolidate into a single long block and may be filtered out.

This is a deliberate trade-off:

we prefer to be conservative and incur false negatives (i.e., miss some instances of extraction) rather than risk including false positives.

在第二次遍历时,我们执行更宽松但仍严格的合并操作,以整合段落级别的匹配( , ),随后进行最终过滤,仅保留足够长的逐字块( )以支持有效的提取声明(第 3.3.2 节)。由于过滤与合并交替进行,一些片段化的逐字段落可能无法合并成一个长块,并可能被过滤掉。这是一个有意做出的权衡:我们宁愿保守一些并承担假阴性(即漏掉一些提取实例),而不是冒险包含假阳性。

Metrics from near-verbatim blocks.

From the near-verbatim, extracted text represented in the final ordered block set, we can aggregate several useful metrics. Let denote the final set of blocks returned by the two-pass merge-and-filter procedure (Algorithm 1).

We define

逐字块指标。从最终有序块集中表示的逐字提取文本,我们可以汇总几个有用的指标。设 表示两遍合并和过滤过程(算法 1)返回的最终块集。我们定义

| (6) |

which is the total number of in-order words extracted near-verbatim

in with respect to .

From , we then define the relative near-verbatim recall of book extracted in generation :

这是相对于 在 中按顺序逐字提取的总词数。然后,我们从 定义在生成 中提取的书籍 的相对逐字召回率:

| (7) |

which reflects the proportion of in-order, near-verbatim extracted text relative to the length of the whole book.

We typically report as a percentage rather than a fraction (e.g., Figure 1).

For further analysis, we also define in absolute word counts how much in-order, near-verbatim text we failed to extract in (i.e., is missing in ) and how much additional non-book text is in (i.e., is not contained near-verbatim in ):

这反映了按顺序、近乎逐字提取的文本占整本书长度的比例。我们通常以百分比而非分数的形式报告 (例如,图 1)。为了进一步分析,我们还定义了绝对词数,即我们在 中未能按顺序、近乎逐字提取的文本量(即 中缺失的文本)以及 中额外的非书文本量(即未近乎逐字包含在 中的文本):

| (8) |

Since counts only aligned, near-verbatim blocks from an ordered set, verbatim text that is reproduced out-of-order may be present in but excluded from .

Such text would instead be counted in and , even though it represents valid extraction, and so our measurements may under-count extraction.555To identify these cases, as well as instances of duplicated extraction in , one could iteratively re-run our measurement procedure on and unmatched (non-block) text in .

为了识别这些情况,以及 中重复提取的实例,可以在 和 中未匹配(非块)文本上迭代重新运行我们的测量程序。

由于 仅统计有序集中对齐的、近乎逐字复制的文本块,因此顺序错乱的逐字复制的文本可能存在于 中但被排除在 之外。此类文本会被计入 和 ,尽管它代表有效的提取,因此我们的测量可能低估了提取量。 5

3.3.2 Claiming extraction success without information about training-data membership

3.3.2 在没有关于训练数据成员资格信息的情况下声称提取成功

We next elaborate on why, absent certain knowledge of production LLM training datasets, the above measurement procedure captures valid evidence of extraction.

When making a claim about extraction of a sequence of training data, one is necessarily also making a claim that this sequence was in the training dataset (Carlini et al., 2021).

By definition, “it is only possible to extract memorized training data, and (tautologically) training data can only be memorized if they are included—i.e., are members—of the training dataset.

To demonstrate extraction is therefore to demonstrate memorization, and memorization implies membership” in the training dataset (Cooper et al., 2025).

我们接下来阐述,为何在没有关于生产 LLM 训练数据集的某些知识的情况下,上述测量程序能够捕捉到有效的提取证据。当关于训练数据序列的提取做出断言时,必然也在断言该序列包含在训练数据集中(Carlini 等人,2021)。根据定义,“只有能够提取记忆中的训练数据,并且(同义反复地)训练数据只有包含在训练数据集中——即作为训练数据集的成员——才能被记忆。因此,证明提取就是证明记忆,而记忆意味着它是训练数据集的成员”(Cooper 等人,2025)。

Much prior work on extraction is conducted on open-weight models with known training datasets (Lee et al. (2022); Carlini et al. (2023); Hayes et al. (2025b); Wei et al. (2025); Section 3.2);

it is known with certainty that the extracted data were members of the training dataset.

In contrast, in our production LLM setting, we do not have access to certain, ground-truth information about the training dataset.

This means that, embedded in our claims for extraction of books text, we are also claiming that the text that we generated was included near-verbatim in production LLMs’ training data.666We only make membership and memorization claims about this specific text, not the whole book (except for the four whole extracted books for Claude 3.7 Sonnet).

For more on this distinction, see Appendix E.6, Cooper et al. (2025).

我们仅就这段特定文本提出成员资格和记忆主张,而不是整本书(除了为 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 提取的四本完整书籍)。关于这一区别的更多内容,参见附录 E.6,Cooper 等人(2025)。

以往关于提取的研究大多是在开放权重模型上进行的,这些模型的训练数据集是已知的(Lee 等人(2022 年);Carlini 等人(2023 年);Hayes 等人(2025b 年);Wei 等人(2025 年);第 3.2 节);可以确定的是,提取的数据都是训练数据集中的成员。相比之下,在我们的生产 LLM 环境中,我们没有访问关于训练数据集的某些、真实信息。这意味着,在我们关于提取书籍文本的主张中,我们也声称我们生成的文本几乎逐字地包含在生产 LLM 的训练数据中。

As noted at the beginning of this section, to make a valid claim, the generated text has to be sufficiently long and similar to the suspected training data, such that memorization of that data from the training set is the overwhelmingly plausible explanation.

This is because, when a sufficiently long, unique sequence of training data is generated, “[t]he probability that this would have happened by random chance is astronomically low, and so we can say that the model has ‘memorized’ this training data” (Carlini, 2025);

that sequence of training data “must be stored somewhere in the model weights” (Nasr et al., 2023).

如本节开头所述,要提出有效主张,生成的文本必须足够长且与可疑的训练数据相似,以至于从训练集中记忆这些数据是极有可能的解释。这是因为,当生成足够长且独特的训练数据序列时,“这种结果通过随机偶然发生的概率极低,因此我们可以认为模型‘记忆’了这些训练数据”(Carlini,2025);该训练数据序列“必须以某种方式存储在模型权重中”(Nasr 等人,2023)。

In their prior work on extraction from production LLMs, Nasr et al. (2023) ensure validity by requiring that the LLM produce sufficiently long (-token/roughly -word) sequences that exactly match a proxy dataset reflecting data likely used for LLM pre-training (Nasr et al., 2023; 2025).

While tokens may seem relatively short, for an LLM, exact matches of this length are extraordinarily unlikely without memorization.777The prompts that elicited these training data sequences did not contain these sequences’ prefixes;

they involved completely unrelated jailbreak prompts, which queried ChatGPT 3.5 to repeat a single token (e.g., “poem”) forever.

引发这些训练数据序列的提示不包含这些序列的前缀;它们涉及完全无关的越狱提示,这些提示查询 ChatGPT 3.5 重复单个标记(例如,“poem”)无限次。

在他们之前关于从生产 LLMs 中提取的工作中,Nasr 等人(2023 年)通过要求 LLMs 生成足够长( -token/大约 -词)的序列,这些序列与一个反映可能用于 LLMs 预训练的数据的代理数据集完全匹配,来确保有效性(Nasr 等人,2023 年;2025 年)。虽然 tokens 可能看起来相对较短,但对于一个 LLM 来说,如果没有记忆,这种长度的精确匹配是极不可能的。 7

Therefore, the results in Nasr et al. (2023) are accepted as strong evidence for extraction, without direct knowledge of the training dataset.

In our experiments, we target extraction of specific documents, which we know are widely available in several common pre-training datasets, including Books3 (where we access our reference texts) and other torrents like LibGen (Appendix C.1).

Beyond the initial short seed prefix, we provide no other book-specific information to the LLM.

We also set a much higher bar than generating words to call extraction successful:

at a minimum, we require -word near-exact passages, and often retrieve passages that are significantly longer—e.g., thousands of words (Table 1, Section 4.2).

Together, the relatively short length of the prefix in Phase 1, the lack of book-specific guidance in the continuation loop in Phase 2, and the length and fidelity of the near-verbatim matches we identify are strong evidence of memorization of training data, which we have successfully extracted in outputs.

因此,Nasr 等人(2023)的研究结果被视为强有力的证据,证明了在不直接了解训练数据集的情况下进行提取。在我们的实验中,我们针对特定文档的提取,这些文档我们知道在多个常见的预训练数据集中广泛存在,包括 Books3(我们在其中获取参考文本)以及其他如 LibGen 的种子文件(附录 C.1)。除了初始的短种子前缀外,我们未向 LLM 提供任何其他与书籍相关的信息。我们还设定了比生成 个单词更高的标准来判定提取成功:至少要求 个单词的近似精确段落,并且经常检索到显著更长的段落——例如数千个单词(表 1,第 4.2 节)。综合来看,第一阶段中前缀的相对较短长度、第二阶段延续循环中缺乏与书籍相关的指导,以及我们识别出的近似逐字匹配的长度和保真度,都是训练数据记忆的强有力证据,我们已成功在输出中提取这些数据。

4 Experiments 4 实验

We now present our main results.

We begin with details about the exact production LLMs and books we test, as well as high-level variations in how we instantiate our two-phase procedure (Section 4.1).

We then give a summary of high-level, experimental outcomes for different books and LLMs (Section 4.2), before discussing more detailed LLM-specific results (Section 4.3).

Additional results can be found in Appendix D.

现在我们展示我们的主要结果。我们首先提供关于我们测试的精确生产 LLM 和书籍的详细信息,以及我们如何实例化我们两阶段程序的总体变化(第 4.1 节)。然后,我们给出针对不同书籍和 LLM 的实验结果的总结(第 4.2 节),接着讨论更详细的针对特定 LLM 的结果(第 4.3 节)。更多结果可以在附录 D 中找到。

4.1 Setup 4.1 设置

Given that production systems change over time (i.e., are unstable compared to open-weight LLMs), we limited our experiments to between mid-August and mid-September 2025.

We attempt to extract thirteen books from four production LLMs, and predominantly report results for the single run that shows the maximum amount of extraction we observed for a given production LLM, book, and generation configuration.

考虑到生产系统会随时间变化(即与开放权重 LLM 相比是不稳定的),我们将实验限制在 2025 年 8 月中旬至 9 月中旬之间。我们尝试从四个生产 LLM 中提取十三本书籍,并且主要报告针对给定生产 LLM、书籍和生成配置中我们观察到的最大提取量的单次运行结果。

Production LLMs.

The four production LLMs we evaluate are

Claude 3.7 Sonnet (claude-3-7-sonnet-20250219), GPT-4.1 (gpt-4.1-2025-04-14), Gemini 2.5 Pro (gemini-2.5-pro), and Grok 3 (grok-3).

Throughout, we refer to these LLMs by their names, rather than these API versions.

Claude 3.7 Sonnet has a knowledge cutoff date of October 2024 Anthropic (2025),

GPT-4.1’s is June 2024 (OpenAI, 2025),

Grok 3’s is November 2024 (xAI, 2025), and Gemini 2.5 Pro’s is January 2025 (Google Cloud, 2025).

生产 LLMs。我们评估的四个生产 LLMs 是 Claude 3.7 Sonnet(claude-3-7-sonnet-20250219)、GPT-4.1(gpt-4.1-2025-04-14)、Gemini 2.5 Pro(gemini-2.5-pro)和 Grok 3(grok-3)。在整个过程中,我们使用这些 LLMs 的名称来指代它们,而不是这些 API 版本。Claude 3.7 Sonnet 的知识截止日期是 2024 年 10 月 Anthropic(2025 年),GPT-4.1 的知识截止日期是 2024 年 6 月(OpenAI,2025 年),Grok 3 的知识截止日期是 2024 年 11 月(xAI,2025 年),Gemini 2.5 Pro 的知识截止日期是 2025 年 1 月(Google Cloud,2025 年)。

图 5:提取书籍的比例( )。我们展示了针对运行了第二阶段的十二本书的 (%)。每个条形图都标注了相应的 生产 LLM-书籍对;括号中的数字是第一阶段( 对于 Gemini 2.5 Pro 和 Grok 3,因为我们没有越狱这些生产 LLM)中的 BoN 样本 。 表示第一阶段失败; 表示我们没有尝试第二阶段。灰色阴影表示公共领域书籍。每行的垂直轴有不同的刻度。注意:每个条形图反映了第二阶段的一次运行,其中每个 LLM 的基础生成配置是固定的,但在不同 LLM 之间变化。这些条形图组并不反映在相同条件下测试所有生产 LLM 获得的结果的比较。

Books. We attempt to extract thirteen books: eleven in-copyright in the U.S. and two in the public domain.

We predominantly selected books that Cooper et al. (2025) observe to be highly memorized by Llama 3.1 70B (Appendix C.1).

The books under copyright in the U.S. are Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (Rowling, 1998) (which we sometimes abbreviate in plot labels as “Harry Potter 1”), Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (Rowling, 2000) (“Harry Potter 4”), 1984 (Orwell, 1949), The Hobbit (Tolkien, 1937), The Catcher in the Rye (Salinger, 1951), A Game of Thrones (Martin, 1996), Beloved (Morrison, 1987), The Da Vinci Code (Brown, 2003), The Hunger Games (Collins, 2008),

Catch-22 (Heller, 1961), and The Duchess War (Milan, 2012).

The public domain books are Frankenstein (Shelley, 1818) and The Great Gatsby (Fitzgerald, 1925).

We obtained these books from the Books3 corpus, which was torrented and released in 2020.888We have a copy of this dataset for research purposes only, stored on a university research computing cluster.

我们仅保留了一份该数据集用于研究目的,存储在大学科研计算集群上。

书籍。我们尝试提取十三本书:其中十一本在美国受版权保护,两本已进入公共领域。我们主要选择了 Cooper 等人(2025 年)观察到 Llama 3.1 70B 高度记忆的书籍(附录 C.1)。美国受版权保护的书籍包括《哈利·波特与魔法石》(罗琳,1998 年)(我们在情节标签中有时将其缩写为“哈利·波特 1”)、《哈利·波特与火焰杯》(罗琳,2000 年)(“哈利·波特 4”)、《1984》(奥威尔,1949 年)、《霍比特人》(托尔金,1937 年)、《麦田里的守望者》(塞林格,1951 年)、《冰与火之歌》(马丁,1996 年)、《宠儿》(莫里森,1987 年)、《达·芬奇密码》(布朗,2003 年)、《饥饿游戏》(柯林斯,2008 年)、《第二十二条军规》(赫尔勒,1961 年)和《公爵夫人战争》(米兰,2012 年)。公共领域的书籍包括《弗兰肯斯坦》(雪莱,1818 年)和《了不起的盖茨比》(菲茨杰拉德,1925 年)。我们从 Books3 语料库获取了这些书籍,该语料库于 2020 年通过 BT 下载发布。 8

Therefore, all of these books significantly pre-date the knowledge cutoffs of every LLM we test.

Following Cooper et al. (2025), as a negative control we also test The Society of Unknowable Objects (Brown, 2025), published in digital formats on July 31, 2025.

This date is long after the training cutoffs for all four LLMs, and therefore it is very unlikely that this original novel contains text that is in the training data.

因此,所有这些书都显著早于我们测试的每一个 LLM 的知识截止日期。根据 Cooper 等人(2025 年)的研究,我们作为负对照也测试了《不可知之物社》(Brown,2025 年),该书于 2025 年 7 月 31 日以数字格式出版。这个日期远在所有四个 LLM 的训练截止日期之后,因此该原创小说包含的训练数据中的文本的可能性非常小。

Configurations for the two-phase procedure and quantifying extraction success.

For Phase 1 (Section 3.1), we set a maximum BoN budget of for each experiment.

In our initial experiments, we observed that we did not need to jailbreak Gemini 2.5 Pro or Grok 3 ().

For the initial prompt of the instruction and seed prefix, we generate up to tokens as the response.

We only attempt Phase 2 if Phase 1 succeeds, with the production LLM producing a response that is at least a loose approximation of the target suffix, i.e., (Equation 2). We run the Phase 2 continuation loop (Section 3.2) for up to a maximum query budget, or until the production LLM responds with a refusal or stop phrase, e.g., “THE END”.

The four production-LLMs APIs expose different, configurable generation parameters (e.g., frequency penalty).

For all four LLMs, we set temperature to , but other LLM-specific configurations vary (Appendix C.2).

For instance, based on our exploratory initial experiments, we observed it was necessary to set the per-interaction maximum generation length differently for each LLM to evade output filters.

For our extraction measurements (Algorithm 1), we use the same conservative configurations across all runs.

For the first merge-and-filter, we set

, , and

;

for the second,

, , and (Section 3.3.1 & Appendix B).

We provide full details on experimental configurations in Appendix C.

两阶段流程的配置和量化提取成功率。对于第一阶段(第 3.1 节),我们为每个实验设置最大 BoN 预算为 。在我们的初始实验中,我们观察到我们不需要破解 Gemini 2.5 Pro 或 Grok 3( )。对于指令和种子前缀的初始提示,我们生成最多 个 token 作为响应。我们仅在第一阶段成功时尝试第二阶段,即生产 LLM 生成至少是目标后缀的松散近似响应,即 (公式 2)。我们运行第二阶段延续循环(第 3.2 节),直到达到最大查询预算或生产 LLM 响应拒绝或停止短语,例如“THE END”。四个生产 LLM API 暴露不同的、可配置的生成参数(例如,频率惩罚)。对于所有四个 LLM,我们设置温度为 ,但其他 LLM 特定配置有所不同(附录 C.2)。例如,根据我们的探索性初始实验,我们观察到需要为每个 LLM 设置不同的每交互最大生成长度以规避输出过滤器。 在我们的提取测量(算法 1)中,所有运行都使用相同的保守配置。对于第一次合并和过滤,我们设置 、 和 ;对于第二次,设置 、 和 (第 3.3.1 节 & 附录 B)。我们在附录 C 中提供了实验配置的详细信息。

4.2 High-level extraction outcomes

4.2 高层级提取结果

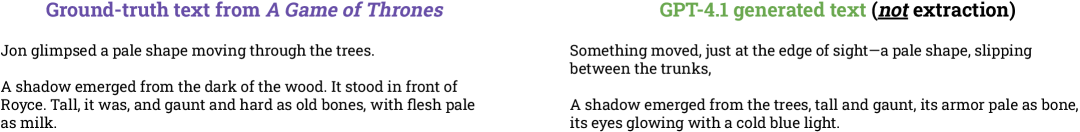

Across all Phase 2 runs, we extract hundreds of thousands of words of text.

We provide two concrete examples of extracted text from in-copyright books in Figure 6, but do not redistribute long-form generations of in-copyright material.

We share lightly normalized diffs for Claude 3.7 Sonnet on Frankenstein and The Great Gatsby, which are books in the public domain.

We do not include The Duchess War in plots;

of the thirteen books we attempt to extract, this is the only book where Phase 1 failed for all four production LLMs.

Similarly, we omit results for our negative control, The Society of Unknowable Objects;

as expected, Phase 1 also failed for this book (Appendix D.1).

在所有第二阶段运行中,我们提取了数十万字的文本。我们在图 6 中提供了两个来自版权保护书籍的提取文本实例,但不会重新分发版权保护材料的长期生成内容。我们分享了 Claude 3.7 Sonnet on Frankenstein 和 The Great Gatsby 的轻微规范化差异,这两本书都在公共领域。我们不包含 The Duchess War 在图中;在我们试图提取的十三本书中,这是唯一一本所有四个生产 LLMs 在第一阶段都失败的书。类似地,我们省略了我们负控制组 The Society of Unknowable Objects 的结果;正如预期的那样,这本书在第一阶段也失败了(附录 D.1)。

Interpreting our bar plots.

In this section, each bar reflects results from a single, specifically configured run for a given production LLM and book;

across bars, the underlying generation configurations vary.

As a result, our results should be interpreted only as describing specific experimental outcomes:

each bar in a plot conveys how much extraction we observed under the specified experimental settings;

since these settings are not fixed across bars, our plots do not make evaluative claims about relative extraction risk across production LLMs.

(See Chouldechova et al. (2025), and further discussion in Sections 1 and 5.1.)

解读我们的条形图。在本节中,每个条形图反映了一个特定配置的生产 LLM 和书籍的单一运行结果;不同条形图之间,底层的生成配置有所不同。因此,我们的结果应仅被理解为描述特定的实验结果:每个条形图传达了在指定实验设置下观察到的提取量;由于这些设置在不同条形图中并非固定不变,我们的条形图并未对生产 LLM 之间的相对提取风险做出评估性声明。(参见 Chouldechova 等人(2025 年)的研究,并在第 1 节和第 5.1 节中进一步讨论。)

(a) Gemini 2.5 Pro, 《霍比特人》

(b) Grok 3, 《麦田里的守望者》

图 6:从版权受保护的书籍中提取的文本。我们提供了两个在第二阶段提取文本的裁剪示例,将 Books3 中的真实书籍与生产 LLM 的生成文本进行对比。黑色文本反映了两者之间的逐字匹配;粗体蓝色文本反映了书中未出现的生成文本;删除线红色文本表示真实文本在生成文本中缺失。

| Book 书 | Claude 3.7 Sonnet | GPT-4.1 | Gemini 2.5 Pro | Grok 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Cont. # 继续 | Cost 成本 | # Cont. # 继续 | Cost 成本 | # Cont. # 继续 | Cost 成本 | # Cont. # 继续 | Cost 成本 | |||||

| Harry Potter 1 哈利·波特 1 | 480 | $119.97 | 6658 | 31 | $1.37 | 821 | 171 | $2.44 | 9070 | 52 | $8.16 | 6337 |

| Frankenstein 弗兰肯斯坦 | 374 | $55.41 | 8732 | 33 | $0.19 | 474 | 204 | $0.38 | 448 | 300 | $77.12 | 275 |

| The Hobbit 霍比特人 | 1000 | $134.87 | 8835 | 4 | $0.16 | 205 | 188 | $0.52 | 571 | 115 | $23.40 | 1816 |

| A Game of Thrones 冰与火之歌 | 562 | $124.49 | 1091 | 15 | $0.16 | 0 | 166 | $0.36 | 138 | 195 | $42.36 | 836 |

表 1:第 2 阶段的继续查询次数、成本和最大块长度。对于图 7 中的每本书,我们展示了在第 2 阶段查询每个生产 LLM 以继续的次数,以及运行此循环的成本(美元)。我们还展示了第 2 阶段产生的最长近乎逐字复制的块( )的长度。参见附录 D.2。

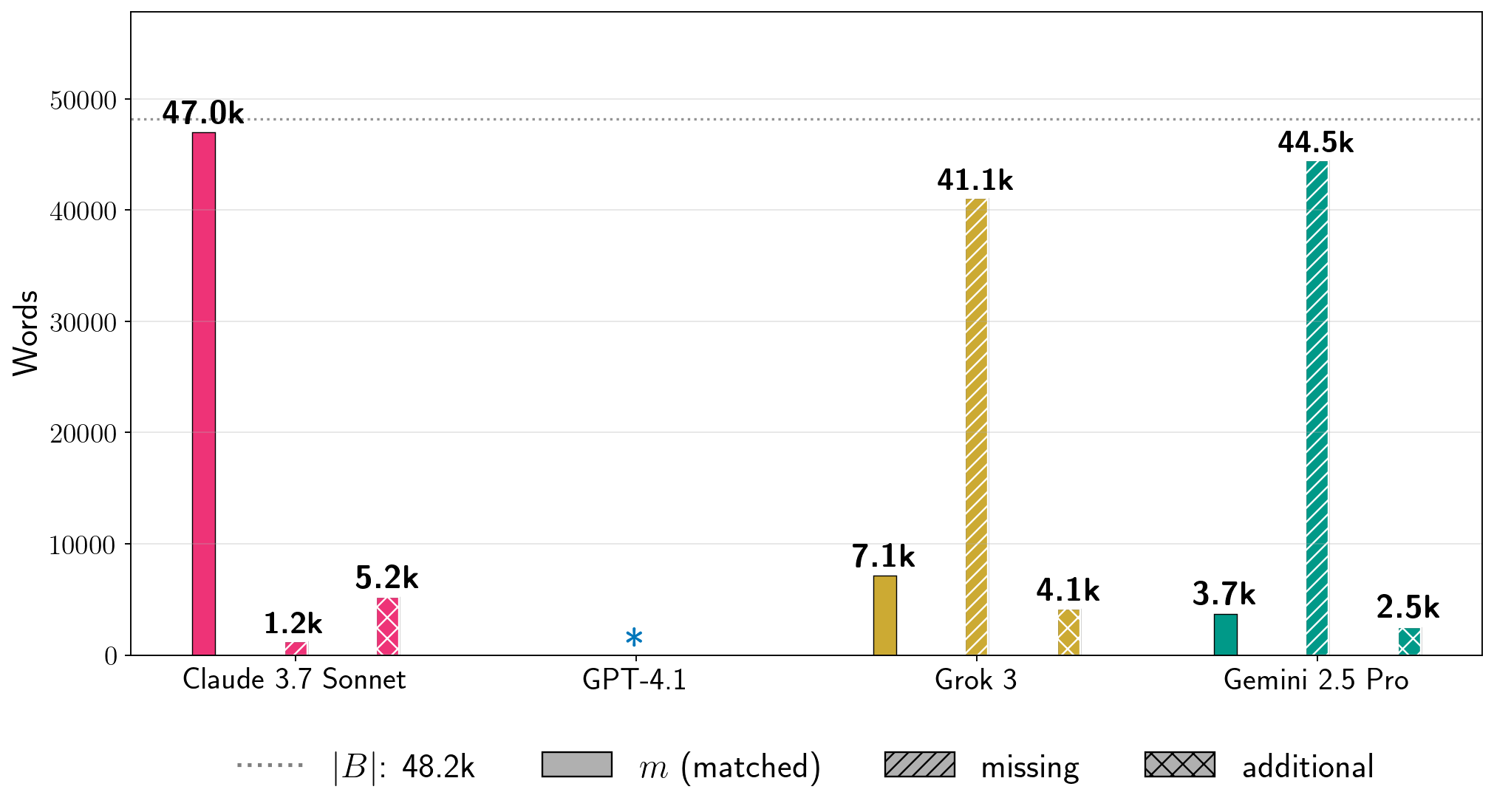

Proportion of book extracted ().

Figure 5 plots (Equation 7):

the overall proportion of a book extracted in in-order, near-verbatim blocks (Section 3.3.1).

For a given production LLM, we fix the same generation configuration across books;

however, the generation configuration varies across LLMs.

Overall, these results show that it is possible to extract text across books and frontier LLMs.

Importantly, we did not jailbreak Gemini 2.5 Pro and Grok 3 in Phase 1 to obtain these results in Phase 2.

For Claude 3.7 Sonnet and GPT-4.1, we use BoN with up to attempts in Phase 1.

While in terms of dollar-cost BoN is cheap to run for this budget, we note that it almost always required significantly larger —often —to jailbreak GPT-4.1

compared to Claude 3.7 Sonnet.

In four cases, Claude 3.7 Sonnet’s generations recover over of the corresponding reference book.

Two of these books—Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and 1984—are in-copyright in the U.S., while the other two—The Great Gatsby and Frankenstein—are in the public domain.

In three other cases for Claude 3.7 Sonnet, .

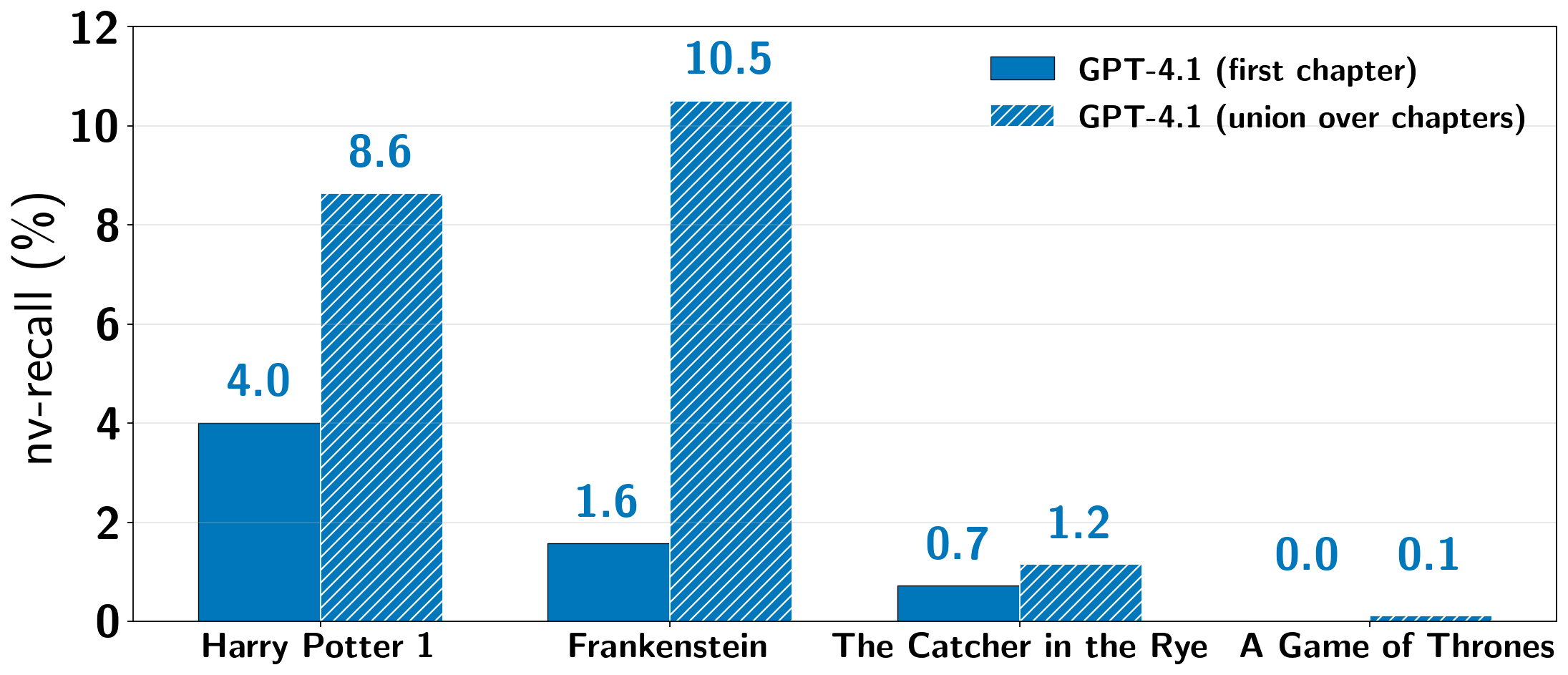

With respect to LLM-specific generation configurations, we extract significant amounts of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and other books from all four production LLMs.

提取书籍的比例( )。图 5 绘制了 (公式 7):按顺序、近乎逐字提取的书籍整体比例(第 3.3.1 节)。对于给定的生产 LLM,我们在不同书籍中保持相同的生成配置;然而,生成配置在不同 LLM 之间有所不同。总体而言,这些结果表明可以在不同书籍和前沿 LLM 之间提取文本。重要的是,我们在第一阶段没有越狱 Gemini 2.5 Pro 和 Grok 3 以在第二阶段获得这些结果。对于 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 和 GPT-4.1,我们在第一阶段使用 BoN,最多尝试 次。虽然从美元成本来看,BoN 在这个预算下运行很便宜,但我们注意到,与 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 相比,越狱 GPT-4.1 几乎总是需要显著更大的 ——通常是 。在四个案例中,Claude 3.7 Sonnet 的生成恢复了对应参考书籍的 以上。其中这两本书——《哈利·波特与魔法石》和《1984》——在美国受版权保护,而另外两本——《了不起的盖茨比》和《弗兰肯斯坦》——则属于公共领域。在 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 的另外三个案例中, 。 关于特定于 LLM 的生成配置,我们从全部四个生产 LLM 中提取了大量《哈利·波特与魔法石》和其他书籍的内容。

We frequently query the production LLM to continue hundreds of times per Phase 2 run, without encountering guardrails.

However, when we run Phase 2 for GPT-4.1, we hit a refusal fairly early on in the continuation loop.

For instance, for Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, this happens at the end of the first chapter.

Therefore, while we report with respect to the full book, near-verbatim extraction is limited to the first chapter for GPT-4.1.

For the other three production LLMs, we almost always do not encounter refusals (Section 4.3), and so halt Phase 2 when either a maximum query budget is expended, the LLM returns a response containing a stop phrase (e.g., “THE END”), or the API returns an HTTP error. (Section 3.2).

在 Phase 2 的每个运行中,我们频繁地向生产 LLM 查询数百次,并未遇到任何限制措施。然而,在为 GPT-4.1 运行 Phase 2 时,我们在延续循环的早期就遇到了拒绝。例如,对于《哈利·波特与魔法石》,这发生在第一章的结尾。因此,虽然我们针对整本书报告 ,但针对 GPT-4.1 的近乎逐字提取仅限于第一章。对于其他三个生产 LLM,我们几乎从不遇到拒绝(第 4.3 节),因此当达到最大查询预算、LLM 返回包含停止短语的响应(例如,“THE END”)或 API 返回 HTTP 错误时,我们会停止 Phase 2(第 3.2 节)。

The cost of the loop varies across runs, according to the provider’s billing policy, the number of queries, and the number of tokens returned per query.

For instance, as shown in Table 1, it cost approximately $119.97 to extract Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone with from jailbroken Claude 3.7 Sonnet and $1.37 for jailbroken GPT-4.1 ();

it cost approximately $2.44 for not-jailbroken Gemini 2.5 Pro () and $8.16 for not-jailbroken Grok 3 ().

循环的成本因运行而异,根据提供商的计费政策、查询次数以及每个查询返回的 token 数量而变化。例如,如表 1 所示,使用被破解的 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 从 中提取《哈利·波特与魔法石》的成本约为 119.97 美元,而使用被破解的 GPT-4.1 的成本为 1.37 美元( );使用未破解的 Gemini 2.5 Pro 的成本约为 2.44 美元( ),而使用未破解的 Grok 3 的成本为 8.16 美元( )。

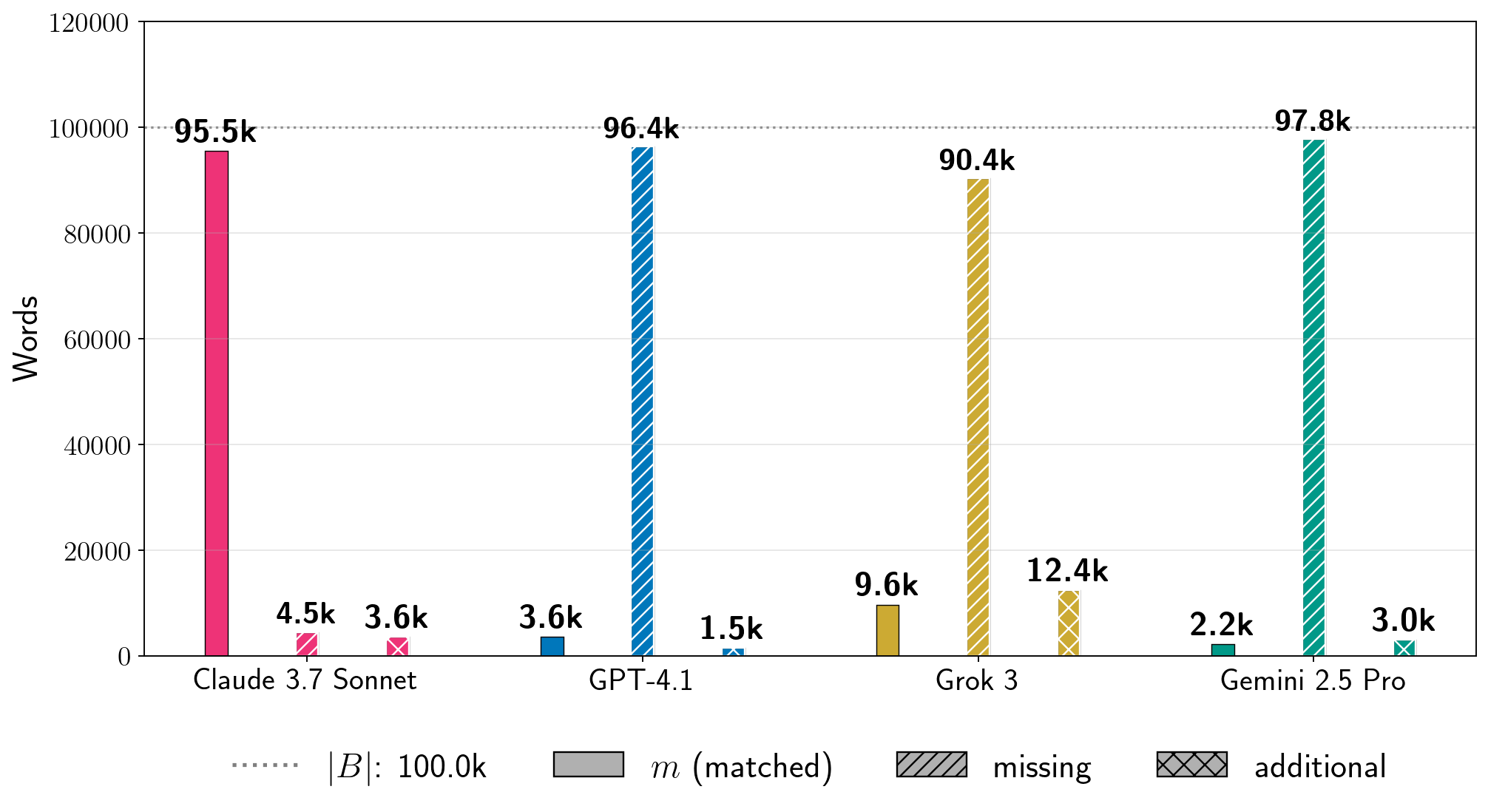

(a) 《哈利·波特与魔法石》

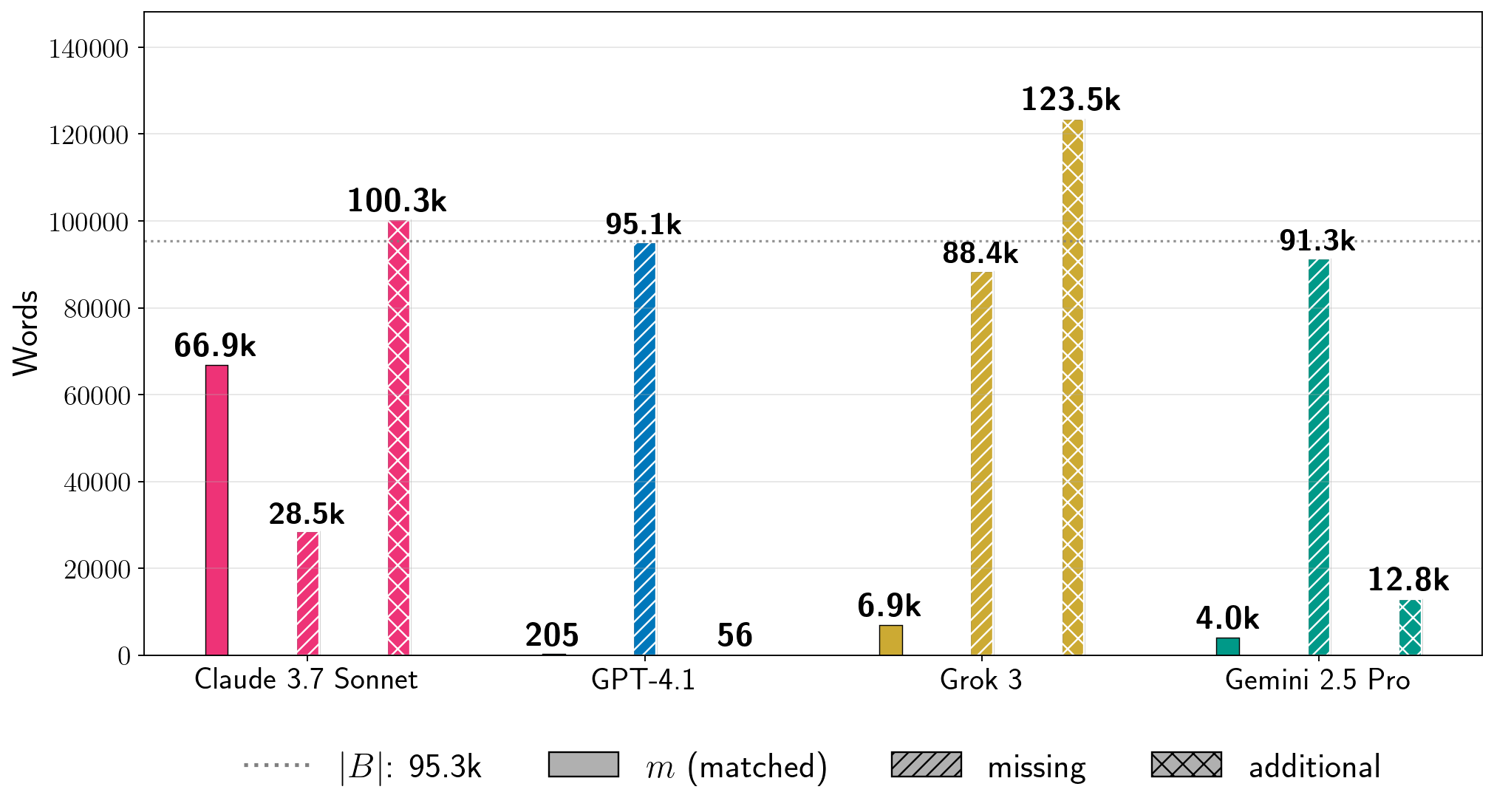

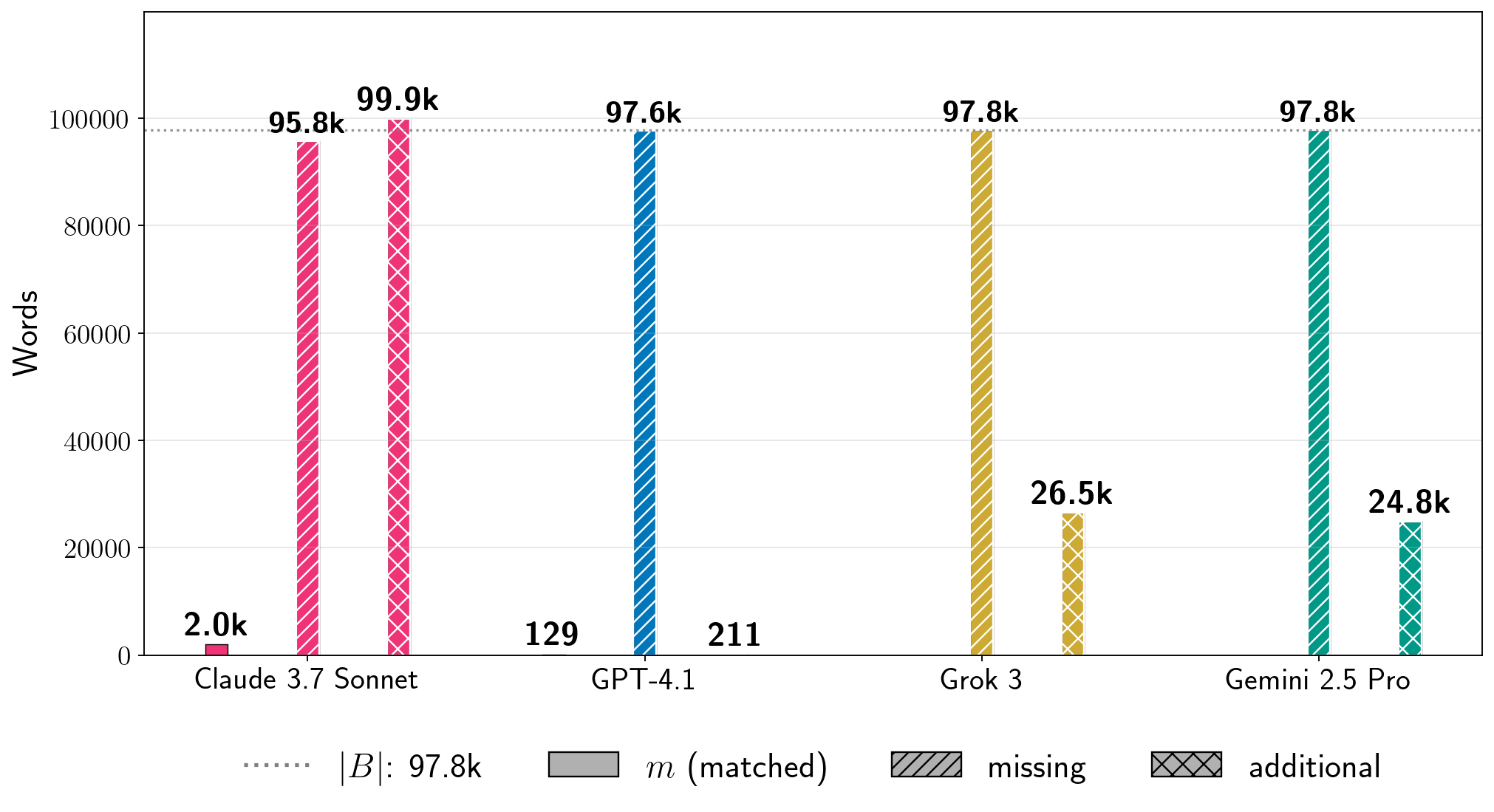

(b) 弗兰肯斯坦(公共领域)

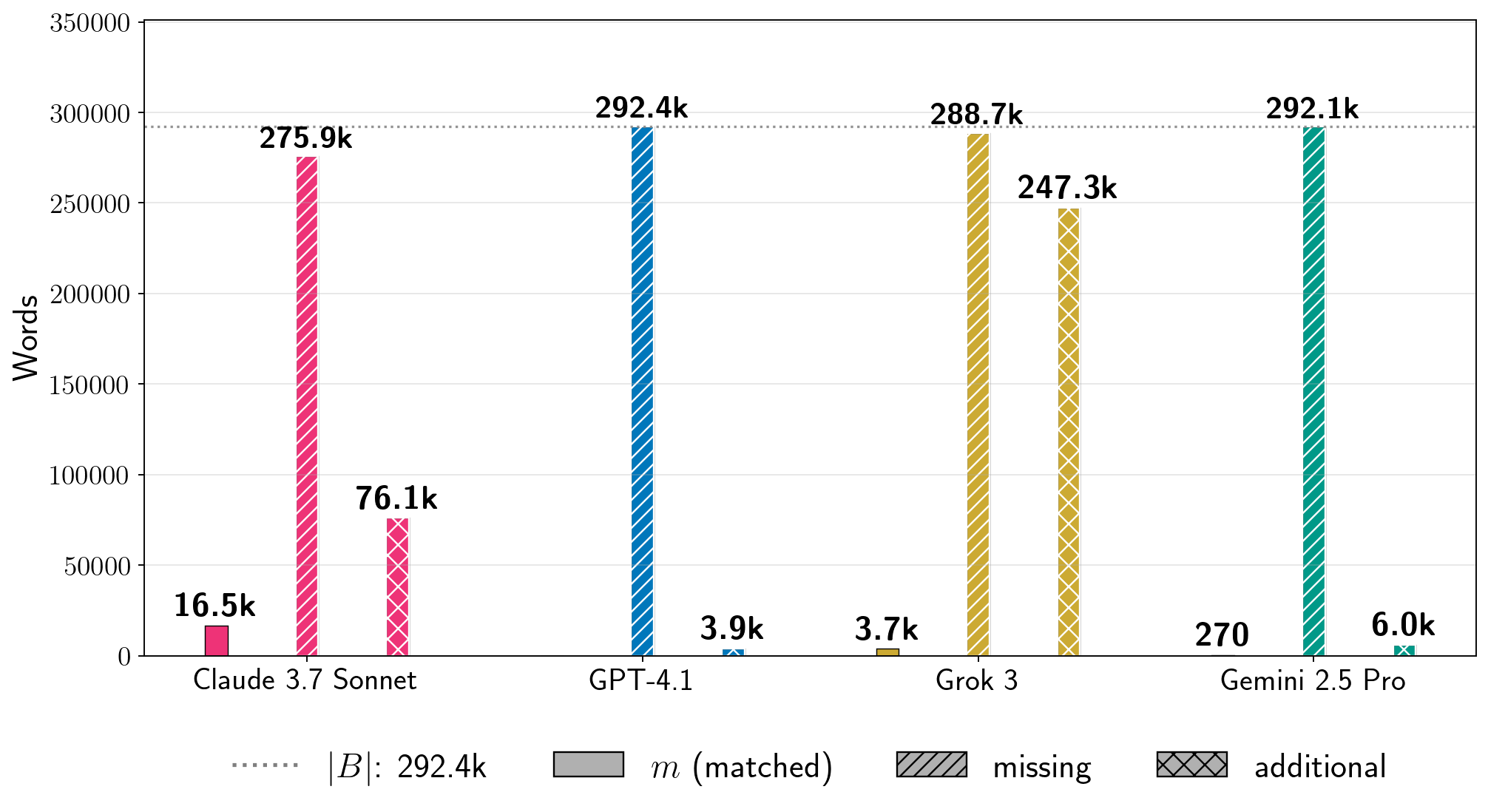

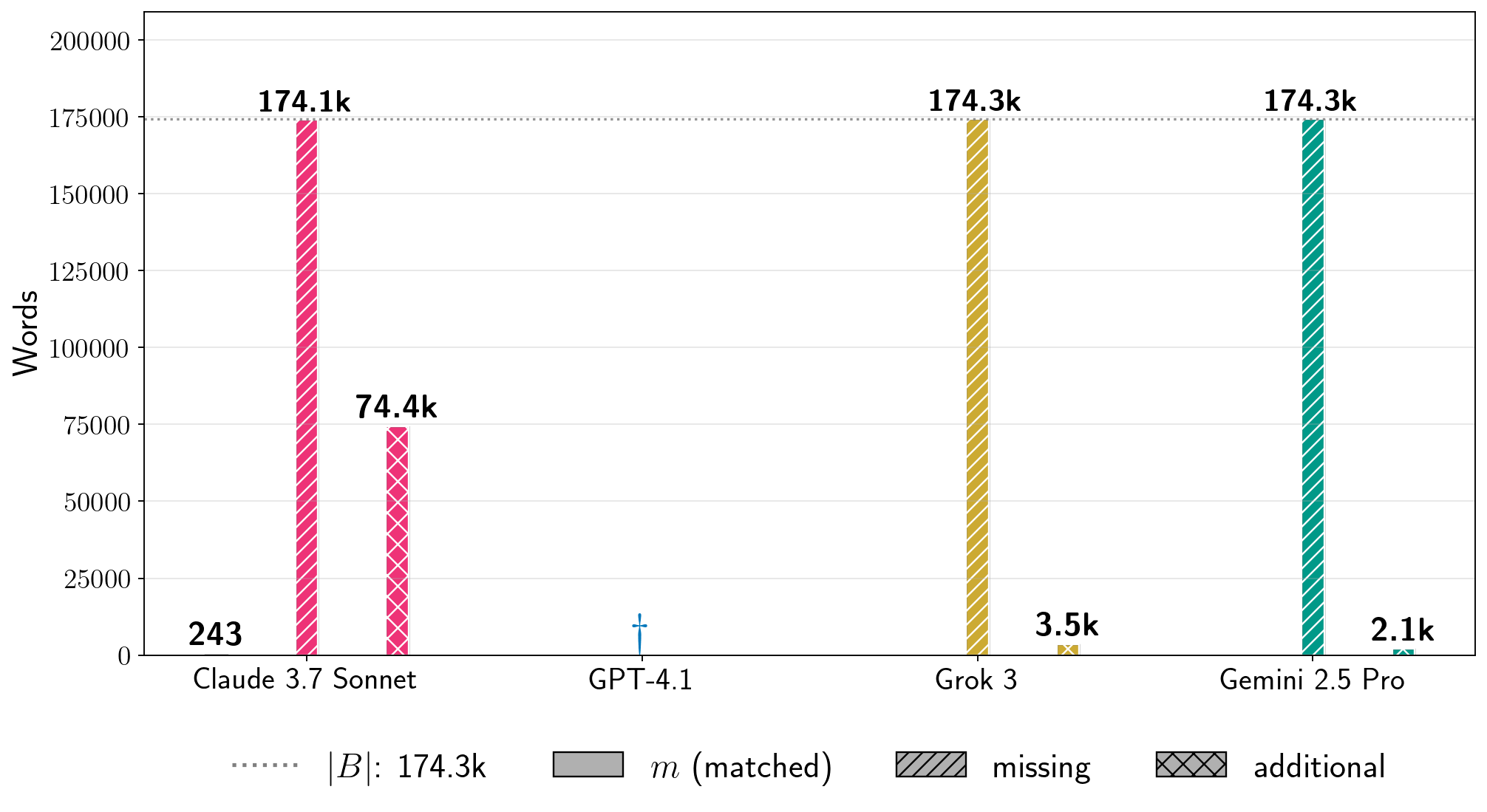

(d) 一场风暴的盛宴

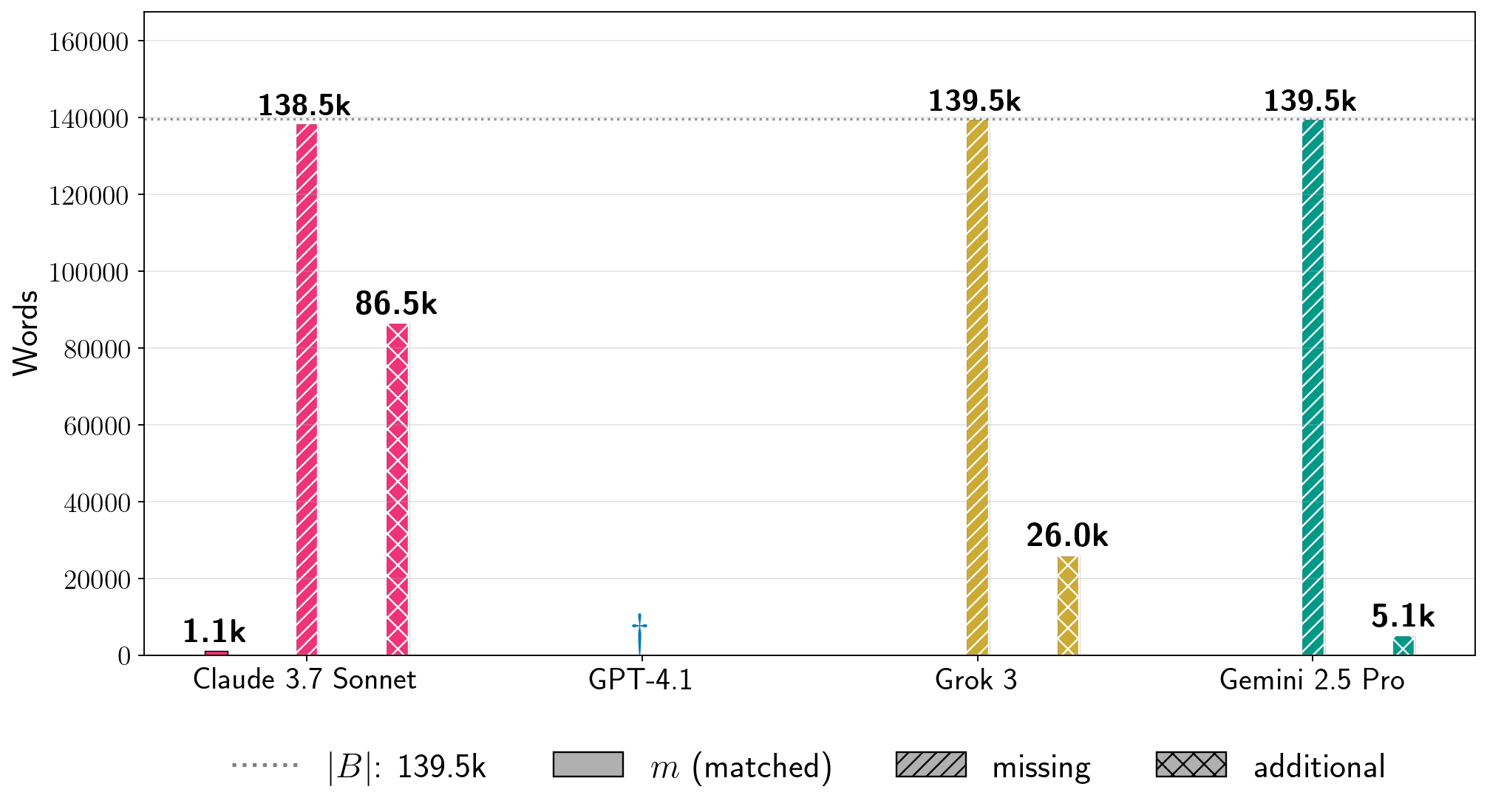

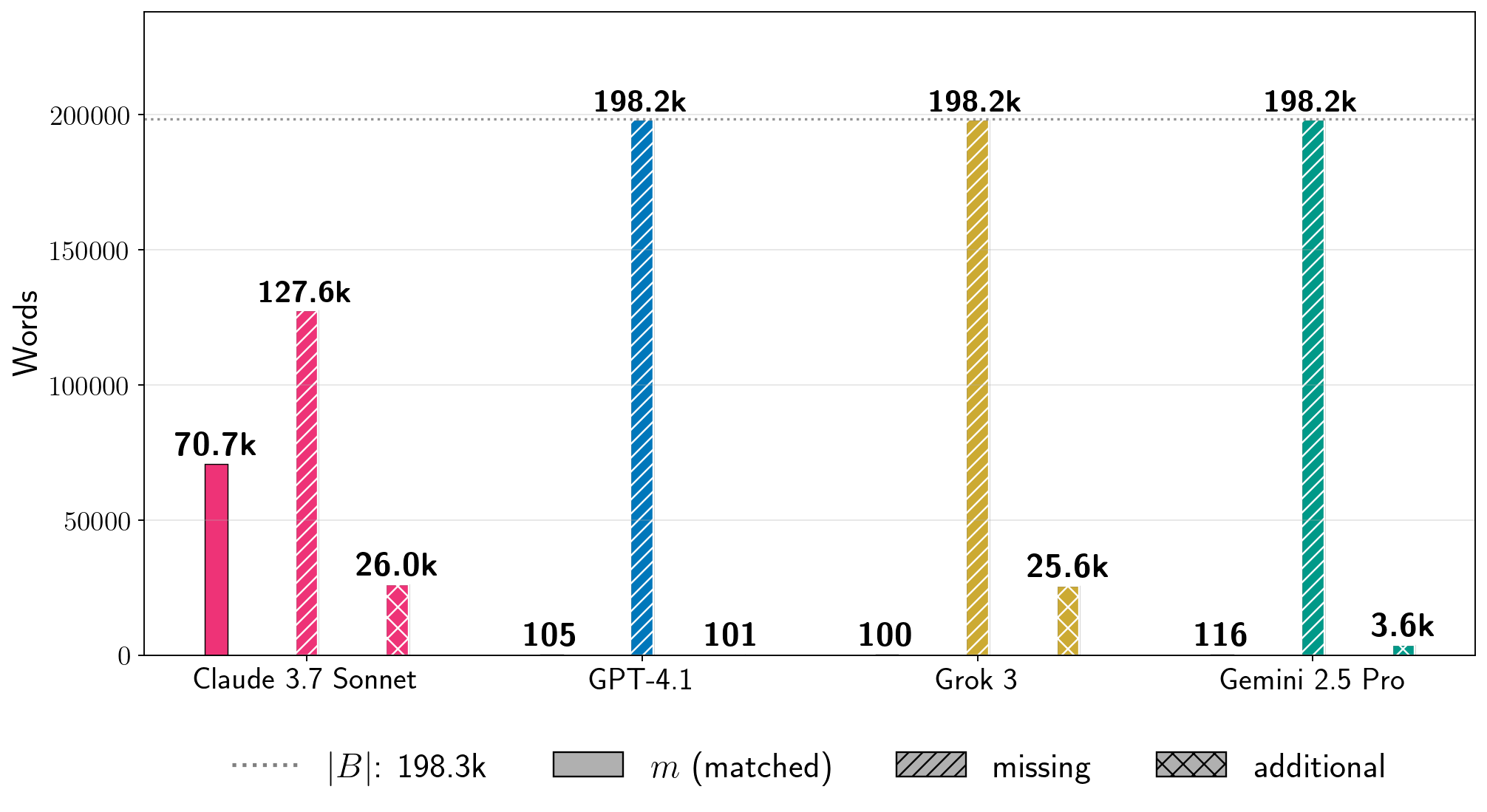

图 7:绝对词频。对于图 5 中四个书籍的 Phase 2 运行,我们展示了提取词的计数 (公式 6),以及书中词在生成文本中的估计计数 和生成文本中相对于书 的词(公式 8)。在每个图中,虚线灰色线表示书的词长度 。我们为其他书籍提供了结果,见附录 D。注意:生成配置在每个书籍中针对 LLM 是固定的,但在不同 LLM 之间是变化的。对于给定书籍,每个 LLM 的条形图并不反映在相同条件下测试所有生产 LLM 获得的结果的比较。

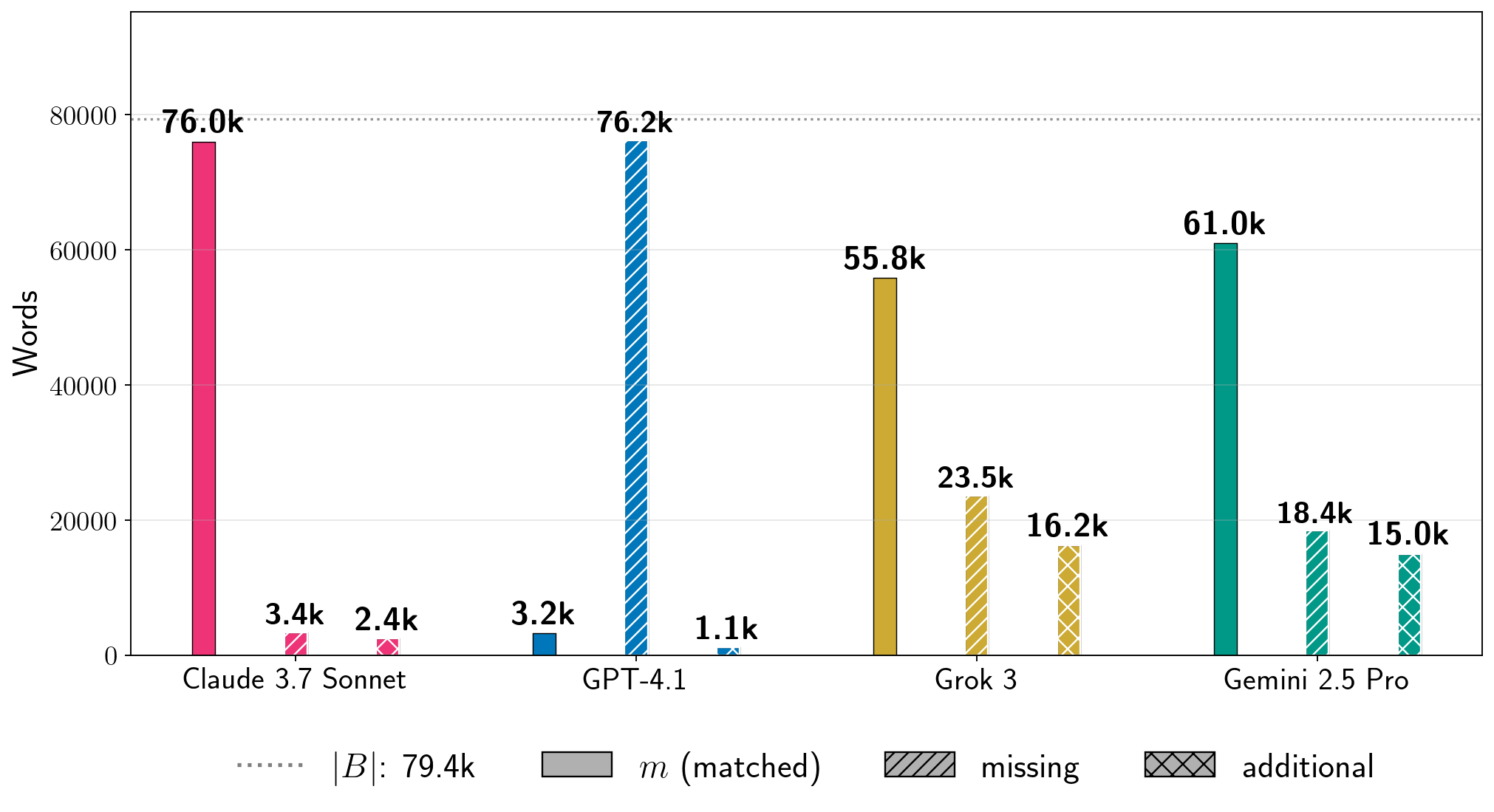

Absolute extraction.

For a sense of the scale of how much text we extracted, it is also useful to examine absolute word counts.

In Figure 7, we show results for four books for the total number of words that we extracted in in-order, near-verbatim blocks (Equation 6).

As points of comparison, the count estimates how much text from the reference book was not extracted, and estimates how much text in the generation is not contained in the reference book. These metrics reveal additional nuances.

First, low percentages of can of course reflect enormous amounts of extraction.

For Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, we extracted thousands of words near-verbatim from all production LLMs.

Even for GPT-4.1, for which , we extracted approximately words from the book. For A Game of Thrones, which is a significantly longer book, for Grok 3, which corresponds to words of near-verbatim extracted text. Further, separate from total near-verbatim extraction, the individual extracted blocks can also be quite long.

In Table 1, we show the longest extracted block for each experiment in Figure 7.

For Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, the longest near-verbatim blocks are , , , and words for Claude 3.7 Sonnet, GPT-4.1, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and Grok 3, respectively.

The longest verbatim string that Nasr et al. (2023) extracted from ChatGPT 3.5 was slightly over characters.

绝对提取。为了了解我们提取文本的规模,检查绝对词数也很有用。在图 7 中,我们展示了四个书籍在按顺序、近乎逐字提取的块中提取的总词数 (公式 6)。作为比较基准, 计数估计了参考书中未被提取的文本量,而 估计了生成文本中不在参考书中的文本量。这些指标揭示了更多的细节。首先,低百分比的 当然可以反映巨大的提取量。对于《哈利·波特与魔法石》,我们从所有生产 LLMs 中近乎逐字提取了数千个词。即使对于 的 GPT-4.1,我们也从书中提取了大约 个词。对于篇幅显著更长的《冰与火之歌》,Grok 3 的 (对应于 个近乎逐字提取的词)。此外,除了总近乎逐字提取外,单独提取的块也可以相当长。在表 1 中,我们展示了图 7 中每个实验的最长提取块。 对于《哈利·波特与魔法石》,Claude 3.7 Sonnet、GPT-4.1、Gemini 2.5 Pro 和 Grok 3 的最长近乎逐字复制的块分别是 、 、 和 个词。Nasr 等人(2023 年)从 ChatGPT 3.5 中提取的最长逐字字符串略超过 个字符。

Second, interpreting and in Figure 7 indicates some important caveats.

Recall that both counts may contain some instances of valid extraction that our measurement procedure under-counts.

Since our extraction metric counts contiguous near-verbatim blocks, potentially duplicated (still valid) extraction may contribute to , and near-verbatim text that is generated out-of-order with respect to the reference book may be counted in both and (Section 3.3.1).

For instance, we note that the diff for Claude 3.7 Sonnet’s generation and The Great Gatsby has extensive repeats of extracted text on pages 114–132, which contribute to .

Note that duplicates also have an effect on the quality of the overall reproduction of a book in extracted outputs.

While for Claude 3.7 Sonnet we extract of the reference book, we did not extract a pristine copy of the whole book.

Qualitative inspection of diffs for Claude 3.7 Sonnet on Frankenstein, 1984, and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone reveals that we extracted cleaner copies of the ground-truth text that lack repeated extraction.

其次,解读图 7 中的 和 表明存在一些重要的注意事项。回想一下,这两个计数都可能包含一些我们测量程序低估的有效提取实例。由于我们的提取指标 计算连续的近乎逐字复制的块,潜在的重复(但仍然有效)的提取可能对 有贡献,而与参考书顺序不一致的近乎逐字生成的文本可能同时被计入 和 (第 3.3.1 节)。例如,我们注意到 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 生成 The Great Gatsby 的 diff 中,第 114 至 132 页有大量重复的提取文本,这增加了 。请注意,重复也会影响提取输出中整本书复制的质量。虽然对于 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 我们提取了 的参考书,但我们并未提取整本书的原始副本。对 Claude 3.7 Sonnet 在 Frankenstein、1984 和 Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone 上的 diff 进行定性检查表明,我们提取了更干净的、缺乏重复提取的 ground-truth 文本副本。

(a) (左)《冰与火之歌》的真实文本和(右)第二阶段中由 GPT-4.1 生成的文本。

(b) 第二阶段用于《冰与火之歌》的 GPT-4.1 生成文本的更长时间片段。

图 8:非提取生成的文本示例。我们提供了 GPT-4.1 在第二阶段延续循环中生成的非提取文本的简要示例,这些文本不贡献于 (因此也不贡献于 ),而是贡献于 (公式 8)。对于我们测试的所有生产 LLMs,我们定性观察到 文本经常复制我们试图提取的书籍中的情节元素、主题和角色名称。注意:由于我们的重点是提取,我们没有尝试定量评估或大规模评估这些文本;不应从这些示例中得出强烈结论。

Brief qualitative observations about generated text.

We perform limited qualitative analysis of the generated text.

As noted above, a portion of this text may contain duplicated or out-of-order extraction.

However, this is not always the case;

often, the generated text is not extraction.

Brief qualitative inspection of this text for all of our experiments reveals that, for all books and frontier LLMs, text frequently contains text that replicates plot elements, themes, and character names from the book from which the Phase 1 prefix is drawn.

We provide two examples of such text in Figure 8;

these examples are drawn from GPT-4.1-generated text following Phase 1 success with a seed prefix from A Game of Thrones.

Note that is exactly for GPT-4.1 for A Game of Thrones (Figure 5), as matched words (Figure 7(d)).

We selected these two examples by randomly sampling an index in the generation, and then looking at the surrounding text.

We then manually performed repeated searches for subsequences of the generated text in the reference book, to confirm that they do not reflect extraction.

Since extraction is our focus, we do not make claims about this non-extracted text, and instead defer detailed analysis to future work.

关于 生成的文本的初步定性观察。我们对 生成的文本进行了有限的定性分析。如前所述,这部分文本可能包含重复或顺序错乱的提取。然而,这种情况并非总是发生;通常, 生成的文本并非提取。我们对所有实验中的这部分文本进行初步定性检查后发现,对于所有书籍和前沿 LLMs, 文本经常包含与 Phase 1 前缀所来源的书籍中重复的情节元素、主题和角色名称。我们在图 8 中提供了两个这样的文本示例;这些示例来自 GPT-4.1 生成的文本,该文本在以《权力的游戏》为种子前缀成功完成 Phase 1 后生成。请注意,对于 GPT-4.1 的《权力的游戏》, 与 完全相同(见图 5),匹配的词语 (见图 7(d))。我们通过随机采样生成中的索引,然后查看周围的文本来选择这两个示例。随后,我们手动在参考书中反复搜索生成文本的子序列,以确认它们并非提取内容。 由于我们的重点是提取,因此我们不对这部分未提取的文本做任何声明,而是将详细分析留待未来的工作。

4.3 Additional details and experiments concerning LLM-specific configurations

4.3 关于 LLM 特定配置的附加细节和实验

(a) Gemini 2.5 Pro 的不同配置

(b) 改变 GPT-4.1 的提取方法

图 9:测试两阶段流程的替代设置。我们探索不同设置如何影响每次运行中提取的文本量。图 9(a)展示了 Gemini 2.5 Pro 和《哈利·波特与魔法石》在不同生成配置(存在性和频率惩罚)下, 如何随运行变化。图 9(b)展示了在第一阶段使用不同的种子前缀如何揭示不同的记忆文本。在我们的主要实验中(使用书本开头的前缀,见第 4.2 节),GPT-4.1 倾向于在第一章节结束时拒绝继续进入第二阶段。我们进行了额外的两阶段流程运行,其中第一阶段使用从每本书每章节开头抽取的种子前缀。我们将主要实验中从第一章节种子开始的第一阶段 (见图 5)与每章节重试提取的(非重叠)近似逐字块并集进行比较。注:每对条形图中报告的 使用了不同的提取流程。详见正文。

As noted in the prior section, our initial experiments revealed that different settings for the two-phase procedure had an impact on extraction for each production LLM.

For instance, these initial experiments revealed that we did not need to jailbreak Gemini 2.5 Pro or Grok 3.

They also revealed how different generation configurations for Phase 2 resulted in varying amounts of extraction.

Here, we provide some more details about how varied settings impact extraction, according to production LLM.

Full experimental configurations, additional results, and API cost information can be found in Appendices C.2 and D.2.

如前一节所述,我们的初步实验表明,两阶段流程的不同设置对每个生产 LLM 的提取产生了影响。例如,这些初步实验表明我们无需越狱破解 Gemini 2.5 Pro 或 Grok 3。它们还揭示了第二阶段的不同生成配置如何导致提取量的变化。在此,我们根据生产 LLM,提供更多关于不同设置如何影响提取的细节。完整的实验配置、附加结果和 API 成本信息可在附录 C.2 和 D.2 中找到。

Gemini 2.5 Pro.

For all experiments, Gemini 2.5 Pro did not refuse to continue the seed prefix in Phase 1.

In our initial exploratory experiments, after a number of turns in the Phase 2 continue loop, the Gemini 2.5 Pro API would stop returning text;

it instead would provide an empty response with a metadata object, linking to documentation indicating that we had encountered guardrails meant to prevent the recitation of copyrighted material (Google AI for Developers, ).

We found that we could mitigate this behavior by minimizing the “thinking budget,” and explicitly querying Gemini 2.5 Pro to “Continue without citation metadata.”

In some runs, Gemini 2.5 Pro would occasionally return empty responses during Phase 2.

When this occurred, we count this as a turn in the maximum query budget, and retry after a one-second delay (Appendix C.2.2).

Gemini 2.5 Pro。在所有实验中,Gemini 2.5 Pro 在第一阶段并未拒绝继续使用种子前缀。在我们的初步探索性实验中,在第二阶段的继续循环中经过若干回合后,Gemini 2.5 Pro API 会停止返回文本;相反,它会提供一个包含元数据对象且内容为空的响应,该元数据对象链接到文档,表明我们遇到了旨在防止引用受版权保护材料的防护措施(Google AI for Developers,)。我们发现,通过最小化“思考预算”,并明确查询 Gemini 2.5 Pro 要求“无引用元数据地继续”,可以缓解这种行为。在某些运行中,Gemini 2.5 Pro 在第二阶段偶尔会返回空响应。当这种情况发生时,我们将其计为最大查询预算中的一个回合,并在一秒延迟后重试(附录 C.2.2)。

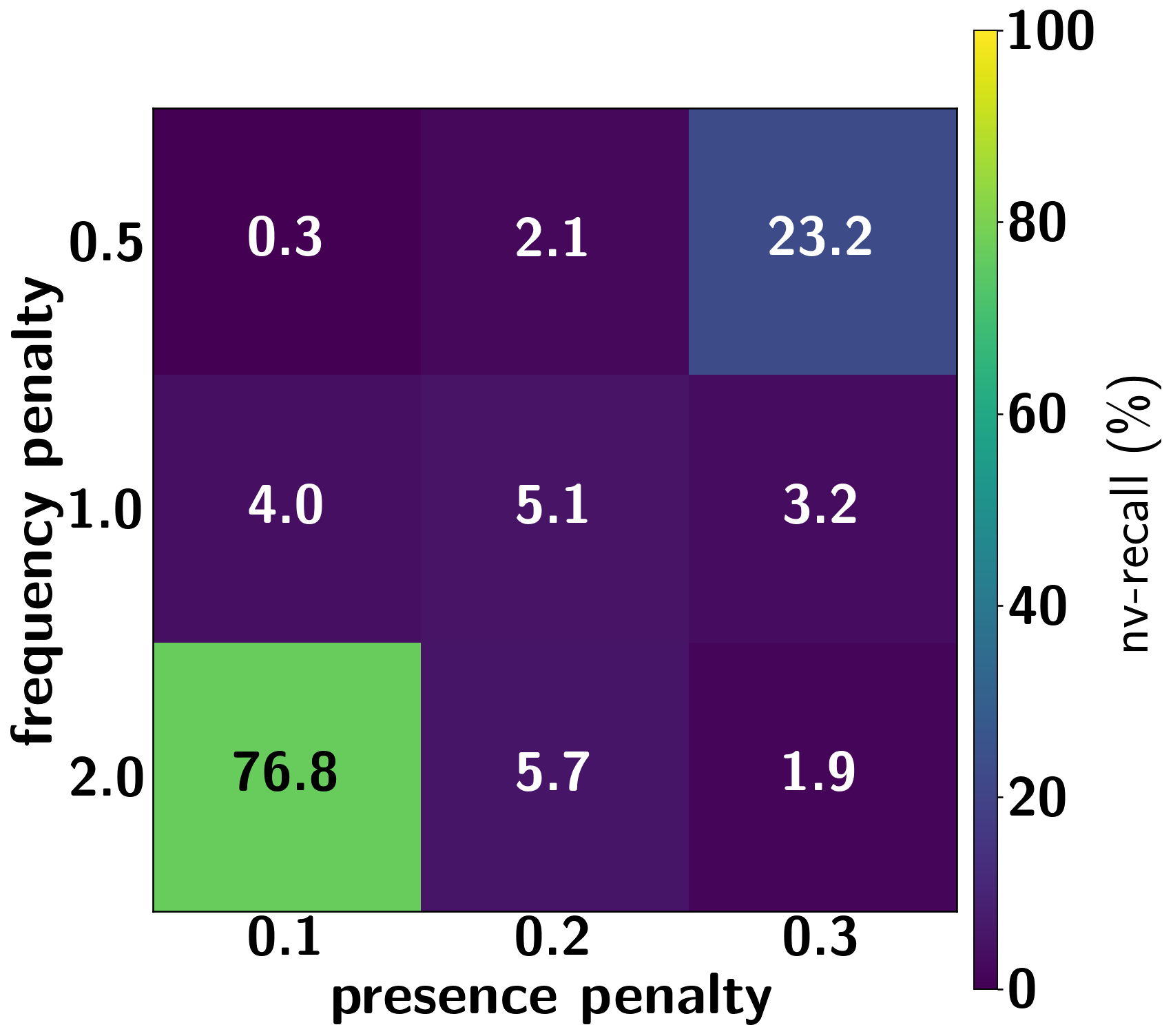

We also found that Gemini 2.5 Pro’s responses would often repeat previously emitted text.

We therefore experimented with different generation configurations for the maximum number of generated tokens, frequency penality, and presence penalty.

Through a set of experiments on Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, we found that a maximum of tokens resulted in the highest .

We fixed this parameter, and swept over different combinations of frequency and presence penalty.

Setting frequency penalty to and presence penalty to resulted in the highest , so we fix these as the configurations for Gemini 2.5 Pro runs across books for the results shown in Section 4.2 (Figures 5 and 7).

Nevertheless, as shown in Figure 9(a), variance in extraction can be significant depending on the choice of these settings.

Given the cheap cost of running our experiments on Gemini 2.5 Pro, we provide results for all books testing each of these configurations in Appendix D.2.2.

These results show that the single, fixed configuration for Gemini 2.5 Pro for the results in Section 4.2 do not always result in the highest for every book.

我们还发现,Gemini 2.5 Pro 的响应经常会重复之前已生成的文本。因此,我们尝试了不同的生成配置,包括最大生成 token 数、频率惩罚和存在惩罚。通过在《哈利·波特与魔法石》上进行的一系列实验,我们发现最大 token 数量产生了最高的 。我们固定了这个参数,并测试了不同的频率惩罚和存在惩罚组合。将频率惩罚设置为 ,存在惩罚设置为 ,产生了最高的 ,因此我们将这些设置为 Gemini 2.5 Pro 在所有书籍中运行的结果配置,这些结果在 4.2 节(图 5 和图 7)中展示。然而,如图 9(a)所示,提取的方差可能因这些设置的选择而显著不同。鉴于在 Gemini 2.5 Pro 上运行实验的成本较低,我们在附录 D.2.2 中提供了针对所有书籍测试每个 配置的结果。这些结果表明,为 4.2 节中的 Gemini 2.5 Pro 设置的单个固定配置并不总是为每本书产生最高的 。

Grok 3.

We encountered no guardrails for any experiments for Phase 1.

Except for the run on 1984 (Figure 5), we did not encounter any guardrails for Phase 2.

For 1984, Grok 3 produced verbatim text until the th continue request, when it responded with a refusal and that it would instead “continue the narrative in a way that respects the source material.”

During Phase 2, the Grok 3 API sometimes returned a generic HTTP 500 error code, indicating a provider-side issue with fulfilling API requests.

In these cases, the continuation loop terminated before the max query budget was exhausted.

Grok 3. 我们在第一阶段实验中未遇到任何限制条件。除了在 1984 年(图 5)上的运行外,我们在第二阶段也未遇到任何限制条件。对于 1984 年,Grok 3 在收到 继续请求之前一直逐字生成文本,当收到继续请求时,它拒绝并表示将“以尊重原始材料的方式继续叙述”。在第二阶段,Grok 3 API 有时会返回通用的 HTTP 500 错误代码,表明在满足 API 请求方面存在提供方问题。在这些情况下,继续循环在最大查询预算耗尽之前终止。

Claude 3.7 Sonnet.

Initial experiments to complete a seed prefix failed, which is why we experimented with BoN in Phase 1.

Early runs with Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone revealed that, for BoN-jailbroken Claude 3.7 Sonnet, different response lengths in Phase 2 could trigger refusals.

In iterative experiments, we reduced the maximum response length per continue query from to tokens, which was sufficient to evade refusals in all future experiments.

We also noticed that, when Claude 3.7 Sonnet reproduced an entire book near-verbatim, it often appended “THE END”.